When a sailboat suffers a heart attack

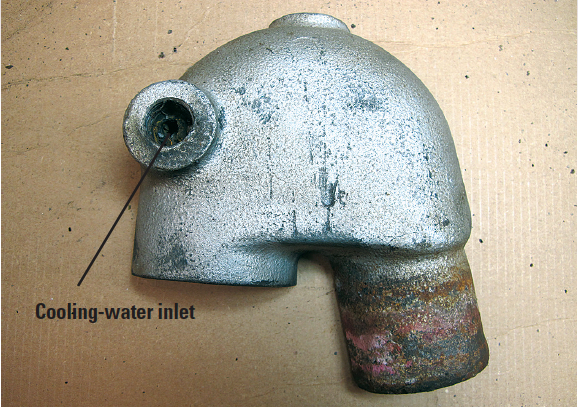

Pictured above, a mixing elbow connects to the exhaust manifold on the engine. Since it’s impossible to see inside it, the only way to inspect for blockages is to take it off completely.

It’s 0700 on a beautiful April morning in France. Entr’acte, our Nor’Sea 27, is on the River Seine in 18 knots of wind with 4-foot seas dead astern. We are facing upriver into an opposing 4-knot current. The engine has suddenly stopped dead. Smoke is coming through the engine- room vents along with the definite smell of something burning. All of this is accompanied by the shriek of engine-overheat- and low-oil-pressure alarms. Added to that is a constant stream of AIS danger-proximity alarms going off as fast as we silence them. This is a scene right out of a movie: the airliner is going down fast with alarms going off all at once. The pilot’s yelling, “Shut off those alarms! I can’t think!” But this is no movie. It’s my voice yelling, “Shut off the GPS and AIS! I can’t think!”

The silence was deafening. Entr’acte had just departed the lovely harbor of Honfleur, bound up the Seine for Rouen and onward to Paris and the French canals. We hadn’t a care in the world . . . until that moment.

We had planned most carefully. To prepare the engine, we reset the valves, rebuilt the water pump, and installed a new thermostat, a new impeller, new hose clamps, and all new engine belts. The engine had been meticulously maintained and had been running perfectly. Yet there we sat. What was going on?

A finely timed trip

The Seine is a powerful river with treacherous currents and is not to be trifled with. It is a major shipping artery, and pleasure craft are allowed to operate solely in the hours between one half-hour after sunrise and one half-hour before sunset. They are not permitted to anchor at all. Even if anchoring were permitted, outside the channel is a deadly maze of underwater anti-erosion dykes, rocks, and reefs. The result of all these restrictions is that we had to make the 60-mile trip from Honfleur to Rouen in one daylight run. This is difficult but, with the proper planning, not impossible.

That particular Sunday morning promised the perfect combination of good weather, low water just after sunrise, and current change one hour later. Sunrise was at 0530, and the plan was to enter the lock at 0545 and exit it at 0600, one hour before low water, with just enough water under the keel (we hoped) to gain the main channel. The first hour, bucking the 4-knot current until the time of current change, would be slow, but that was unavoid- able as we would need every minute of inflowing tide to carry us all the way to Rouen by sunset.

Our plan unfolded perfectly. Exiting the lock was a bit tense. Would we hit bottom outside the lock? We kept the engine rpm to 2,200 in case we touched. We had sent Entr’acte’s mast and rig on ahead to the Mediterranean and without it, her motion was dreadful, but three minutes later we turned upriver, entered the traffic pattern, and all was well.

At 0610 with wind and seas finally astern, we breathed easier and radioed Port Control for clearance to Rouen.

“Bonne journée, Entr’acte. Please keep to the port side of the river.”

The current seemed to stop us dead as we made an agonizingly slow 2 knots over the bottom, but in an hour it would change and the 10-knot sleigh ride to Rouen would begin.

The best laid plans . . .

I increased the throttle from 2,400 to 3,100 rpm, the engine responding beautifully as always, and off we went. As the control tower very, very slowly slid astern, we shouted, “We made it! Perfect timing! Are we good?”

Ten minutes later Ellen said, “I smell something burning.” We decided the smell was coming from the ship loading grain at the pier off to starboard.

Suddenly, I stopped smiling. The engine sounded fine, but there was an extra sound, something I could not pin down. I went down into the cabin to listen more closely, and as I turned around to tell her so . . .

WHHHRRrummff!!!!! In less than two seconds, the engine went from a solid, healthy 3,100 rpm to stone cold dead. Silence! That is, until all the alarms went off.

Without mast and sails, Entr’acte was helpless. The dinghy and outboard were no match for this current and sea. Besides, there was no time to set that up. There was a constant parade of 1,000-foot container ships moving in both directions as well as a working dredge just ahead. We were in the way big time!

In 35 years of boating, we had never felt the need to call for assistance, but this was our day. This was no time for pride, heroics, or hesitation. I radioed to Port Control that we were without engine and requested assistance.

Aside from the shipping traffic, we were safe enough. The smoke had stopped and we were not on fire. Entr’acte behaved beautifully. The wind against current balanced each other perfectly, allowing us to keep her head into the current and steer to the very edge of the channel and to maintain a predictable position while the current and slowly set us back toward the lock. For the moment it appeared that it could be a very short tow, but once the current changed we would be unceremoniously swept upriver out of control.

King Neptune was kind. Members of the local chapter of Les Sauveteurs en Mer — a French volunteer organization dedicated to the rescue of mariners and vessels in distress — just happened to be inside the lock servicing their boat. The lock doors opened and out came Les Sauveteurs to perform the fastest, most seamanlike “snatch and grab” we have ever seen. By 0720, Entr’acte was once again safely tied up in Honfleur and, after coffee and croissants with the crew of the towboat, we set to work.

Searching for the cause

Entr’acte’s Yanmar 2GM20 had performed flawlessly for 18 years and 3,500 hours without so much as a burp or hesitation of any kind. It had also been assiduously maintained since its installation.

Ellen was convinced that she already knew the cause of the problem, but a few simple checks were in order first.

I began by checking the prop. There was no large plastic bag to disentangle, as I had hoped. Besides, what of the smoke and smell? Next, I turned the engine over carefully by hand. It turned very easily, each cylinder coming up nicely on compression, indicating no water in the cylinders, no blown head gasket, and no broken valves.

I checked the oil for water contamination. It was the same beautiful amber color it had been two days before when I changed the oil. I hit the starter, voilà! She started right up . . . but did not sound right. No cooling water was being discharged with the exhaust.

I looked at Ellen in the galley. Before I could say anything profound she bent down, rummaged around for a moment, and — from the galley, mind you — produced a shiny brand-new exhaust mixing elbow and said, “Maybe you should install this!”

A water-cooled diesel engine has a mixing elbow. Its shape and config- uration varies depending on engine type, but it is there and is a critical part of the engine’s exhaust system. Most boat owners are not aware that they have one, and many confuse it with the water-lift muffler that is mounted low down, usually aft of the engine.

On Entr’act’s Yanmar, the mixing elbow is a large casting bolted to the side of the engine just below the cylinder head. The large rubber exhaust hose that leads from the engine to the muffler begins at the elbow.

Hot exhaust gases exit the engine through the exhaust manifold. For these gases to be conducted through the boat to the customary exhaust discharge at the stern, they must be cooled. This is done with the raw water used to cool the engine.

The Yanmar elbow is a casting built with two internal passages, a large one for the exhaust gases and a smaller one for water. After passing through the heat exchanger, the cooling water is injected into the elbow, where it mixes with exhaust gases and cools them to an acceptable temperature. The mixture then passes through the muffler and on to the overboard discharge. It’s a very simple process.

The water passage inside the new mixing elbow is clearly visible. It’s the smaller hole.

A potential trouble spot

The manual for the Yanmar 2GM20 specifies checking this elbow after every 500 hours of operation and changing it “if necessary.” This is important because a clear exit route for the exhaust gases is essential for any engine to perform well. All hot-rodders know that a large clean exhaust pipe means more power and a restricted exhaust pipe means less power. They spend inordinate amounts of time, energy, and money to have the largest, cleanest (on the inside) exhaust systems possible.

Since one byproduct of diesel exhaust is soot (carbon), this goal is difficult to achieve on a diesel engine. Over time, deposits build up inside the elbow and gradually reduce the diam- eter of the exhaust, degrading perfor- mance. When the engine is running, the exhaust and water are mixed inside the arteries of the exhaust elbow and passed on. After shutdown, the residual heat from the engine dries out the mois- ture and leaves behind solid carbon that dries to a very hard “plaque,” especially around the turn of the elbow, where it cannot be seen during a cursory inspec- tion. Likewise, inside the water passage, the liquid water evaporates and leaves behind solid salt, minerals, and rust. As the engine hours accumulate, so do these deposits. Eventually, the engine becomes more difficult to start, and for the lucky sailor, it will refuse to start before he leaves the dock, as opposed to suddenly shutting down at a critical moment . . . say, in the middle of the River Seine.

The exhaust inlet on the old elbow was clogged with rust and carbon deposits.

We have changed this elbow twice over the years. This new one would be our third replacement. We purchased it in advance specifically for this canal trip. Since the engine was starting and running so well, however, while it was on the to-do list, it was not at the top.

It took only 10 minutes to remove the old elbow and it was immediately apparent that Entr’acte had suffered a massive heart attack. Don’t laugh, that is exactly what it was. I looked down into the elbow and could see no opening of any kind. Nothing! Both “arteries” — the exhaust and the water passages — were completely occluded by a large clot of rust.

As I removed the clot, I could see that the insides of both passages were almost completely blocked with carbon, rust, and salt buildup. This was a perfect example of a massive “myo-exhaustical infarction.” The engine had appeared to function normally at regular rpm day after day, just like the guy who appears to be in perfect health under normal conditions until the day he runs to catch the bus and dies of a heart attack.

When the rust clot lining the elbow broke away, it completely blocked the passages for both the water and the exhaust gases.

The trigger

Even though our engine appeared to be functioning normally, we had planned to replace the elbow in Le Havre before the start of our canal trip. However, because of rainy weather we put it off until Honfleur. Then, with the prospect of perfect conditions on that Sunday, we decided to put it off until “tomorrow in Rouen” — one day too long!

While we were departing the lock at 2,200 rpm, all was well, but when we increased the rpm to 3,100 and “ran for the bus,” the engine suddenly began to force much higher volumes of exhaust gas and water into the almost completely blocked passages. This created what is called back pressure. If this pressure builds and has no place to go, eventually something has to give. In our case the exhaust manifold gasket blew. The burning smell and smoke came from the exhaust gas blowing past the manifold gasket and filling the engine room with exhaust. This was the sound that caught my attention. The death blow came when a rust clot, dislodged by the sudden acceleration, completely sealed the exhaust port, triggering the shutdown. The engine suffocated on its own exhaust.

Ed removed the debris for show and tell.

Telltale signs

There are symptoms of a blocked elbow. The aforementioned hard starting/non-starting is one, although our engine started easily and ran like a clock. There was, however, one symptom we did notice but misread: smoke. On the short trip from Le Havre to Honfleur, we commented that our exhaust was making quite a bit of white smoke . . . but we dismissed this as condensation. After eight years in tropical climates, we had forgotten what sailing in cold weather was like and, since April on the English Channel is very cold, we wrote off the smoke to condensation. How wrong we were.

The color of exhaust smoke tells a great deal. Normal exhaust is colorless transparent gas and water vapor and is practically invisible. Black smoke results from incomplete combustion or a low operating temperature producing carbon inside the engine and exhaust. Blue smoke means the engine is burning oil. White smoke is usually unburned fuel, but water vapor condensing in the air as it exits the exhaust indicates insufficient cooling water in the exhaust. A large amount of white exhaust is a warning that should be investigated.

When discussing the presence of white smoke, had we looked closely at the exhaust discharge, we would have noticed that it was discharging nowhere near the amount of water that we normally see and we would have discovered the problem in time.

The water inlet on the mixing elbow was almost completely clogged.

A passage resumed

With the new elbow installed, our engine started easily and ran smoothly, and the exhaust discharge contained a very healthy amount of water. We had to wait in Honfleur another 10 days for that perfect combination of conditions to reoccur, but the trip to Rouen was extremely pleasant and without incident. From Rouen to Paris, however, was another matter altogether, and that is the subject of an article that will appear in a future issue. We weren’t quite done with the side effects of our engine’s heart attack.

Mixing-elbow maintenance

The best way to avoid the conditions that result in a clogged mixing elbow is to treat your engine well.

A diesel needs to be run under load, but not under excessive load. Do not run your engine in neutral for long periods, such as at anchor to charge batteries or run a watermaker. This accelerates carbon buildup inside the engine. If you must perform these functions at anchor, engage reverse gear and run the engine at medium rpm, and try not to do it too often or for too long.

Splitting the elbow revealed the extent of the blockages.

Run your engine hard and in gear for at least 20 minutes every time you run it, preferably just before shutdown.

Make certain that your propeller is properly sized. A too-large prop will overload an engine, and that will lead to increased carbon buildup inside the engine and the exhaust.

Tune in to the sight and sound of your engine’s exhaust. What sounds normal? How much water discharge do you normally see? Watch for smoke. Quantity and color are dead giveaways.

Examine the mixing elbow at the required intervals or, preferably, more frequently. If you see a buildup of deposits, you might be able to chip out some of it near the opening, but this will be only a short-term solution as the innermost parts of the elbow will be inaccessible, especially in the water passage. I have not found a chemical capable of satisfactorily dissolving these deposits. In most cases it will be easier to replace the elbow than to clean it.

When replacing the elbow, you may have to heat the joint to break it free. Do not get overly enthusiastic lest you crack the manifold. It may be necessary to cut off the old elbow with a grinder, but be careful not to damage the threads of the union or the manifold itself where the elbow is attached.

Materials and tools:

-

New exhaust manifold gasket. These can never be reused. Carry one or two as spares.

-

New mixing elbow.

-

Threaded union (if your engine has one) that joins the elbow to the manifold.

-

High-temperature thread sealant.

-

Large securely mounted vise.

-

Large pipe wrench with a 2- to 3-foot piece of pipe to use as a lever. (Be gentle!)

-

Butane torch in case the wrench and lever are not enough.

- High-speed grinder for severe cases. Be careful not to ruin the threads on the union if you have one.