I love my new-to-me 1999 Beneteau 311, but the boat came with a very pronounced smell in the head, which persisted despite my best efforts to clean and sanitize. The 19-year-old marine sanitation hoses were permeating black water Beneteau resulted in effluent sitting in 8 feet of sanitation hose that connected the holding tank to the through-hull discharge valve, as there was no shut-off valve at the bottom of the elevated holding tank.

The system provided two options to move the waste, one directly into the holding tank and the other overboard. But the Y-valve configuration meant that to use the overboard option, the entire contents of the holding tank went with it. It would have been handy to have a valve on the holding tank discharge to prevent the tank from emptying but still be able to discharge overboard where that option was available.

The smell and the corresponding problems, including blockages, leaks, and seeping joker valves, meant that the whole system was in need of replumbing. But replumbing wouldn’t relieve me of the unpleasant notion that I would often be sailing around with a tank of raw sewage. All of this motivated me to consider alternatives to the conventional marine head/holding tank solution.

Options

I started researching the possibilities: cassette toilets, the Electro Scan system, and composting toilets.

A cassette toilet—the Thetford Porta Potti, for instance— is a Type III marine sanitation device (MSD) that’s portable and incorporates a holding tank. Typically, the holding tank section of a cassette head separates from the seat and freshwater reservoir to facilitate disposal into a shoreside toilet. The system requires using strong chemicals in the portable holding tank to break down solids and control odors.

I’d used a cassette toilet in my Seaward 24 and it worked fine. But dumping and washing out the holding tank was never a pleasant task. While the cost of this sanitation solution was low, and the whole system was small and self-contained, I had no desire to revisit the chemical smell and the dumping process aboard my Beneteau.

Next, I considered a Type I MSD, that is, one that includes an on-board treatment system. This solution treats waste downstream from a conventional marine toilet, and that treated waste is deemed safe for legal discharge, eliminating the need for a holding tank. Raritan’s Electro Scan is a popular example and the one I considered.

Using the Electro Scan, after each flush the waste (black water) enters the first of two chambers. Here, a macerator turns the waste into a liquid with suspended fine particles. Then electrodes in the chamber send electricity through the liquid. The current reacts with the saltwater to neutralize and disinfect the waste. When the head is next flushed, the treated waste liquid moves into the second compartment where the process is repeated. But this time, before it’s electrified, the liquid is mixed rather than macerated. The next time the toilet is used, the first batch of twice-treated sewage is discharged overboard from the second compartment. The cycle repeats with every flush, and the system’s capacity is huge; over 500 gallons can be treated per day.

As fantastic as the Electro Scan sounds, there are issues to consider. The Electro Scan system requires saltwater for flushing. Brackish or freshwater doesn’t permit the necessary conductivity. I could install an optional salt-feed system, but this would increase the complexity and add points of failure. Also, the system cannot be used in a no discharge zone (NDZ), of which there are many; the Environmental Protection Agency maintains a list of all NDZs in the United States. I called the Coast Guard and asked if, when they boarded a boat in an NDZ, they checked for proof that a Type I MSD was not in use; they confirmed they did.

Another issue with this system is its demand for electricity. The 12-volt system’s macerator is rated at 20 amps, the electrodes 25 amps, and the mixer 5 amps. Raritan reports consumption of 1.2 amp-hour per flush. The cost is less than I expected, with units starting at around $1,200. But given that I often sail in brackish water and in NDZs, the Electro Scan wouldn’t work for me.

Finally, I took a good look at a composting toilet. I learned that the secret of composting toilets is that they are designed to keep liquids and solids separate. The liquid is emptied at regular intervals depending on usage, but much more often than the solids/compost storage area. Solids are mixed with a composting medium such as peat moss, coconut coir (husk), or a material such as aspen bedding used for keeping small animals. All absorb moisture, which is key.

I spent several days reading reviews of composting toilets written by real people, both boaters and recreational vehicle (RV) owners. I didn’t come across anyone who regretted trading a holding-tank system for a composting system.

Encouraged, I focused on learning more about the three brands competing in the marine and RV market: Nature’s Head, Air Head, and C-Head. All boast excellent reviews, but my overriding consideration was size. The cockpit protrudes about 8 inches into the top back wall of the head compartment aboard my Beneteau, making sitting up straight on a taller head impossible.

I quickly determined that the Nature’s Head and Air Head were too tall, at 21 inches and 19.75 inches, respectively. Only 15 inches tall, the C-Head’s Shorty model would fit better.

Installation

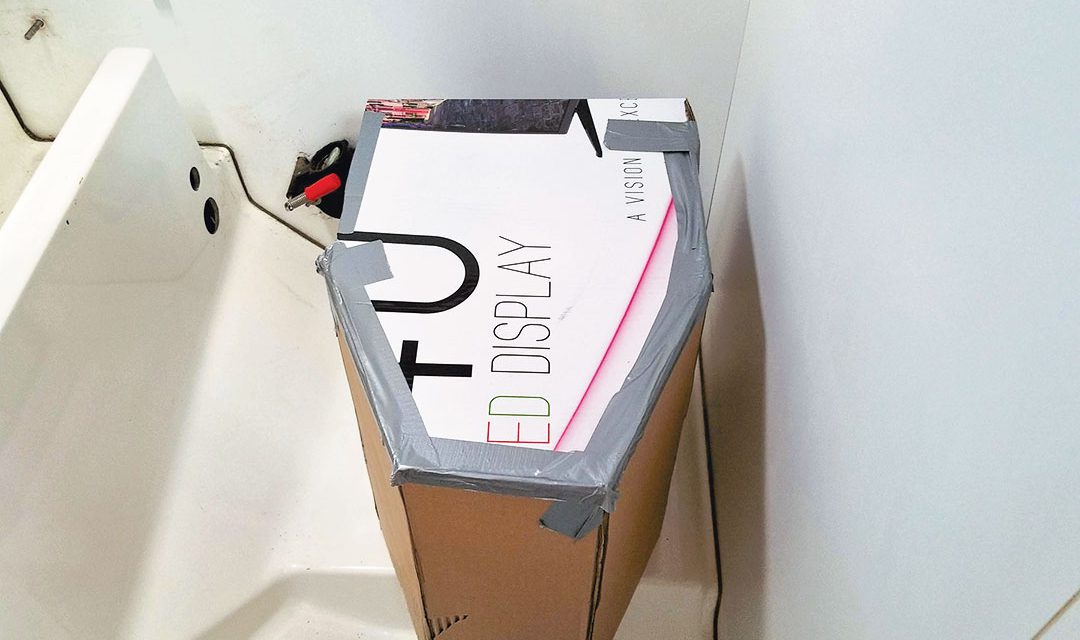

To make sure the unit would fit, I created a cardboard mock-up using instructions from the C-Head website. But to test the mock-up, I’d be going all in anyway; the entire system already in my boat would have to go.

To prepare for removing the system, I pumped out the holding tank, ran about 3 gallons of bleach water (5 parts water to 1 part bleach) through the head and into the holding tank, and then pumped out again. Finally, I opened the discharge seacock and pumped fresh water through the system. My careful prep meant no nasty surprises when I removed the marine head, holding tank, and sanitation hoses. As soon as they were out, I could see the first benefit of not having a holding tank—a new large storage area.

Before proceeding, I thoroughly cleaned the compartment. Next, I positioned the C-Head mock-up where the real one would live. Satisfied it would work, I mixed thickened epoxy to fill the holes in the shelf where the old toilet had been mounted. Next, I positioned the new C-Head and sat on it to determine the perfect spot. I marked the locations of the mounting bolts and drilled four 3⁄16-inch pilot holes into the shelf. Then I fixed the C-Head to the shelf using four 1⁄4 x 1-inch galvanized screws with washers, first wrapping the washers in butyl tape. Installation done!

I’d read about ventilation requirements for composting toilets and called the C-Head distributor to ask about this. He told me that in heavy-use installations, such as multiple liveaboards, a 12-volt fan helps prevent condensation that would impede the composting process. This is important because moisture is the enemy and the cause of foul odors. He advised me to first give my composting head a try without any active or passive ventilation; as it turns out, I’ve not needed ventilation with my system.

Operation

To prepare the head for use I added composting medium to the solids container. I chose aspen bedding because it was available at the local Tractor Supply store. Next, I filled and stowed 2 1⁄2-gallon sealable plastic bags with pre-measured amounts of bedding for future use.

Using the head is simple. Unlike a traditional toilet bowl, the composting head bowl is divided and shaped to move liquids and solids into separate areas. After depositing solids, which fall to that compartment, you simply close the lid, insert a handle into the socket at the top, and turn the handle to stir the deposited solids with the bedding.

Number one requires a little more precision, since the primary goal is to never let liquids and solids mix. This means that men have to sit down to urinate (something women have no issue with, though some men find it awkward). The urine enters a reservoir under the seat, which is nothing more than a gallon milk jug to which I add a 50-50 solution of vinegar and water to control odor.

Although the C-Head can compost toilet paper, I have tried it with and without, and I believe it works better when there’s no paper in the mix. It doesn’t seem to break down as well as the solids. Rather than depositing toilet paper into the head, I keep sealable plastic bags under the sink for used paper, which then go into the trash. (I know this is a common practice among people who use traditional marine toilets anyway, since paper can easily clog those systems if overused.)

Emptying the solids is easy. I bring a trash bag into the head, remove the solids bucket, place the trash bag over the top and turn the bucket over. I refill with fresh aspen bedding material and I’m done. The whole process takes about five minutes. I can legally place the trash bag of composting waste in a dumpster—far better and more sanitary than the millions of Pampers that are tossed daily.

As for capacity, I generally singlehand, and I haven’t come close to capacity using the boat for 20 days. I will empty after around 20 “deposits” just because it is easy to do.

Emptying liquids is a matter of sealing the milk jug and dumping the contents in a shoreside toilet or, if offshore beyond three miles, overboard. For longer trips, I bring extra jugs with lids so I can cap and store them until I can properly dispose of them.

I’ve had no odor issues with this head. One problem I did have, briefly, was of my own doing: I left the boat for a month and failed to empty the solids container before leaving. When I returned there was no odor, but there were fruit flies (lots of them) in the head. Apparently, they entered via a hole in the handle socket. Now when I leave the boat for an extended period, I empty the solids reservoir and I leave the handle in place to close the socket.

I have been using the C-head composting toilet for over two years, and I am very pleased with it. I still appreciate opening the door to the head and not being assaulted by stinky smells. And, I was able to permanently eliminate two below-the-waterline holes in my boat that served the old marine toilet, one for the saltwater intake for flushing and one for the waste discharge.

What do I miss about my old conventional marine head? Not one thing.

A Misnomer—Editors

According to composting expert and author of The Humanure Handbook, Joe Jenkins, there is no such thing as a composting toilet. According to information on his website, humanurehandbook.com, “Toilets don’t compost, people do. A ‘compost toilet’ collects organic material for composting elsewhere.”

The site goes on to say, “Composting, by definition, has three requirements: 1) human management; 2) aerobic conditions; and 3) the generation of internal biological heat. If these three requirements are not met, composting is not taking place and the end result should not be called compost. Most devices referred to as ‘composting toilets’ do not produce compost and should be referred to as dry toilets or biological toilets, anything but composting toilets.”

Composting takes a lot of time, and aboard a boat the organic, compostable waste is intended to be emptied and discarded before it’s actually composted. Of course, this doesn’t negate any of the very real benefits; we just want to be precise.