The challenges and rewards of 48 days sailing the Florida Keys

Issue 152: Sept/Oct 2023

It took hours to rig, pack, and launch the boat. We suffered in the heat and humidity, sweating through our too-heavy northern clothes. Finally, we motored out to raise the sails, only to realize that the centerboard was stuck. We had to get it down before we could sail, otherwise this was going to be a very short cruise. I swam under the boat, wrapped myself around the 400-pound keel, braced against the hull, and tried tugging it down. No luck. Back aboard, I tried hammering it down through the cockpit scupper.

Giving up, we motored back to the launch ramp, put the boat on the trailer, and bounced it up and down the rough incline until the keel fell. On the water again, we sailed north in a dying breeze as the sun set, finally cooling off and starting to enjoy life.

We anchored near the north shore of Florida’s Blackwater Sound, dropped our sails, and were instantly savaged by hordes of ravening mosquitoes. So much for our dreams of sleeping under the stars out in the cockpit. By the time we’d made it below we were blotched and swollen from dozens of bites and spent the next hour swatting the mosquitoes trapped in the cabin with us.

What the heck were we doing here? Twenty-odd years prior, my wife, Heidi, and I built a straw-bale cottage in Washington’s Selkirk Mountains and have lived there happily ever since. We have a trickle of electricity from solar panels and no indoor plumbing, and the long, dark winters can bring as much as 10 feet of snow. So perhaps it is understandable why one day last winter Heidi said, “I’d like to spend next winter on a sailboat somewhere warm.”

Magic words! But where and what boat? Lake Powell, straddling the border between Utah and Arizona, would be great, only it’s dried up. The Sea of Cortez might do, but we don’t speak Spanish and weren’t sure it was entirely safe. The Bahamas is fantastic, but we’re not ready to cross the Gulf Stream. That left Florida.

Loaded up and rolling south with Intrepid in tow and the canoe on the roof.

Now for a boat. We’re somewhat new to sailing, starting in 2016 when I built a little flatiron skiff. Bitten by the boat- building bug, I’d followed with a bigger skiff, then a 15-foot cat yawl with a cabin, and most recently, an outrigger canoe. The cat yawl comes close and would do for one person, but not a couple.

Given one summer to build a suitable boat, what would you choose? I decided the Wharram Tiki 21 was ideal, but the wife insisted she would not “sleep in a torpedo.” We considered renting a boat until I learned how expensive that was. Next idea was to buy a cheap boat off Craigslist in Florida, fly down, and live aboard while fixing her up. We called this the “Captain Ron Option.”

Instead, we decided to buy a boat and fix it up at home. I started hunting for an old fiberglass trailer-sailer, the biggest that I could tow cross-country behind our 16-year-old Jeep. I found plenty of backyard wrecks on broken-down trailers, but most were far too heavy.

Then along came a 44-year-old San Juan 21 MKII. It was not on my preferred list, but it was light enough, so I emailed the owner, then noticed the ad dated from 2015. Surely it was long gone. Amazingly, I got a reply. It was in their barn, and we could see her when the snow melted.

Heidi took an instant liking to it (this is the most important factor when buying a boat), so we sold our tractor and paid them $3,500.

The boat was ready to sail, but we spent all summer turning the spartan racer into a comfortable cruiser. I cut away part of a quarter berth for more legroom and space to stow a portable toilet under the cockpit. Next came insulating and lining the cabin with cedar, then installing a galley counter with a two-burner stove. To finish off the interior, I made a medicine cabinet, storage lockers, and shelves of all kinds while Heidi reupholstered cushions and sewed hanging pouches.

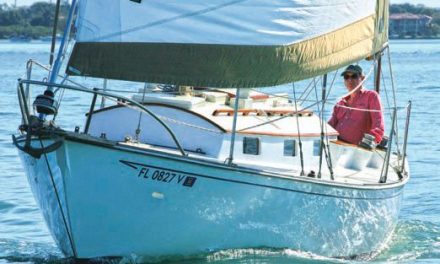

The first day on the water in the Florida Keys, and Heidi is all smiles.

Outside I added toerails, replaced the companionway slider with doors, made stern rails of galvanized pipe, and made two anchor roller platforms. Last, we sewed two lines of reef points into the mainsail. The work seemed endless, but if we were going to live in a space the size of a refrigerator box, it had better be a nice refrigerator box. Finally, we painted on her new name, Intrepid.

Now it was time to learn how to sail the boat. I knew nothing of sloops and was aghast at all the ropes and wires. We were able to spend five nights aboard that fall on Lake Roosevelt, where we learned the basics before it started snowing. We left in early December and took our time going south.

I’d found a marina near Key Largo on Blackwater Sound that would store our car and trailer for two months for $550, and we launched Intrepid on Dec. 21. The first day had been hectic and the night muggy, so we started the second day with a relaxing swim to cool down. Heidi jumped in first, and standing on deck, I saw a plume of silt as something big swam out from under the boat. Not just big — it was almost as long as our canoe! I thought something was about to eat my wife for breakfast, then noticed how slowly it was moving and the horizontal tail. Belatedly, I realized it was a manatee, huge but lazy, and a herbivore. Phew! Welcome to the Florida Keys, I thought.

We took life easy, swimming and canoeing, resting up from the long drive, and acclimating to the unaccustomed heat and humidity. The next day a short, violent squall hit while we were having lunch, and we dragged anchor. Then a cold, wild northerly passed through, and we spent two days tied to the mangroves to keep from blowing away. The wind howled in the rigging and the mast vibrated, shaking the whole boat. We wore down jackets and huddled below by the propane heater wondering if we’d lose the mast. Christmas dinner featured Spam.

Heidi warms her hands by the propane heater on Christmas Day.

Despite squally weather, we sailed back to the marina on Dec. 26 to resupply. This was the first time we’d ever reefed the mainsail, and it was good to see how handy the SJ 21 is as we scooted along on all points under just a reefed main. As we approached the marina, five dolphins frolicked around and escorted us in while people on the docks took pictures.

Upon our return to the marina, we realized that we’d been pretty ignorant about the whole venture and quickly learned a few key lessons: Storing a vehicle at a marina doesn’t mean you can leave your boat tied to the dock there all day while you go to town.

Marinas in the Keys charge by the length of the boat and the towed dinghy. At the local rate of $4 per foot, it would cost us $150 to tie our boat and canoe up for the night, so we never did.

Like many naive Northerners, we had visions of palm trees and endless sandy beaches. Why not? I grew up on Long Island and now sail on Lake Roosevelt, and both have many perfect sandy beaches. Instead, we found endless sulfur-smelling mangroves. In the Keys, you pay to visit the best beaches and most of the others are private or have signs posted saying, “Protected Area, No Landing, Wading or Shell Collecting.” Also, January is the windiest month of the year down there, and if you can’t happily sail in 20-plus knots of wind, you’ll spend much of your time at anchor.

Along with lessons learned, we made all the noob mistakes: Lost the end of the halyard and watched it zip up the mast. Raised the jib upside down. Dragged improperly set anchors. Raised the tiller to open the lazarette, then lowered the tiller against the open lid, neatly prying the rudder off the pintles while sailing briskly along. Our canoe got away from us, and I had to swim for it. The second time we sailed in high winds, we ripped a line of reef points out of the mainsail. But we never made the same mistake twice and noticed we were usually the only sailboat actually sailing.

The couple’s canoe served as a trusty tender for resupplying and exploring.

We used the motor sparingly, burning only two and a half gallons of gas in 48 days, preferring to move the sloop by sail, paddle, and kedge. This is partly because in the past, our $200 Chinese Hangkai 3.5-hp outboard has been singularly unreliable, and partly because it’s so noisy. On this voyage it always started, sputtered, and hiccupped right along. I love my Hangkai because it has made me a better sailor.

The Florida Keys are shallow, and running aground was common. Most cruisers didn’t dare leave the Intracoastal Waterway, but we sailed everywhere. I learned to sail with one hand on the tiller while swinging the boathook with the other to take soundings. Intrepid draws about 3.5 feet with the keel in the “mostly down” position and we often anchored in 45 inches, which is marked on the boathook as our minimum depth.

The first time we touched bottom was a panic party — drop sails, anchor, haul up the keel and rudder, start the motor. Soon it became routine. Heidi would hold on to the mast and rock the boat vigorously, stirring up clouds of mud as the keel swept side to side, which occasionally let us sail off. Often, she’d get into the canoe and just that much less weight would free us. Sometimes we’d paddle an anchor out and kedge off. As a last resort, we’d unbolt and crank up the keel. It helped that I was rereading The Riddle of the Sands by Erskine Childers at the time.

Friends encouraged us to cross the Gulf Stream or set a course for Dry Tortugas National Park. I listened to reports of 6-foot seas and said, “No thanks! Maybe in a few years when I know more about this game.” For now, we were content to stay in sheltered waters. As it was, we endured five wild northerlies and once saw the telltale streaks of a Force 7 wind form around us as we sailed along. This was exciting enough for us.

We intimately explored from Card Sound down to Plantation Key and into Florida Bay. It seemed we were the only cruisers to spend time in Long Sound and similar shallow places. We usually found more water than the charts indicated and had these areas all to ourselves, seeing only small fishing boats now and then.

Drying out bedding on Intrepid’s boom after a rainstorm.

Our goal was not some epic voyage, but simply to spend the winter on a sailboat someplace warm. We enjoyed sailing a nimble boat all over, explored at will, beachcombed, canoed, swam in secluded spots, and slept onboard in our cozy den instead of in some overpriced motel. Once every five to seven days, we’d grant ourselves “shore leave” not only to resupply and do laundry, but also to sightsee by car and buy a fancy meal.

Often, we swam or floated about the boat in the afternoon. Diving under the sloop to scrub its bottom became a game. We got good at it, had fun, and the hull stayed clean. After swimming we’d rinse off in the cockpit with a solar shower hanging from the boom. We carried 17 gallons of water in recycled plastic bottles. We washed our dishes one at a time over the side and gave them a skimpy freshwater rinse. Our electrical system was a folding solar panel and a few rechargeable lights.

Navigation in the Keys was simply, “Let’s go thataway.” We had a pocket weather radio, 30-year-old Kmart binoculars, a chartbook, a good lensatic compass, and a borrowed GPS we used only once to check our coordinates and four times to see how fast we were going for the fun of it. The one thing we lacked was a proper boom tent for shade. We improvised with a small tarp and umbrellas. I’ll make a good one before our next cruise.

We chose a canoe for a dingy because my wife hates rowing and would rather mess about in a canoe than most anything else, and the light canoe car-tops well. It was perfect for exploring and tows effortlessly, though it always swamps when towed downwind in anything but a gentle breeze.

We paddled endless shallows and tiny mangrove channels, drifting silently over manatee, rays, baby sharks, blue crabs, and all manner of fish. Its impressive turn of speed and effortless glide made paddling a couple of miles for resupply easy, so we could anchor away from marinas — good thing, since its length almost doubled what it would have cost us to stay at one. When we went ashore, we’d pick up the canoe and stash it behind a dumpster or along the wayside, and it was never disturbed.

The author peers through binoculars while sailing through the Keys.

All good things come to an end, and eventually we tired of too much sun and sultry nights trapped in the cabin by mosquitoes. and started to fondly remember the refreshing chill of the north. Then the worst storm we’d experienced hit with violently shifting Force 7 winds and torrential rains. We had to move anchorages several times during the storm and the normally dry cabin leaked, soaking our mattress. It had been an amazing adventure, but after 48 days on the water, we were done for now. The next day, we hauled the boat out and started on the long trail home. But we’ll be back. We’re hooked and are already planning our next voyage.

We snowshoed back to our home on Feb. 19. Inside it was 34 degrees. The cottage was spotlessly clean and seemed pleasantly spartan to me with its brick floor, whitewashed walls, and minimal furnishings. I built a roaring fire and went out to shovel off the porch and hack a trail through frozen drifts past the woodshed to the outhouse. While working, I paused and marveled at how bright and beautiful the snowy forest around us was, how fresh the clean, cold air was. I remembered how wonderful living here is, something I’d forgotten.

Over the next few days, I found myself enjoying little things like cooking standing up, drinking tea from a ceramic mug instead of plastic, and most of all, sleeping in our own bed and staying in one place for a while.

I go sailing for the fun of it. It forces me to live in the moment and provides dynamic engagement with the real, natural world, which renews my interest in life. Equally important is coming home with fresh eyes and once again appreciating all that we have.

We can hardly wait to go cruising again.

Robert grew up on Long Island Sound, where he and a buddy sailed a Super Snark to destruction. Eventually he moved to the Pacific Northwest, where he canoed happily for decades. One day on Ross Lake in Washington state, he and his wife were hammering the water as if killing snakes, trying to round a point in a canoe in high wind and waves, when it occurred to him that it might be nice to once again have a boat that could harness the wind.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com