You may not be able to win the war, but you can win occasional battles. Regardless of the odds, you must fight! Now’s the time to meet your opponent.

It’s the ultimate mismatch: you versus an enemy infinite in numbers, awesome in reproductive power and blessed with all the time in the world.

In the Mildew Wars, eternal vigilance (and a bottomless bottle of bleach) is the price of freedom from odors, ineradicable black stains, allergies, and possibly even disease. You may not win, but the alternative to a ceaseless delaying action is to be driven from the water.

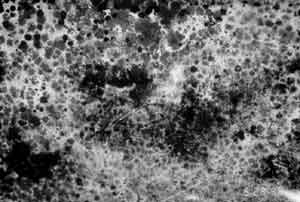

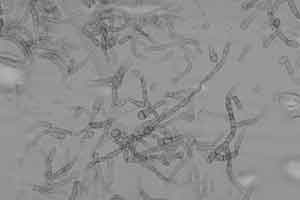

Up close and personal: a shot of a moldy wall in a home that experienced standing water for more than a month.

Behold the enemy

Mildew is the common name for several varieties of fungi, tiny organisms also known as mold. They reproduce by spores, an extremely efficient method of propagation. Some species can fling their mature spores several feet as a means of enhancing dispersal. And if they land on a spot not conducive to growth, the spores can lie dormant for years – even centuries – waiting for conditions to improve. And they can wait almost anywhere, remaining viable even when subjected to temperatures approaching absolute zero.

Mildew can eat almost anything, anywhere – preferably somewhere warm, dark, and damp. Like your boat. Mildew grows by sending out long cells that sprout additional side cells in an endlessly repeating cycle. Under ideal conditions, a single mildew cell can become a half mile of cells within 24 hours and up to 200 miles, yes two hundred miles, of densely packed, interlocking cellular growth in 48 hours. The mildew chains that can propagate in a warm, moist hanging locker during a couple months of storage are able to attain lengths approaching the astronomical.

Rather than engulfing and digesting their food like higher life forms, mildew excrete their digestive enzymes onto the food source (host), turning complex molecules such as insoluble starches into soluble low-molecular-weight compounds that can be absorbed directly through the cell walls.

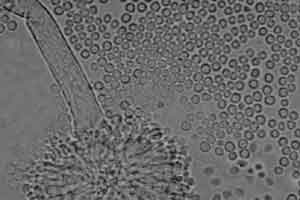

Aspergillus, a.k.a. common mildew: typically black, brown, gold, or bluegreen, mildew grows on damp surfaces and has a familiar “musty” odor.

The ravages of war

When something reproduces like mad and eats almost anything, it’s a serious enemy, even if it’s microbe-sized. It quickly becomes a visible mass and, in the case of mildew, a very unattractive one. The splotchy staining that appears on everything from portlights to leather to Dacron is a sort of spy plane view of a mildew forest – and of the damage it has done to the underlying surface, as you discover when you remove the mildew and part of the discoloration remains.

And then there’s that musty, unpleasant odor. That’s from the decomposition of whatever surface the invaders’ digestive enzymes destroyed as they were turning your boat into fungus food.

Molds are known to cause allergic reactions. However the greatest risk associated with mildew is the change that occurs to the host as a result of mildew digestion. As the enzymes convert the host surface to a soluble substance, the host is eroded and weakened. Fungicides, bleaches, and whiteners may return the surface to like-new appearance, but the appearance is deceiving. Even if it’s too slight to see with the naked eye, there is permanent pitting, which attracts dirt, grime, and new mildew infestations. At worst, the host may be so weakened that it will fail under high stress. Mildew-damaged sail stitching that lets go in a gust is one particularly notorious example.

But wait! Aren’t there mildew treatments, and mildew-resistant products on the market? Yep. But they only buy you time. The mildew-resistant treatment on fibers or hard goods loses its effectiveness in proportion to the conditions it confronts. In ideal growing conditions, its mildew-fighting ability is used up quickly. There is very little that is mildew-proof in this world. Ask anyone who has discovered that it has etched the lenses of his binoculars so badly that they are unusable. It won’t slow down for most paints or surface treatments and thrives on many. It does prefer natural plant- and/or animal-derived substances such as cotton, silk, leather, or wood, but can make do quite nicely on artificial surfaces like Biminis, sail covers, Formica, plastics, wiring insulation, or fiberglass, adhesives, lubricants, and sealants. About the only substances mildew can’t digest are metals.

The battlefield

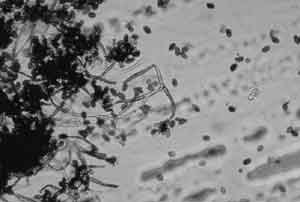

Stachybotrys, a mold with an extremely high moisture requirement (a cellulose digester which likes straw, hemp, jute, and sheetrock and looking like a greasy black growth)

Alternaria, a common carpet and wet windowsill mold with a high moisture requirement, looks black and fuzzy

Penicillium, another common mildew similar to Aspergillus with a similiar musty odor

Mildew prefers a sub-tropical climate – high humidity, warm temperatures (about 85° F is ideal), and still air. The still air helps maintain the moisture critical to its life processes. But it can adapt to much more extreme climates on both the high and low sides of the heat and humidity spectrum.

Though they can challenge us at any moment in any suitable setting, our fungalfoes are especially likely to attack on three vulnerable fronts:

- Winter or off-season storage. A sealed-up boat, summer or winter, is a sitting duck for a mildew onslaught. Just because it’s 15 degrees and a blizzard out doesn’t mean that mildew isn’t on the march in your sailbag. Its digestive and life processes generate heat. The bigger the colony grows, the more heat it produces. Mildew has been known to generate enough heat to produce spontaneous combustion in hay.

- Closed spaces and lockers. Boat designers enclose every available nook and cranny for storage. But every bulkhead, overhead, locker, drawer, and bag impedes air circulation, promotes condensation, and encourages heat buildup. Mildew doesn’t have to work nearly as hard to heat the few cubic inches of unoccupied air in a locker packed with stuff as it would several hundred cubic feet of open cabin, nor will its precious moisture evaporate as quickly. Not a big problem, perhaps, if your boat is an ultra-light racer with nothing much below decks but ribs and hull. But cruising in such Spartan surroundings wouldn’t appeal to most of us.

- The marine environment. Marine means wet, and not just the water upon which your good old boat is floating. There’s also condensation where the cool insides of the hull meet the warm, moisture-laden air in the cabin. Under the sole. Or behind the settee and cabinetry. Marine also means dripping packing glands, anti-siphon valves, and (to those of us who are truly cursed) an ice locker draining into the bilge. Water, water, everywhere . . . and all of it being used against you.

Fighting back

Most traditional remedies rely on sodium hypochlorite (household bleach) to remove mildew. You can add TSP (tri-sodium phosphate, available at most hardware stores) to the formula to make it more effective. A good, strong, all-around solution is four quarts of fresh water, one quart of bleach, 2/3 cup of TSP, and 1/3 cup of powdered laundry detergent. Do not use liquid detergents in combination with bleaches and TSP. Scrub the affected surfaces, using rubber gloves and eye protection. Rinse thoroughly.

Some caveats:

- Some fibers may be discolored by this treatment, especially animal fibers like leather, silk, and wool.

- If you rinse with salt water, finish with a fresh water rinsing. A salty surface attracts moisture and fungus ninjas.

- Never mix acids, rust removers, or ammonia with bleach while cleaning; poisonous fumes will result.

- Bleach may weaken some fabrics. If you are unsure about yours, try the solution on a small, hidden spot. Most commercial mildew removers also use sodium hypochlorite or near relatives. Follow the directions and warnings on their containers.

Pressure washers work with lightning speed but may force spores deeply into porous surfaces. I don’t recommend them for removing mildew.

Establishing détente

Your best strategy against the fungal foe is prevention, and low, dry heat may be the single best weapon. High heat is theoretically even better, since it is deadly to mildew. But it would be a Pyrrhic victory. You would have to keep your boat interior at 200° F plus to reliably destroy mildew – a heat level which would do more harm than the mildew. However, a low-temperature electric heater designed for marine use can do a great deal toward halting the mildew hordes. In combination with a fan, it safely reduces the humidity in a boat, even during the warm summer months. Such heaters are almost required equipment in the misty Pacific Northwest.

Dry is good. In fact, dry is best. Taking away moisture will stop most mildews from growing or reproducing. Open every possible airway, big and small, to enhance circulation. Install fans to keep air moving throughout the boat. See that lockers and companionway doors have as many louvers as possible. Bulkheads between staterooms can also be louvered. (How much privacy do you have on a boat, anyway?)

Even the head bulkheads can be louvered, with the louvers angled downward toward the head side to deflect shower water back in. Shutting down after the weekend or vacation should not mean buttoning your boat air-tight. Use Dorade vents or solar-powered vent fans, leave a porthole open in the head, and put louvers in the companionway drop boards.

Leave the sole boards and bilge inspection ports open while you’re away. For long-term idle periods (seasonal storage, etc.) bring your PFDs, cushions and bedding home to a nice dry attic. Look into professional sail storage, where sails are washed and dried, then hung, not folded, in order to avoid creasing.

Sunlight’s ultra-violet radiation can inhibit mildew. Airing gear, hard and soft, that can be brought topside provides the triple benefits of drying out, imparting a fresh smell and zapping the mildew with UV.

And while you’re doing that, a few hundred miles of the little monsters will be growing in some dark recess of your bilge.

Article from Good Old Boat magazine, May/June 1999.