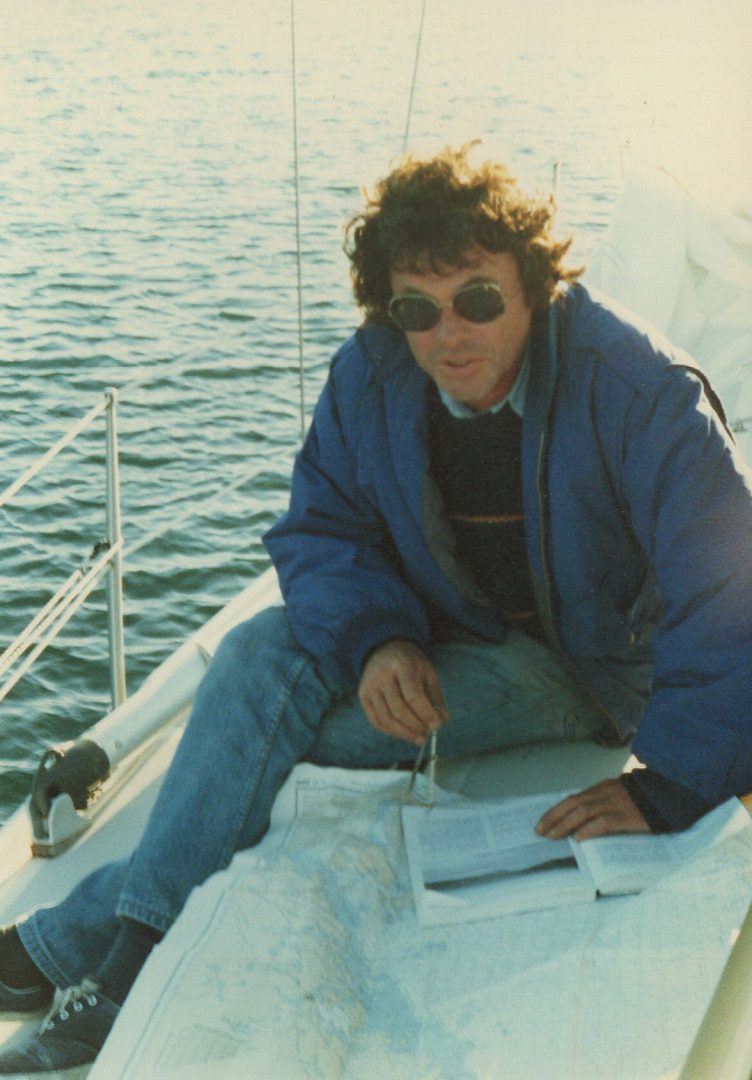

A lifetime’s love of sailing was inspired by a most inauspicious early voyage.

The curious thing is the way it creeps up on you. One day you’re asking the old salts at the club about replacing shaft bearings, dealing with loose-footed main sails, or installing lazy jacks, and suddenly, young sailors are asking you about these things, and you realize that somehow, without even noticing the passage of time, you’ve become one of them. An old salt.

The curious thing is the way it creeps up on you. One day you’re asking the old salts at the club about replacing shaft bearings, dealing with loose-footed main sails, or installing lazy jacks, and suddenly, young sailors are asking you about these things, and you realize that somehow, without even noticing the passage of time, you’ve become one of them. An old salt.

I came to sailing by pure serendipity in about 1984, in the days before furling headsails, GPS, and self-tailing winches. A film producer asked me to help him sail his new used boat some 100 miles across Georgian Bay in October to a winter yard. Because I’d written a script about a sailing adventure, he assumed I knew how to sail. Because he owned a boat, I assumed he knew how to sail. We were both mistaken. Neither of us knew much beyond the basics. And we had no idea of the perils of sailing on Georgian Bay in October.

The boat, a 31-foot Contest from Denmark, had been laid up for seven years. When the producer, whose name was Bill, and I arrived in Killarney, Ontario, to start our adventure, neither of us had ever seen the boat nor had any idea about its condition. The yard in Killarney had rigged the mast and bent on the sails. A contingent of headsails waited in the V-berth. There was a marine radio that neither of us knew how to use, dilapidated life jackets, expired flares, and a cantankerous Volvo diesel that didn’t like the chill in the air on that October day. In retrospect, things could have gone much worse than they did.

The batteries were dead, so we hand-cranked the Volvo for half an hour before it sputtered to life. Then we motored, oblivious, out of the harbor and into the vastness of Georgian Bay.

Without any discussion, Bill and I assumed roles. I raised the main and Bill handled the mainsheet. He also took charge of navigation and helming. I worked the foredeck, hanking on sails and trimming the jib sheets. With a brisk 20-knot breeze out of the west and a crisp, clear sunny day before us, we set out for Lonely Island, where we planned to moor that evening before pointing the bow for Meaford the next day. On the chart, I noted that Bill had drawn an impressively straight line from Killarney to Lonely Island, and the compass confirmed we were on the right heading. Both of us found navigating easy and sailing hadn’t proved difficult to master either.

Around noon, the wind eased and shifted to the south. I went below to find a bigger sail. I hauled a bag labeled “Drifter” topsides. After dropping the genoa, I began hanking on Drifter, having already cleated the starboard sheet in the cockpit to keep it from flapping around. With Bill at the helm, I started hauling on the halyard. Yard after yard of sail streamed from the sail bag. When the head of the sail finally reached the top of the mast, the wind picked up. The sail filled and the boat lurched, burying her lee rail. Chop that was now building sent sheets of spray everywhere. Bill clung to the cockpit coaming and I continued my desperate bear hug of the mast.

“Get that thing down!” Bill yelled, and I uncleated the halyard. But the wind had it now, and as soon as the boat started to right herself, it would fill again and toss us back to the precarious heel, and the water would again wash over us in sheets. I crawled hand-over-hand to the bow and began pulling the sail down the forestay. With the boat pitching and jumping in protest, and me straining and clinging to the pulpit, it was slow going. When I finally had Drifter down and back in the bag, I crawled to the cockpit. The gauge said we were doing 6.5 knots under just the main.

“Get that thing down!” Bill yelled, and I uncleated the halyard. But the wind had it now, and as soon as the boat started to right herself, it would fill again and toss us back to the precarious heel, and the water would again wash over us in sheets. I crawled hand-over-hand to the bow and began pulling the sail down the forestay. With the boat pitching and jumping in protest, and me straining and clinging to the pulpit, it was slow going. When I finally had Drifter down and back in the bag, I crawled to the cockpit. The gauge said we were doing 6.5 knots under just the main.

As I lay recuperating and contemplating putting up a smaller headsail, I sensed concern in Bill’s eyes. “What’s the problem?”

Bill’s voice was flat. “The good news is that with this wind we’re going faster than I thought we would.”

“And…”

“The bad news is we’re going in the wrong direction. The boat won’t keep on course for Lonely Island.”

We both looked at the chart and its straight line to Lonely Island. If we missed Lonely Island, we’d be sailing all night and come morning have no idea where we were. With a determination that belied the terror he was feeling, Bill took pencil, protractor, and compass to the soaking wet chart.

“We maintained our original course for 6 nautical miles, which put us here. Then we got knocked down to our current course for the past 3.5 miles, which puts us here. If we tack and go 7 miles the other way, and keep repeating that pattern, we should still reach Lonely Island some time tonight.”

I looked at him. “Do you really believe that?”

He smiled. “I will if you will.”

It was a magnificent plan, but once on the opposite tack, we found ourselves still sailing away from our destination. I put up a number three jib and took over the helm. Bill went below to work on the charting. At intervals he’d emerge and have me alter course or tack again. Then he’d disappear below and calculate some more. The afternoon light was fading. The only encouraging thing was the way the boat was handling. With the small jib and full main she was leaping along at 7 knots and riding as smooth as a Mercedes on the Autobahn.

Bill came up from below and worked his way forward. He held onto the forestay and scanned the horizon. The sun was low and in his eyes. He looked back at me on the helm and shrugged. We were lost.

After a while he made his way back to the cockpit and took the wheel. He had a new plan. We’d keep sailing until we sank or hit something. Under the circumstances, his approach seemed practical.

Day gave way to dusk, and a full moon rose above the horizon. We’d tacked twice and Bill thought we should be close, even if we couldn’t see anything. I went forward and peered across the water, and then for just a moment, when the boat sank into a deep trough, I saw it: a sliver of light between a speck in the water and the southern tip of what we knew was Manitoulin Island. That speck was it: our destination.

“There…there it is dead ahead…Lonely Island!” I shrieked, “Bill, you’re a friggin’ genius!”

We sailed to within a quarter mile of the island and dropped sail. Even though it was colder now than the morning, the Volvo started after only a few minutes of hand cranking. The chart showed shallow water at the mouth of the small cove on the island. I took bow watch, yelling instructions aft over the howling wind. The keel hit bottom once, bounced, and then we were into the sheltered cove. We motored to the lee of a berm at the western side of the bay and dropped the anchor. It was about 10 p.m. and we could hear the wind howling outside, but it was calm and safe in our little cove. Neither of us had eaten all day, and the steak and beer dinner we made remains one of the most delicious meals I’ve ever enjoyed.

We sailed to within a quarter mile of the island and dropped sail. Even though it was colder now than the morning, the Volvo started after only a few minutes of hand cranking. The chart showed shallow water at the mouth of the small cove on the island. I took bow watch, yelling instructions aft over the howling wind. The keel hit bottom once, bounced, and then we were into the sheltered cove. We motored to the lee of a berm at the western side of the bay and dropped the anchor. It was about 10 p.m. and we could hear the wind howling outside, but it was calm and safe in our little cove. Neither of us had eaten all day, and the steak and beer dinner we made remains one of the most delicious meals I’ve ever enjoyed.

We went to sleep well before midnight, under brilliant stars and a full moon. But at 5 a.m., I was up at the bow answering nature’s call and thinking, “I could walk down that anchor rode, it’s like a tightrope.” Looking astern, I realized we’d dragged our anchor across the cove and were about 20 feet from shore. I roused Bill and we anxiously cranked the Volvo to life as the boat edged ever closer to the pebbled shore.

Just as the sun peeked over the horizon, we bounced out of the cove and raised the main. With the wind still howling, that was all the sail we needed to maintain 6 knots. Far off in the distance we could make out a vast coastline, but just where Meaford was on that coastline, we weren’t sure.

We motorsailed because the engine was helping us to stay on our straight-line course to Meaford, and we hoped it would charge the batteries so we wouldn’t have to hand crank again. Of course, this meant that at the helm, dutifully staring down at the compass, I was engulfed in a cloud of diesel fumes. Within the first hour I lost the steak, beer, and my morning coffee over the rail to the choppy sea. Mid-morning, I hollered below to Bill, “What are all these islands?”

He came up immediately. “There are no islands.”

I pointed across the starboard bow. He looked worried and scrambled back below. Then he resurfaced, glancing between a chart and the islands.

“Must be Christian Island, it’s not supposed to be there,” he stuttered, “we must be too far south.”

“There’s more than one island, it looks like a chain,” I corrected him.

Bill studied some more. “That can’t be right. Maybe they’re the Strawberry Islands, but they’re way to the north, and we’re north of them, and we just left Lonely Island.”

I held the helm steady and spoke softly. “And that is a chart for Georgian Bay?”

“Of course it’s for Georgian Bay!”

We both stared at the islands in silence. Maybe we’d sailed into the Twilight Zone, or the Georgian Bay Triangle. Bill took a deep breath, “Just stay on course and let’s see what happens.”

Soon the wind shifted to northeast and we cut the engine and raised the jib. The boat sailed beautifully, and the wheel became a magic wand in my hand. She’d gradually creep up toward the wind after cresting a wave, and I’d make a slight correction. She’d respond and then try to go a bit more into the wind at the next wave. I’d correct again. The boat and I were getting along wonderfully. If only we knew where we were.

Bill brought the chart into the cockpit. “Have you noticed something?”

“What’s that?”

“We haven’t seen one other boat. We’re the only ones out here.”

I thought about that for a moment, feeling my gloved hands numb on the wheel, my down jacket a weak shield against the stiff, cold wind. “I think their boats are in harbor and they’re sitting before a warm fire.”

Bill nodded.

At that moment, I looked to starboard and realized the islands had disappeared. What we’d taken for islands were just the heavily forested heights of land between the low-lying pasturelands along the coastline that ran from Meaford to Tobermory. From a distance, the low areas were sunk below the horizon, appearing as water between the hills. There were no islands! We were on course! Then the thundering booms sounded.

“Rain coming?” I asked, looking around.

Still focused on the chart, Bill was jubilant.

“Wait, no…that’s the Canadian Forces artillery range!” He looked up and pointed. “It’s supposed to be right there, and it is! They’re firing artillery shells at us! Isn’t that great?” The markers in the water told us we were about 500 yards beyond the range of the guns, theoretically.

By early evening, we were within a mile of our destination. Following the shoreline for an hour, we’d lost our sense of fear and dread. We were close to land, but still we couldn’t see the harbor at Meaford. The entire shoreline was nothing but trees and rocks. Then I spotted a thin clear-cut against the background of dark green hills. Through binoculars, Bill saw cars driving.

“That’s it. That’s got to be the road into Meaford.”

We dropped sail and motored closer. Soon, at just the right angle, we could see a few masts sticking up against the trees in the background. Then the lighthouse and the harbor mouth. We’d made it.

Under a softly rising moon, we motored up the narrow channel and into the harbor at Meaford. At Richardson’s Marina, the attendant emerged. “Where’d you guys come from?”

“Killarney,” Bill answered. “We sailed down here to put her up for the winter.”

“Welcome,” he said, shaking his head. “Tie her up and come on in. You guys must sure know what you’re doing to make a sail like that this late in the season.”

It took a long while for Bill and me to stop laughing.

Several times on that first sail I swore that if we ever found Meaford, I’d never leave dry land again. But the bug had bitten. It was the terror and uncertainty of that voyage; those were the hooks that grabbed me and haven’t let go. To this day, every time I slip the lines and leave the dock, I am never really sure what’s going to happen. Weather changes, equipment fails, and unexpected circumstances arise. These mostly never come to pass, but there is always that tension of possibility that lies just beneath the serene quiet of the wind powering me to whatever adventure awaits.

Many boats, and trips, and ports, and storms, and calms, and sailing friends later, I’m suddenly an old salt, walking down the dock past a kid proudly swabbing his decks. I stop, smile, and quietly say, “You might want to put a figure eight knot in the ends of those jib sheets, just so they don’t slip through the blocks in heavy weather.”