Shooting stills and video for cruising articles

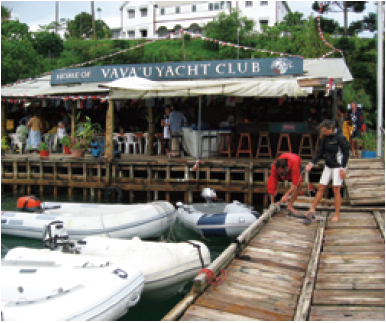

To get photos with a difference, take your boat away from marina situations and find surroundings that are out of the ordinary.

Magazines need photographs and pay well for them. Sailors are hungry for sailing DVDs, and the Internet is making it far easier to market videos. Cruising can give you time to practice these skills plus wonderful subjects to shoot. Digital cameras and camcorders have never been more affordable. Storage capacity is cheap, and instant playback allows you to take lots of photos or footage, see the images almost immediately, and go out and get better shots at no extra cost. Online resources and excellent books are available to help you along the way. But the other side of the coin is that you will be competing with true professionals in both fields, and they took lots of time to learn their trade. So how do you slant the chances more in your favor?

Although the equipment and techniques for still photography and video have their differences, they also have a lot in common. The first rule of photography is: you need the right equipment and you need it readily available. It does not have to be the most up-to-date, expensive equipment. In fact, simpler is often better — for dependability and ease of use and also to stop you from playing with features you really don’t need. Bob Grieser, a highly successful nautical photographer, states, “I forget all the bells and whistles, set the camera so it is correct for the current situation, then get out and watch for the moments I want. Once I start shooting, I can’t be playing with settings — I might miss the action.” Tory Salvia, a video producer and creator of thesailingchannel.tv, has been producing videos for three decades.

He agrees with Bob: “You can get video gear today to do things we didn’t even dream about 10 years ago. But that also means you can waste time playing with optional settings. The best thing newcomers can do is stick to the most basic camera, use the most basic settings, and worry about framing good shots.”

Choosing still cameras

Bob strongly recommends a single-lens reflex (SLR) with interchangeable lenses: “Very few built-in zooms produce the same quality pictures.” A wide-angle lens is vital, especially for interior shots. The largest lens he feels you can use on board is 300mm. Larry and I have found that we get “camera shake” with anything larger than 200mm. Bob recommends something like a Canon EOS Rebel as a good starter camera. When I mentioned we were using a five-year-old Nikon D40, he said, “That’ll still do the job. It has been replaced by the D80 and at about $700 it is great for someone working toward being a pro. For today’s editorial requirements, you need 8 to 10 mega- pixel (MP) capabilities.”

Lin and Larry’s Tongan goddaughter, Linlarry (called lini for short) was supposedly conceived the evening after her parents had dinner (and some extra wine) aboard Taleisin during the Pardeys’ visit to Tonga 23 years ago. They were delighted to finally meet her and her daughter when they visited again last year.

You need a weatherproof shield. To get good sailing shots, your camera will often be out where spray is flying. We do not recommend a waterproof casing for your main camera. If you intend to take a camera in the water while you swim or dive, a relatively inexpensive dive camera would be a better choice. If it did get damaged, you wouldn’t be left without a camera.

As mentioned above, the basic rule is that you need a camera when you see a picture. For that reason, we also carry a good-quality point-and-shoot camera that fits in my handbag. That way, we have a camera with us almost all the time. This seven-year-old 2MP camera has earned us more than our fancier gear has, because the “detail” pictures we get with it are very marketable: a stern anchor setup Larry snapped during a stroll through a marina, snapshots of people we meet along the way, gear we see at a boat show.

Everyone loves photos of people, but always ask before taking personal photos. Lin finds folks rarely refuse, especially if she can get them laughing beforehand

We have two batteries and two memory cards for each camera. With luck, this means we will always have a camera in working order, a battery with a charge in it, and lots of photo space ready for immediate use.

Choosing video cameras

Once again, simple is better. Do not be impressed with small size. You will find that it is far easier to hold a larger video camera steady as you shoot. From the moment we decided to make a video, we carried two identical cameras. Video cameras are far more sensitive to shocks and moisture than still cameras. We found that having a backup paid dividends in another way. When we were in unique situations, such as on the beach at Rio, or at a street party in Angra dos Reis, each of us would use a camera. We seemed to shoot from different perspectives, and we even shot each other shooting footage. I caught a wide-angle shot while Larry was getting a close-up. This gave our editor a variety of images that worked far better than video shot only from one point of view.

Tory Salvia recommends buying a video cam with HDV capabilities. “This is the future of video,” he says. “New videographers should shoot in at least HDV (1080i or 10080p) to future-proof their work. (You can always “down-res” to Standard Definition (SD).) Tory suggests buying the next-to-last version rather than the latest and greatest. “You’ll save 30 percent and won’t miss any so-called, newest, greatest feature.” In 2009, his favorite for on-board shooting was the Canon HV20, which is less than $1,000 — compared to its newest rein- vention, the HDV30, at close to $1,499.

Do not be impressed with extreme zoom capabilities. Even with a tripod and a built-in steady cam, you will not get usable footage with anything higher than a 6-power zoom. Handheld, a 2-power zoom is about all that works well.

A tripod is essential. Larry rigged a clamp and adjustable fitting that let us position the video cam almost anywhere on the boat. It clamped to the boom gallows, the edge of the sliding hatch, the backs of settees. It helped him shoot both of us working together on deck or setting oil lamps on his own while I was sleeping belowdecks. A water-resistant case or shooting hood is vital, plus a waterproof case for at least one of the video cameras. If you want to speak to the camera, or interview others for your program, you need a separate lapel-clip microphone with at least 12 feet of cable. You don’t have to spend much money to get a good one. When our $400 Sony microphone failed as we were doing the final narrative for our Storm Tactics DVD, we had to use a mike we had bought at the local hobby shop for $30. In the editing suite, we were asked, “Nice sound, what mike did you use?” You can hear it for yourself — about 10 percent of the sound for Storm Tactics was done in a studio, the rest on our cheap mike. We also carried a wide-angle-lens adapter so we could get better shots inside the cabin and in the cockpit.

No one will be impressed with a bulky, professional-looking video-cam case. In fact, such a case could invite theft. A low-key, nondescript bag will make your cameras less interesting to anyone with sticky fingers. When we dinghy ashore, we try to use the smallest possible padded bag that will hold our video cam and put this inside a waterproof carry bag, along with a small hand towel. We use the towel to wipe salt from our hands when we want to use the cameras.

Good pictures: a few hints

Whether moving or still, pictures have to tell a story. Take a good look at an array of National Geographic magazines. Read a few of the stories, then study the photos. You’ll see that the photos often tell a different but parallel story. Next, look at your favorite sailing magazines and see which pictures grab your attention. They’ll most likely be photos of people. Everyone likes to see what others look like. To make people look good, we try to get them to take off their sunglasses and their hats, if possible. Let us see their faces. If it is a hot, sunny day, try to maneuver your subjects into the shade of the sails for close-ups. Get people busy doing something and then take lots of photos quickly. When they are occupied, they forget about the camera.

Always carry with you a good quality pocket camera (but not so expensive you’d be devastated if you lost or drowned it) so you can get spur-of-the-moment shots you would otherwise miss.

Be sure to take a wide-angle, a middle-range, and a close-up picture of any interesting situations. No matter how high the resolution of a picture, you can’t crop a wide-angle shot to make a good close-up.

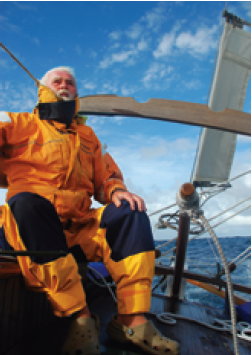

If the crew wears bright-colored clothing, it makes your photos look even better.

For the best-looking pictures — ones that have wonderful, rich colors — get up early. As a general rule of thumb, professionals don’t shoot between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., because the light is too flat and unflattering.

Lin had her camera with her when she and Larry went to a church fundraiser in Tonga and was able to unobtrusively snap the feast.

As you shoot, think about a story and get other pictures to fit with the ones you take. If you see a beautiful sunrise in a tropical setting, how about a shot of the tropical fruits filling your stores locker, your crew drinking from fresh coconuts, someone diving overboard into crystal- clear water, and the anchor of the boat dug into white coral sand? Since there is no cost for film, shoot lots of pictures. View them all and then cull them. First, delete every one that is not perfectly sharp; next, get rid of any you don’t like. Then go away for a while, come back later, and get rid of 50 percent of the rest. You will probably end up with a useful selection of workable photographs. (National Geographic photographers say that they average one marketable shot out of 36.)

If you find a subject truly interesting, be sure to take a wide-angle, a mid-range shot, and close-ups. Where you can, use the light to create varied effects. you’ll be pleasantly surprised to find editors often use two or three shots of the same subject this way.

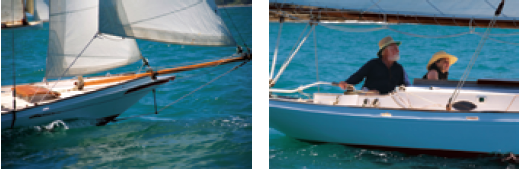

Get photos of your boat under sail. Anchor your dinghy, then have your partner sail the boat around you. For dramatic shots, consider climbing a hill and shooting while your crew sails through a narrow passage. If you meet another sailor who has photographic skills, ask her or him to use your camera and take pictures as you sail alongside. If you have a chance to get on board that boat, take shots of your partner sailing alone. We have also obtained some book and article illustrations by having our calling card available when we see someone taking a photo of our boat. We offer them our card and ask for a copy. Two out of three eventually send them. If we receive payment for that photo, we split the gains with them.

Special shooting tips for video

It was almost 20 years ago that Roy Blow of A-V Creative Services, an Australian video producer, suggested that we make a program together. He provided a camera (Hi8) for us to use and said, “Don’t try to take moving pictures. Instead, frame up and take good still shots, and then let the images in the frame move. Make sure you keep the camera running for a few seconds after the action stops.” He sent us to watch commercial films, and soon we began to see how each scene was made up of dozens of short clips, the camera rarely zooming in or out, rarely panning to follow the action. Roy reminded us to take close-ups, mid-range, and wide- angle shots and also to shoot the same scene from several different angles and get extreme close-ups. For instance, when Larry filmed me hoisting the drifter, he shot my face, over my shoulder, from the stern of the boat looking forward, and from the bowsprit looking aft. Then he got in close and showed only my hands on the winch. We have learned that it pays to script even short video sequences on the boat to make sure that we cover all these angles.

Learning to use a tripod is vital, but even more important is learning to be a tripod when you are shooting on board. Practice leaning against the mast to hold your body steady. Learn to put your elbows against your chest to steady your camera. If you plan to pivot while taking a shot, practice first so you will know how to place your feet so you stay steady as you follow the action.

There are downsides to shooting video programs. First, you have to keep your boat looking tidy at all times — lines coiled, sails nicely stowed. You have to look sharp when you are sailing, too. Otherwise, you will miss the good shots while you rush around tidying up, or you won’t want to use shots with frayed or scuffed gear showing in the background, or others with the sails luffing or poorly trimmed. Second, you can get in trouble by forgetting seamanship just because you are shooting something interesting. We came close to plowing right into the chase boat in Fremantle, Australia, because we were so busy trying to make everything look good as we were being filmed. Another time, we actually put ourselves and the boat at risk. I was up the mast shooting footage, the windvane was steering, and Larry was running out the bowsprit to add some action to the shot. We realized soon afterward that had Larry accidentally gone off the bowsprit, the boat would have sailed herself right onto the rocky island a quarter of a mile ahead, and, since I was secured by safety lines, I could not have done anything about it. It all sounds amusing now, but it left us rather shaken at the time.

Tory Salvia recommends subscribing to lynda.com for $25 a month for access to literally thousands of tutorials on all aspects of video work. I also went online and searched “Learn to make videos.” A large selection of well-known names came up, offering very low-cost or even free tutorials. For a crash course on travel videog- raphy, however, Tory recommends The Travel Channel Academy, a four-day intensive course with a tuition of $2,000 travelchannelacademy.com.

But the first step is to watch films more critically, then watch the videos that are selling in your chosen field. According to a very quick and unscientific survey of top sellers through Amazon.com, Latitudes and Attitudes, thesailingchannel.tv, and West Marine, the films with which you will be competing are, in no particular order: Blue Water Odyssey, Being Out There, Cruising with the Shards, Storm Tactics, and Cruising Has No Limits. Only one was produced by professional TV folks, the Shards. The others were shot by sailors just like you but edited by commercial video editors. In no case are they of National Geographic quality, but each of the programs has good content with solid how-to information, even if the story is based around a family cruise.

Whenever Lin and Larry see folks taking pictures of Taleisin, they try to sail up close and ask if the photographer could please send copies of the photos. They pass over one of their cards with a note promising to give credit for the use of the photo plus any payment they receive. When they saw Darren Emmens shooting pictures near Seattle, they didn’t know he was a professional, but when they saw his work, they were glad they’d approached him and made the offer.

This article is an excerpt from Lin and Larry Pardey’s Capable Cruiser, third edition, which was published in 2010. The information, such as the technology discussed here, has been extensively revised in this new edition.

At the time of publishing this article in the May/Jun 2010 edition of Good Old Boat Magazine, Lin and Larry Pardey had just received the Cruising Club of America’s Far Horizons Award. They recently sailed from the U.S. West Coast to New Zealand and are now gunkholing along the east coast of New Zealand on board Taleisin while they upgrade a 21 foot trailer/sailer so they can try brown-water sailing on some of the dozens of river estuaries along New Zealand’s west coast.