Controlling your environment makes you a better, safer sailor

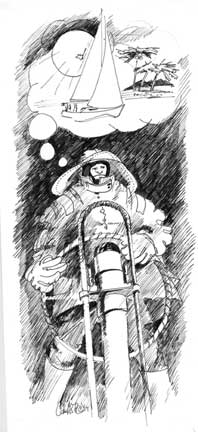

As a person to whom quality time and time aboard are synonymous, I often daydream of idyllic passages through tropical seas with steady trade winds, puffy white clouds, and sun-sparkled wave tips at my back. Moments later, reality returns to find me clutching a warm coffee mug and watching my steaming breath join the rest of the condensation coating a frigid cabin. Or it finds me pondering, with burning eyes, the flies gathered on the mainsail during a windless, steamy August afternoon.

We need to cope with an amazing range of temperatures and conditions over the course of a typical boating season. Moreover, we do it in a comparatively Spartan way, without a basement full of extra equipment. We do our best to cope with this temperature range for two basic reasons: comfort and safety. A sailor preoccupied with discomfort is going to be at a disadvantage when decision-making time suddenly arrives.

Basically, we must address two environmental issues while boating; how to stay warm when it’s cold, and how to cool off when it’s hot. Let’s look at the mechanics involved and then take them in turn.

Heating and cooling are two sides of the same coin: the physics of heat transfer. When heat is transferred from place A to place B, A will get cooler while B gets warmer. There are three ways that heat is moved around:

- By conduction, when your hand touches a hot stove, directly transferring the stove’s heat.

- By convection, when fan-blown air delivers heat from the stove.

- By radiation, when the hot stove’s surface or its flames emit infrared waves that warm the objects that absorb them.

Those are warming situations; but keep in mind that if you were the stove, they would be cooling situations . . . different sides of the same process. To stay comfortable, our human efforts are directed at either enhancing or reducing the transfer of heat.

Staying warm

Types of heaters

There are several ways to combat cold. Each of the following five basic types of marine heat generation has advantages and disadvantages.

Electric heat is quick, inexpensive to install, very easy to start and adjust, requires no exhaust venting, and doesn’t add moisture to a boat’s already moisture-laden atmosphere. It is also impossible to use away from the dock without running a generator. Electric heat must be carefully designed to prevent shocks and fires. And, finally, not all marinas provide sufficient power to run these heaters. There are electric furnaces with blowers and air ducting to efficiently heat the long skinny interiors of boats, but many medium-sized boats can do quite well with a portable, fan-assisted electric heater. If your home port is north of the Mason-Dixon Line, dockside electric heat represents a good investment for chilly mornings and evenings, often extending a season by two or three months. When buying a portable heater, make sure that it has:

- a three-pronged safety plug;

- a thermostat that shuts it off at the desired temperature;

- a tip-over sensor (if it’s portable) that shuts it off should a wake or other sudden motion knock it over; and

- a ground-fault interrupter (GFI) or receptacle. In fact, all alternating current-powered appliances aboard should have, or be plugged into, a GFI.

Those precautions, along with sensible and prudent operation, will make electric heat an enjoyable convenience.

Solid-fuel heaters have the advantage of burning a wide variety of readily available fuels such as charcoal and wood. They produce a quiet, dry heat and sometimes a nice ambiance if the fire is visible. The price is also moderate, and they can be used under way or while you’re swinging on the hook. On the downside, they do require venting, and their smoke can foul sails or topsides. They take the longest of all heaters to begin producing heat, and a bag of charcoal is not the cleanest item to be rattling around in a locker. Finally, burning ocean driftwood can create mildly corrosive smoke that hastens your heater’s demise. Still, solid-fuel heaters, with their warmly glowing flames, rank second of all heating types with traditionalists.

Propane, butane, and compressed natural gas (CNG) are gas fuels with some commonalities. They are quick to produce heat and difficult to fine-tune; they will work at the dock or under way; and they are clean-burning.

Most require venting, and I would advise against those that don’t on two grounds.

First, some of the catalytic types that don’t require venting are designed for a semi-open space with plenty of fresh air moving through . . . and moving the waste products out as well.

Second, the combustion process for gas fuels produces a lot of water vapor that will be deposited in the dark cold corners of your boat unless it is vented outside with the other fumes.

There can also be a definite fire hazard when you use a portable catalytic heater in your boat, especially while under way. I would caution against doing it. Period.

CNG is lighter than air and will, therefore, not settle in the bilges like propane could. CNG is also much harder to find than propane wherever you sail. Propane is quite safe when it’s installed with properly isolated storage bottles, a correct solenoid shut-off valve, systematic maintenance of the lines, and a good gas-detection alarm. If you already have propane for your galley, it may make sense to use it for heating, also. Permanent marine propane heaters are more expensive than solid-fuel ones, but less expensive than liquid-fuel heaters.

Liquid-fuel heaters are primarily kerosene- and diesel-fuel heaters. They are the benchmark by which traditionalists rate all others. They provide a steady source of low-cost heat while under way, on the hard, and all points between. If you already have a diesel-fuel galley stove, you probably don’t need a heater, since the stoves I’ve been around warm a cabin very well.

The heaters require venting, and the smoke can stain sails over a period of time. They are also among the most expensive of the different types of heaters. Since they require gravity-fed or pressurized fuel, a special tank is sometimes the easiest way to install the system.

Lastly, your cabin can get smoky if fluky winds swirl fumes from the stack back around the mandatory open hatch or port. A diesel-fuel heater is for hard-core sailors who rejoice in the glitter of frozen halyards. Serious stuff.

Alcohol heaters are portable and inexpensive, but not in the same league as kerosene/diesel types. Their flame is difficult to see, increasing the possibility of burns, and they pump lots of undesirable water vapor into the cabin air. It’s hard to recommend them for boating purposes.

Hot-water radiators. This last heat source is probably the least used. Radiators produce heat from the water used to cool your inboard engine. These are not often seen on sailboats, despite the fact that many a voyage transforms our wind yacht to a displacement-powerboat-with-mast.

Radiators work only when the engine is running, which allows powerboats to make good use of the free, quiet heat. They produce a dry heat with no venting required, no fire danger, or smell. They begin providing heat within minutes of the engine’s being started, and are easy to adjust. Most installations are custom-made and, therefore, can be expensive. The radiator preferably uses the heat-exchanger fluid since it’s hotter, but raw cooling water can be used – although a broken hose or fitting could flood the cabin.

Humidity’s effect

Humidity, or water moisture in the air that you’re heating, makes a difference. The more water moisture, the more heat that air can hold. Dry air requires a higher temperature to be comfortable. Since most heat sources do not add water vapor, the air becomes drier as it gets warmer. Unless you have the perfect boat with bone-dry bilges, chain stowage, lockers, and bedding, you probably won’t have to worry about over-dry air while bobbing on the waves. The exception would be heating while hauled out during sub-freezing winter weather; then a pan of water boiling on the stove might help.

Circulation – air layering

The numbers game

There are formulas for converting watts to Btu (British thermal units), determining resistance to heat loss (insulation factor), and number of tons of air conditioning needed. But forget the numbers; boating’s wide array of types and conditions make them impractical. Your electric heat will be limited to what your marina can provide: typically enough to run a 1,600-watt heater at 110 volts.

With care, this will keep a saloon and one stateroom comfortable down to around freezing . . . remembering that comfort is a relative term. Any requirement greater than that in size or temperature is going to require a fuel heater. Heaters made for permanent marine installation will advertise figures in Btu output, but basically they’ll be good for boats up to about 45 feet and temperatures down to 300F. Dealers in marine air conditioners will help you figure your cooling requirements based on climate, boat insulation, and installation location.

A boat has a lot of nooks and crannies, is poorly insulated (compared to a house), and usually has a single point of heat. If a fan isn’t used to push the air around, the nooks and crannies and outer surfaces stay clammy while the air immediately above the heat source becomes uncomfortably warm.

Unless those on board can levitate to the 720F air layer, everyone is going to be miserable – cold and clammy from the knees down, and feverish from the shoulders up. A fan is essential for heating comfort. Small, low-wattage fans can be mounted in passageways forward and aft to immensely improve the main fan’s function. Layering is good for clothes, bad for cabin air.

Ventilation

An airtight heated cabin is an invitation to disaster. At the very least, you’re inviting headaches, as the oxygen content is depleted by fuel-burning heaters. Carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide levels increase, aggravating the stale conditions. Moisture from respiration and perspiration has no place to go to, except onto exposed surfaces. It will cake your sugar and salt into unusable blocks. You need to have a hatch, porthole, or Dorade vent partly open, even if it’s below freezing and snowing sideways.

Drafts

The opposite of an airtight cabin are drafts so bad that a candle or lantern can’t stay lit. This is unworkable, because all the air that you’re heating is leaving. It’s going to take a lot of fuel to raise the temperature if you’re heating the entire Western Hemisphere. You don’t need all downwind hatches open . . . maybe just one, or a half of one.

Clothing

Don’t overlook the value of dressing for temperature rather than changing the temperature for your dress. It’s quite possible to be comfortable at 550F or cooler temperatures with warm boots, hats, and gloves. You lose the most heat from not wearing headgear . . . a warm hat and scarf are probably worth 50F of cabin temperature by themselves. You’ve heard it before, but dress in layers: a layer closest to the skin that will wick moisture away, then a bulky insulating layer or layers to hold body heat in, finally an outer layer that’s wind-resistant, to reduce loss of heat by convection or drafts. If you typically sail in colder weather, have boots large enough for two pairs of socks and make the outer layer a pair of good-quality wool . . . wool retains heat even when it’s wet.

Keeping cool(er)

For many sailors, comfort means any way to stay cool on hot days. For some, staying cool is synonymous with air conditioning, but there are other approaches.

Air conditioning

Marine air conditioning is much like marine electric heat; it works well with shore power, with gen-set power, or with an extremely long extension cord. For powerboaters, there are air conditioners that work from a power take-off on the engine. Like radiator heating systems, the engine has to be running for power take-off systems to operate. Air conditioning accomplishes at least four things: it cools the air, creates air movement, removes excess moisture, and filters some airborne particles.

It also requires a well-sealed cabin to be effective, and a compressor location with plenty of fresh-air circulation to take away the heat. Systems can be on the pricey side, but if you’re lying alongside the dock at West Palm Beach for an extended stay in July, life as we know it suffers without AC.

Circulation

Air circulation helps in reducing the effects of uncomfortable heat. It promotes the evaporation of perspiration, which lowers our body temperature and makes us smile. If your boat is swinging on the hook, or otherwise moored on a windless day, circulation is spelled f-a-n-s.

For a very few dollars (less than $10) mail-order suppliers such as Northern Hydraulics or Harbor Freight often sell small, surplus, 12-volt box fans that draw less current than a light bulb. You may even find some that have hinges, so they fold against a bulkhead when not in use. Having two of them in the main saloon and one in each stateroom is not overkill, andyour batteries won’t go dead in a day, either.

For best results, aim them directly where people will sit (or lie) at about chest level. They make a big difference and also help during the frosty season for distributing your heater’s munificence. If you run your engine about an hour a day, your batteries will never suffer any undue drain.

Under way or on any windy day, circulation is spelled h-a-t-c-h-e-s. The more, the merrier. The bigger, the better. Opening ports are nice but usually too small, and their insect screening further reduces the airflow.

Ideally, on a good old boat of about 35 feet, there should be two hatches in the cabin overhead, one above the galley and one above the seating area. There should also be an overhead hatch in each stateroom. All of this is in addition to opening ports.

Incidentally, I don’t like forward-opening hatches in the V-berth area or anywhere else. Boarding seas will quite likely carry them away if they catch them undogged. Trawlers, whose foredecks are much higher, fare much better with forward-opening hatches.

Ventilation

Hand-in-hand with circulation goes ventilation. On hot sultry days, you need fresh air below, unless you’re running the air conditioner. Seasickness is not eliminated by fresh air but it sometimes helps. And fresh air always helps those who are aboard with the seasick victim. Fresh air also means keeping engine room air separate from cabin air. Even in a spotless engine room without exhaust leaks, engines get hot and fill the air with lubricating-oil fumes and bilge fumes. They need lots of fresh air and ventilation, but not via the cabin.

There is one particular no-win situation: running downwind under power. It’s much better to bear off a few degrees than to suffer the exhaust fumes in the cockpit and cabin, no matter how good your ventilation is.

Liquids

Our natural cooling systems depend on the evaporation of perspiration (sweat) to reduce body temperature. The moisture for sweat is carried by the vascular system. If you don’t drink sufficient water, your blood doesn’t have as much to give the skin, and you’re going to feel warmer.

Drinking lots of liquids on hot days helps our cooling systems. Taking salt tablets helps the body increase the vascular volume, thus more liquid is available for the skin. For those of us on the far side of 39, perspiration is generally reduced. We therefore really appreciate any additional cooling efforts.

Humidity

Increased humidity slows our rate of perspiration evaporation, and thus our cooling off. You will feel more uncomfortable at 900F and 90 percent relative humidity (RH) than at 900F and 50 percent RH. Aside from cranking up the air conditioning or heading for the clubhouse, combating high humidity requires shade, air movement, and loose-fitting clothing.

Shade

The value of shade is often underestimated when you’re trying to cool your boat. A Bimini top is wonderful for the cockpit if the sun is directly overhead. Short side-panels dropping down from the Bimini about a foot will increase its shade area by at least 50 percent and won’t noticeably reduce the ventilation, especially if the panels are made from weighted screening. Lastly, consider a Bimini extension over the cabin roof. Shading this area will definitely make the cabin cooler and help the air conditioner.

Article from Good Old Boat magazine, January/February 2000.