While economics favor the sloop, other rigs have much to offer

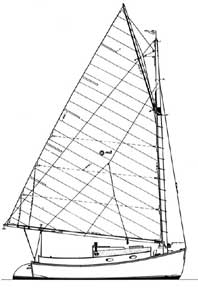

Sunshine, a 33-foot gaff sloop with a bowsprit

The history of the fore-and-aft rig is a fascinating one. It is particularly interesting when you realize that two of the earliest fore-and-aft rigs, the lateen sail of the Middle East (Egyptian feluccas and Arabian dhows) and the Chinese junk, have remained largely unchanged over the centuries and are still in use in the areas where they began.

21-foot catboat

Conversely, in the West, the fore-and-aft rig has been under constant development: from the dipping-lug rig based on the old square sails to standing lugs, gaff rigs, and finally to “leg o’mutton” sails, spritsails, and the modern Bermudan rig. And, of course, the rig is still being developed with newer materials, fully battened sails, mechanical vangs, in-mast reefing, sprit rigs with wishbone booms, and so forth.

Readers will note that I use the term “Bermudan” rather than “Marconi.” The reason is that the rig first became more widely known in the late 1600s after reports reached Europe of the good performance of the small sloops of Bermuda. So I prefer to use the island name, rather than call it after a radio mast that was not invented until 200 years after a Bermudan rig first caught the breeze.

Gaff vs. Bermudan

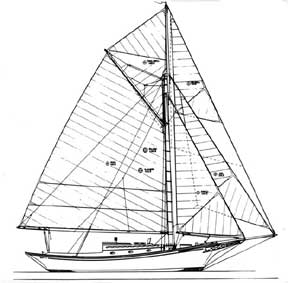

Sandingo, a 42-foot sloop

The gaff rig and the Bermudan are the two major rigs today. Each has its advantages, but truly they operate on different planes. The racing sailor and the average yachtsman stay with the Bermudan rig, while the gaff is favored by a few diehards and is used, of course, for character boats and replicas.

The gaff rig does feature a lower center of effort for a given sail area and so develops less heeling moment. This is partly offset by the heavier weight of the spars, but the weight of the gaff comes down as the sail is reefed. Furthermore, a quick “reef” can be achieved in a squall by dropping the peak halyard to scandalize the sail and immediately reduce the effective mainsail area by 30 to 40 percent. The gaff sail itself is slightly more effective offwindthan the Bermudan as it presents a flatter area to the breeze and, in addition, the gaff can be fitted with a vang to reduce twist. More important to the serious cruising sailor is that the gaff rig is simpler and cheaper to set up, less sensitive to bad tuning, and generally simpler to repair if something goes wrong at sea.

42-foot double-headsail sloop

The gaff rig hasn’t had the advantage of the development that has gone into the Bermudan rig in the past 50 years. The British designer, J. Laurent Giles, showed the gaff rig the way over a half-century ago with the lovely 47-foot gaff cutter Dyarchy. Her single-spreader rig supported a tall, wooden, pole mast with an unusually large main topsail’s luff rope sliding up into a groove. Despite Dyarchy’s success, this did not stir interest in further development unfortunately, so the gaff rig of today is little changed from that of a century ago with the exception of synthetic sails and, possibly, aluminum tube spars.

The contemporary, highly developed Bermudan rig, with its lighter spars, higher-aspect-ratio sail, inboard chainplates, close jib-sheeting angles, and so on, has much the better windward ability. Also the development of the spinnaker and (more importantly to the cruising sailor, the asymmetrical spinnaker) has more than offset the gaff rig’s advantage downwind. A major feature of the Bermudan rig, of course, is that a permanent backstay can be fitted, adding to safety and reducing the need for running backstays.

For these and other reasons, such as rating handicaps and manufacturing economy, the Bermudan rig is vastly in the majority today for cruising and racing, while new gaff-rigged craft are few and far between. Still, the gaff rig finds favor with those who love traditional craft andreplicas of the working sail of yesteryear. I’ve been fortunate to have been commissioned to design a wide range of gaff-rigged yachts, from 25-foot catboats and Bahama sloops to 70-foot schooners, and I know that our waters would be very dull indeed if the gaff rig ever vanished completely.

Efficiency

In the 1960s, the Royal Ocean Racing Club of Great Britain developed a handicap rule that estimated the efficiency of the various rigs:

|

Rig |

Handicap (%) |

| Bermudan sloop or cutter Bermudan yawl Bermudan schooner and gaff sloop Bermudan ketch and gaff yawl Gaff schooner Gaff ketch |

100 96 92 88 85 81 |

In effect, the rule said that a gaff ketch rig has only 81 percent of the efficiency of a Bermudan sloop or cutter of the same sail area, but that was with other things being equal. That’s not always the case, and it is obvious that a gaff ketch with a well-designed hull and a slick bottom can sail circles around a poorly designed Bermudan sloop with ratty sails and a rough bottom. Also, the cruising sailor must consider that efficiency is not necessarily handiness or safety. Safety in cruising is having sufficient windward ability to claw off a lee shore in a gale, but only if the rig can be handled by a short-handed crew. If a sloop’s sails are too large for the crew to change or reef under storm conditions, then you have no safety and would be better off with a divided rig with its smaller sails and greater ease of handling.

Rigs

Until the 1980s, the cat rig was limited to small character boats, usually gaff-rigged, and designed along the lines of the Cape Cod model.

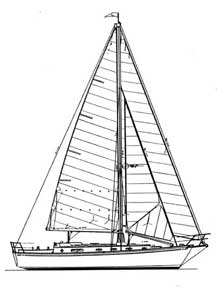

29-foot sloop

Now we have beamy fin keel/spade rudder Nonsuch catboats in sizes to 36 feet, spreading over 700 square feet in one huge sail. I know from racing against them that these new catboats sail well to windward, certainly much better than the old gaff-rigged cats, but how much of that is due to the rig and how much to the modern hull design is open to question.

Cat rigs

The cat rig is certainly suitable for coastal cruising, with an eye on the weather, but I don’t consider any single-masted cat rig, not even the most modern, to be a true bluewater cruiser. Someone will cross an ocean on one, probably has already; oceans have been crossed in all manner of small craft, from rowboats to sailing canoes . . . just not with me aboard!

Sloops and cutters

The sloop rig and the cutter are almost indistinguishable today. If the boat sets only a single headsail, she is a sloop, of course.

Blue Jeans, a 46-foot cutter without a bowsprit

With or without a bowsprit, if the mast is set well aft, abaft 40 percent of the waterline length, and the boat carries two or more headsails, she is a cutter. Confusion arises when a boat has her mast located forward but sets several headsails. Many will call her a cutter but she is, in reality, a double-headsail sloop. Even with a short bowsprit she’ll be a sloop unless the foretriangle is larger than the mainsail.

37-foot triple-headsail sloop

The sloop and cutter are the most efficient of all rigs. Indeed, a sloop with a self-tending jib would be as easy to handle as a catboat and a better all-round performer. The single-headsail sloop usually has a slight edge over the double-headsail rigs, as the staysail is not an easy sail to trim for maximum performance. Properly set up, either rig is simple to handle, and with modern (and very expensive) gear they are suited to cruising yachts up to 50 feet or more.

An important point with cutters and most double-headsail rigs is that running backstays are required to properly tension the staysail stay. Often, you’ll find an intermediate shroud fitted, running from the point where the staysail stay intersects the mast to a chainplatejust abaft the aft lower shroud.

Kaiulani, a 38-foot cutter

The angle this shroud presents with the mast is far too small to tension the staysail stay, so all it really does is add undesirable mast compression. On many designs I have fitted a heavy tackle to the lower end of the intermediate shroud so it can be left set up as an intermediate in light air and, when it breezes up, brought aft as a runner, properly tensioning the staysail stay and reducing mast panting at the same time. Don’t cross an ocean without one!

It should be noted that the most efficient setup for a given sail area is a sloop with a large mainsail and a non-overlapping jib. The big 150-percent masthead genoa jib beloved of modern racers only pays off under handicap rules that do not penalize the extra area of the overlap. In class racing where every square foot of sail area is counted, such as the 5.5-Meter class, the rigs quickly settle down to using the largest permissible main and the smallest jib to make up the allowed area. Such a rig can make good sense for the coastal cruiser also, as it simplifies handling. The main can be quickly reefed when it blows, eliminating the need for a headsail change. Tacking with the smaller jib is much easier on a husband/wife crew than handling a whopping big genoa. Such rigs were once common but are now out of style in this era of masthead sloops.

Yawls

Julie, a 52-foot yawl

Despite the efficiency of the single-masted rigs, my own preference for bluewater cruisers over 40 feet is a divided rig, the yawl or ketch. A true yawl has the mizzen set abaft the rudderpost and the sail area about 10 to 15 percent of the total. It’s a useful rig with some of the advantages of both the sloop and ketch. It is almost as weatherly as a sloop and, like the ketch, can set an easily handled mizzen staysail to increase area in light air or jog along under jib and mizzen in a blow. At anchor, if you leave the mizzen set with a reef or two, the boat points quietly into the wind and no longer sails around its mooring. The yawl’s mizzen must be strongly stayed so the sail can be set to balance the jib in heavy weather and, in a real gale, to keep the yacht head-to-wind with a sea anchor off the bow. It’s difficult to design a yawl today, though, as the rudders on contemporary yachts are usually so far aft that you’d have to tow the mizzen in a dinghy for it to be abaft the rudderpost.

Ketches

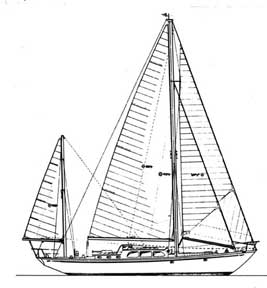

A 44-foot ketch with a small mizzen

The ketch has her mizzen forward of the rudderpost, and the sail area is comparatively larger than that of the yawl’s mizzen, up to 20 percent or more of the total. As a result, the ketch is slower and not as weatherly as the yawl because the large mizzen is partially backwinded by the main when beating to windward. The answer is to design ketch rigs with a smaller mizzen, closer to yawl proportions. This makes a good compromise rig with some of the advantages of both. The mizzen mast can be well stayed, and the mizzen sail is not so large that it unduly affects performance.

Both the ketch and yawl can be balanced under a wide variety of reduced sail combinations in a blow and, to many cruising skippers, thishandiness more than offsets the loss of a fraction of a knot to windward. Both rigs can be built in smaller sizes, of course. I’ve owned a 22-foot ketch and 22-foot, 25-foot, and 30-foot yawls. Still, it is generally considered that over 40 feet is the proper size for the rigs, although I would not dismiss them in smaller sizes for extended bluewater cruising. The versatility and handiness of yawls and ketches can more than make up for an extra day or two at sea on a long voyage.

Miami, a double-headsail ketch with a bowsprit

By the way, there is no such rig as a “cutter-ketch” but I’ve heard a Whitby 42 called that when one is fitted with a bowsprit and double headsails. The term makes about as much sense as calling a Maine Friendship a “cutter-sloop.” The correct term is simply a ketch or, if you wish to be exact, a double-headsail ketch.

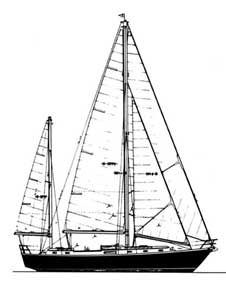

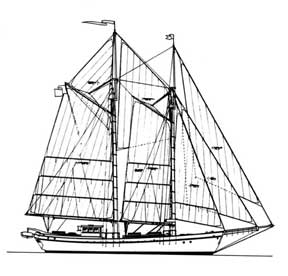

Schooners

The schooner rig is rarely seen today and, to my knowledge, there have been only two schooners in production in North America, the beautiful Cherubini 44 and my own little 32-foot Lazyjack (see January 2001 issue of Good Old Boat). The usual schooner is set up with one or more headsails, followed by a gaff foresail set on the foremast and either a gaff or Bermudan mainsail on the mainmast. The staysail schooner replaces the foresail with a staysail between the masts. Nina, a famous old staysail schooner, was winning silver from her first trans-Atlantic race in 1928 to her last Bermuda win in the late 1960s.

Tree of Life, a 70-foot schooner

A few schooners have been built with Bermudan sails on both masts. My Ingenue design was a CCA rule-beater of this type, winning a lot of silver in her day and beating many larger yachts boat-for-boat when the wind was free. Still, although the schooner is fast off the wind, she is not as weatherly as the sloop or yawl. A schooner can be a handy rig for cruising, though.

A well-designed schooner can beat slowly to windward in a blow with only her foresail set and is well suited to handling in adverse weather by a short-handed cruising crew. Schooners have been built as small as 20 to 22 feet, and Murray Peterson designed many traditional beauties in the 30-foot range. The rig is best suited to larger craft, generally of 40 feet or more, but if you like the rig and want a small schooner, go for it.

When I started in this business more than 40 years ago, the waters were dotted with schooners, ketches, yawls, cutters, and sloops of all types, sizes, and colors. Today, unfortunately, rating rules and the economics of modern mass production have decreed that the sloop rig is the way to go. Over the years, the factories have turned them out by the thousands, usually with blue trim or, like the bathtub in my home, all white with no trim at all. As sailors, we have lost much of our heritage, and our waters are a great deal less interesting as a result.

Article taken from Good Old Boat magazine: Volume 4, Number 2, March/April 2001.