In a previously published article, I touched upon the use of a quick and easy way for the lone sailor to raise or lower the mast on the typical small cruiser. Ensuing months brought a number of inquiries clamoring for more details regarding rigging. In truth, ponder as I might, I could never come up with a suitable mast-raising method on my own. However, I have a good friend, Gerry Catha, who is an airline pilot, aircraft builder, and fellow Com-Pac 23 sailor. He grew tired of my whining and worked out the following solution. I am grateful to him for redefining and perfecting the hardware involved and generously passing along the method to be adapted by his fellow sailors.

The instability of the stand-alone gin-pole has long made its use fraught with many of the same safety concerns associated with the use of trained elephants in mast stepping. The greatest fear factor involved in the process has always been the tendency of the mast-gin-pole combination to sway out of control during the lift. I can’t tell you the number of “wrecks” I have heard of, or been personally involved in (read, responsible for) over the years, due to a moment’s inattention, insecure footing, or errant gust of wind at some critical moment. All of this becomes a thing of the past with Gerry’s no-nonsense bridle arrangement.

While systems may differ slightly as far as materials and fittings go, the basic tackle remains the same: a six-foot length of 1 1/2-inch aluminum tubing, two 2-inch stainless steel rings, enough low-stretch 3/16-inch yacht braid for the bridle runs, a few stainless steel eyebolts, some snaps and, of course, a boom vang to take the place of the elephants.

Eyebolt installed

My own gin-pole has a large eyebolt installed in one end, which can be attached by a through-bolt (with a nylon spool cover) into a matching eye at the base of the mast’s leading edge and secured by a large wingnut. This is the pivoting point for the gin-pole, which, of course, supplies the leverage. On the upper end of the gin-pole, two smaller, opposing eyebolts provide attachment points for bridles, halyard, and boom vang. Again, I must say that I have already heard of a number of different variations regarding attachments, hardware, and so on, as each individual adapts the idea to his particular boat, budget, and attention span.

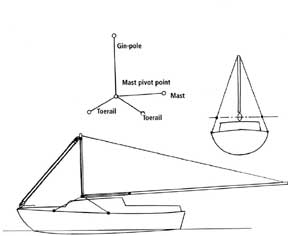

The critical thing to understand about this mast-raising technique is that in order for the mast and gin-pole lines to stay tight and keep the mast and gin-pole centered over the boat, the bridles must have their pivot points located on an imaginary line running through the mast pivot bolt. If the bridle pivot points are located anywhere else, the supporting lines will be too tight and/or too loose at some points during the lift.

There are two bridles. Each bridle consists of four runs of line, one end of each terminating in the same stainless steel ring, which forms the central pivot point of that particular bridle. In operation, this ring must be centered directly across from the mast step pivot bolt. The longest of the four lines will go to a point as high as you can reach on the mast (secured to a padeye using a stainless snap). The second longest run attaches to the top of the gin-pole, snapped to an eyebolt. The two bottom runs, your shorter lines, are attached fore and aft to stanchion bases, though a toerail will work as well. It is imperative that the steel ring be centered directly in line with the mast pivot point when all lines are taut. This is accomplished by the location and lengths of the two bottom lines.

There are two bridles. Each bridle consists of four runs of line, one end of each terminating in the same stainless steel ring, which forms the central pivot point of that particular bridle. In operation, this ring must be centered directly across from the mast step pivot bolt. The longest of the four lines will go to a point as high as you can reach on the mast (secured to a padeye using a stainless snap). The second longest run attaches to the top of the gin-pole, snapped to an eyebolt. The two bottom runs, your shorter lines, are attached fore and aft to stanchion bases, though a toerail will work as well. It is imperative that the steel ring be centered directly in line with the mast pivot point when all lines are taut. This is accomplished by the location and lengths of the two bottom lines.

Clip the jib halyard to the uppermost eye on the gin-pole and bring it to an approximate 90-degree angle to the mast and tie it off. Next, secure one end of the boom vang (cleat end) to a point as far forward on the deck as possible and the remaining end to the top of the gin-pole opposite the jib halyard.

At your leisure

With all bridle lines taut and the mechanical advantage of the boom vang facilitating the lifting, you can slowly raise the spar at your leisure. Since the mast and gin-pole are equally restrained port and starboard, they will go straight up or down without wandering from side to side. Using the auto-cleat on the boom vang, you can halt the process any time shrouds or lines need straightening or become caught up. This reduces the stress factor tremendously and allows for a calm, orderly evaluation and fix of the problem.

I might note that, due to variations in shroud adjustment and slight hull distortions, you may find the port and starboard bridle will be of slightly different dimensions, making it necessary to devise some sort of visual distinction between the two sides. I spray-painted the ends of the lines on each side, red or green, for instant identification. Stainless steel snaps on the rigging end of these lines make for quick and easy setup. I find that it takes us about 15 minutes to deploy the entire system and only 10 minutes or so to take it down and put it away. Each bridle rolls up into a bundle about the size of a tennis ball for storage. The bridles go into a locker, and the gin-pole attaches to the trailer until next it is needed.

Granted, launch time is extended by a few minutes, but the safety factor gained is immeasurable, especially for sailors who must perform the entire operation by themselves. I have used this method on masts up to 25 feet long and in quite strong side winds with no problem and have found it to be the most expeditious way to raise or lower a mast should trained elephants not be readily available.

Article taken from Good Old Boat magazine: Volume 4, Number 3, May/June 2001.