Bob Johnson at the helm

Robert K. Johnson, N.A., is the founder, chief designer, and CEO of Island Packet Yachts of Largo, Florida. The company is celebrating its 25th anniversary in the boatbuilding business, specializing in the construction of high-quality, luxury offshore cruising yachts. Bob Johnson is an imposing gentleman, tall, fit, and of great personal charm and authority. He’s an articulate and intelligent conversationalist. This interview was conducted in his office at the Island Packet facility in Largo, Florida, October 15, 2004.

GOB: You were originally trained at the University of Florida as a mechanical engineer before you specialized in naval architecture and marine engineering at MIT. Were you always interested in boat design or is it something you picked up along the way?

RKJ: No, I’ve had the bug ever since I’ve was a boy. I did my ninth grade “My Career” report on Naval Architecture and Marine Engineering and wrote letters to Chris-Craft and other companies to find out about careers in the field. My mother still has the folder of my report to the class. It’s been in my genes since I was born. I subscribed to Yachting when I was 8; I bought my own subscription. My dad had a small powerboat in Connecticut that we rebuilt in the garage before we moved to Florida when I was 14, but I always wanted to get into sailing. I wanted a pram, but we lived 50 miles inland in Connecticut and it just wasn’t going to happen when I was 12 or 13 years old.

In 1957, when I was in ninth grade, we moved to Florida and one of the first things I did was plan on building a boat. My parents bought a house on a canal in North Palm Beach. I bought plans from Rudder magazine for a 12-foot catboat, it had hard chines and a V-bottom, and it wasn’t a simple boat to build by any means. My dad was a machinist and an expert woodworker. He made his own machine tools and he was a big help, but it was still very much my project. I lofted it on the living room floor and built it on the carport. I altered the rig, installed a folding mast, and even changed the shape of the hull while I was building it. I put a bowsprit on it (boys love bowsprits because you get more sail area!) and I made it a gaff rig to shorten the mast so I could get under bridges. Before the rig was finished, my brother and I tested the hull by sailing it downwind with a beach umbrella for a sail. I’d never sailed before in my life. I built the boat first and figured I’d learn how to sail once I did.

GOB: But you started your studies in mechanical engineering?

RKJ: I wanted to start off with a strong foundation in fundamental engineering principles. I almost went into physics because I loved it, but I’m a nuts-and-bolts, hands-on kind of guy, so I stayed in engineering. I planned on getting a master’s, and between mechanical engineering, aeronautical engineering, and naval architecture three quarters of the principles are identical. A lot of it is hydrodynamics and fluid flow. Some of my exams and courses were related to aircraft, submarines, you name it. I feel I’m well rooted in the fundamentals and scientific method. I never took a business course, but there’s no such thing as perpetual motion or perpetual money, you have to account for everything. I would do it the same all over again.

GOB: I would imagine naval architecture is also broken up into specialties, wouldn’t it be different to design offshore platforms as opposed to, say, oil tankers?

RKJ: It’s like getting a medical degree. First you learn the body and how it works, from scalp to toe. Then you specialize.

GOB: Are the principles the same whether you’re building a yacht or a submarine?

RKJ: Yes and no. MIT didn’t dwell much on the subtleties of sailboat design, but you’re completely prepared to learn and use that information as applied to sailing boats or high-speed powerboats. That’s architecture, not naval engineering. If you want to design a propulsion system it’s going to take so many horsepower to move it, you try it out in the towing tank, you’ll want to determine plate thicknesses so it doesn’t break up in a seaway, that sort of thing. And there was a tremendous amount of published information available, even before the days of computers. That’s the engineering part. The architecture is the art aspect of it. The shape of a hull can’t be fully quantified. Computer programming can help because you can do an awful lot of modeling very quickly, and mathematical models can help you evaluate hull change. But ultimately you have to go out into the real world and try it. I graduated in ’67, 38 years ago, and there’s been a lot of new ideas since then or elaborations of older ideas: hydrofoils, surface-piercing vessels, and many others.

There’s a steady evolution, but new ideas too. Look at high-speed powerboats: Dick Bertram’s and Ray Hunt’s entry in the Miami-Nassau race in the late ’50s — there was no second place. The boat finished hours ahead of Number 2. It had this “wrong” deep V-hull with strakes on it which everybody has nowadays that could go through heavier seas faster without breaking something or hurting anyone. That didn’t come from an academic think tank, it came from an idea these guys had. That’s the art.

Think of high-speed sailing catamarans, guys are building these 30-knot offshore cats, breaking them, and reverse-engineering them to correct the problem. It’s much like the early days of aviation: build it, fly it, fix it, and hopefully survive. Our industry is full of wonderfully creative people who went out and did the wrong thing. Take the Hobie Cat; it can be hard to sail, and one of our dealers likes to tell the story of how he passed up on a chance to sell it because he didn’t think he could give them away. Now they’re a sailing icon. When I was in California making surfboards, Hoyle Schweitzer was the first person to popularize Windsurfers (it was his registered name, he owned that term) and he was able to get past the idea that if surfing is hard, if you put a sail on the board it’s harder still. But he had the vision to see that some people would learn how and he opened up a new market. Hoyle wanted us to make his boards, but we couldn’t see any future in it. Shame on me, and laudits to Hoyle for having that insight. That’s what I love about our industry: there’s always some new, clever idea out there. I’ve got several patents of my own I’d like to try out that I just haven’t had the time to do so. I have an idea for one powerboat that really deserves to be built, but I just haven’t gotten around to it.

GOB: In spite of this excellent background, I gather than your earliest job was working in missiles.

RKJ: Yes, we were designing anti-ballistic missiles. I worked for McDonnel-Douglas in Culver City: acoustics, shock, and vibrations. Shock and vibration are very important, they determine destructive loads; things don’t usually break under a static load, they shake apart. This proves the broad-based value of an engineering education. I took all the vibration courses (from Den Hartog) I could because they define structural loads and shock loading. My master’s thesis was on damages caused by setting off depth charges near a ship. In structures, you have masses, springs, and dampers. In a ship with water-born shock loads, structures are broken down for convenience into finite elements for analysis. 1966, I worked at a General Electric summer job where they had computer programs determining shock damage to reduction gear trains, but they were very slow, in those days computers were steam-powered. Missiles are designed the same way; I devised a process to show loads on critical components, using finite element analysis, and determining if it made a difference. I worked at M-D for two years,

There was a surfer who worked there with me and I had surfed, so he asked me what could a naval architect do to improve surfboards. I designed and patented an adjustable fin system for surfboards and wound up working for Wave Corporation for five years developing and making high-tech surfboards using aerospace materials. I installed my system and became a minority stockholder in the company. We developed honeycomb core surfboards, in those days, people were very anxious to use high tech materials in recreational products, and we felt we could increase performance by making surfboards lighter and more durable. Our final boards were very good but very expensive, and the market wasn’t really there. The kids who bought them just didn’t care. It was a marketing lesson, a classic case of Marketing 101 — make sure someone out there appreciates the features for value. The company went public, Karl Pope, an electrical engineer and surfer, was president, and I give him a lot of credit. He’s still making surfboards, and we still correspond. But I wanted to go back into boating and to my family back east.

GOB: Do you feel that your education or experience actually translates directly to your boat features or just as general background knowledge?

RKJ: Both. It’s an art: you build the type of boat you think the market wants and that you want to build, but our boats are rigorously engineered; they don’t just happen. All design decisions I’ve made have some justification, objective or subjective. My background helps engineer these boats for these uses, and they are very qualified for their intended purpose, cruising. Even the 27 has gone offshore safely. Formal training and my family culture contributed, my father and father-in-law worked at Pratt & Whitney, and at home we always did things in a very thorough manner. We built and fixed stuff around the house, and I got a hands-on perspective on building and maintaining things. For example, at McDonnel-Douglas I always made sketches in addition to blueprints of assemblies to help guide workers. A formal drawing can be pretty intimidating and it sometimes helps to have a simpler preview done from the perspective of the man who is going to do the work to help him get oriented. The same here. From tooling to shipping, I can do everything that we do here, maybe I haven’t done it in a long time, but I can do it; it helps create a bond with our workforce and I hope, create better boats. I love building things, the candy for me is the designing. But you can’t separate the two. The world is full of products which are beautifully conceived but poorly executed. I can avoid this through my practical boating experience in power and sail and my formal training. The consumer benefits.

GOB: What boats have you built other than for Island Packet?

Island Packet: Into the Sun

RKJ: There were some one-off boats that no one would know about, followed by the Stamas 44 and then the Endeavour 40. I started working in 1974 for Ted Irwin as a naval architect and did some modifications on existing hull models, the 30 and 33, hulls and rigs, keels and rudders, that sort of thing. I worked on modifying an Irwin one-ton racer inspired by Terrorist (not a name anyone would pick today!). Terrorist was a beautifully built aluminum boat that came from California and was fitted with twin bilge boards and internal ballast. She was a very fast boat. Ted was very creative. He loved boats and I loved working with him. There was another designer at Irwin at the time, Walt Scott, and we all became good friends. I’m not an avid racer, like Ted. I’ve raced, but I don’t cut the handle off a toothbrush to save weight, but he might. His motto could have been, “If it won’t break it’s too heavy.” So I got to work on this boat and I like to make models so we sent one to Stevens Tech for tank testing. This eventually became Voodoo (an evolution of Pantera) with hard chines and triple boards — if two are good then three are better — gybing daggerboard, asymmetrical bilge boards, as a one-ton IOR boat. It didn’t dominate the circuit, but it had its moments, it was clear that it had its advantages.

I ran the plant for Ted for two years then went to work for Endeavour, which was an offshoot of Irwin run by some of his prior employees. Endeavour was just beginning in 1975 and they bought the old abandoned Irwin 32 molds to get started. The two firms were sort of joined at the knee, Endeavour buying materials from Irwin and so on, until Endeavour finally became a competitor to Irwin. I eventually left Irwin, on good terms, and I went to Endeavour so I could design boats with my name on them and run the plant. I designed the Endeavour 43 from scratch. They already had developed the 32 and 37, and a lot of people seem to think I designed them, too, but I didn’t. A fellow called Dennis Robbins evolved them. Then came the 40 which became the 42, both of which were of “Miami Vice” TV fame. It was the real home run for the company.

After that, I went on my own to become an independent designer/builder. By this time, I had a family and two babies. I did a lot of small work: rigs, new keel and interior and deck for Watkins, two complete boats for ComPac, and other odd jobs. I did some work for CSY, also an Irwin spinoff. They were charterers, not builders, and I helped them out with some manufacturing consulting because they were having some trouble. They couldn’t sell enough boats or make money. Basically, I told them they weren’t going to make it, they just weren’t very analytical about running a business; as a chartering outfit they knew what they wanted, but it was too late for them. What they really needed was an infusion of venture capital to keep them going until it all became profitable, and it just didn’t materialize.

George Hahn at Prairie Boat Works was one of my old surfboard dealers and promoters at Wave. He was a delightful guy, and he started off with one of his own designs, the Prairie 32. He had some manufacturing concerns, Prairie was a model of how a boat company should be set up but he still couldn’t make it go. He had a beautiful plant, molds, great new designs by Jack Hargraves, but couldn’t operate profitably and didn’t know why. I still had to put food on the table, so I consulted for two different companies, and did some more odds and ends.

I designed the Lightfoot 21 for my own use, and it got written up and received a lot of attention. It was a combination New Haven sailing sharpie and motor launch, I sold it by plans for plywood construction, but there was also a demand for a glass version, so I made the molds and sold 18 boats. I made the first molds in my carport, probably to the great distress of the neighbors, and then I rented a garage and called the company Traditional Watercraft, working with a lot of fellows in town here who were looking to moonlight a few hours a week.

I marketed the boat and priced it with a dealer in mind but no dealer wanted it, it was too unusual. But it was a great boat, lots of fun. When the SORC was in town at the St. Petersburg Yacht Club for the Boca Grande race, I had my Lightfoot with me and we went to see the start of the race. We motored by with the rig stowed inboard, it had an internal motor well. There were five of us in the boat, my family and Walt Scott, a good friend who’s passed on now. Anyway, the whole pre-race huddle aboard Kialoa, that year’s SORC scratch boat, stops, comes over to the rail and starts asking us questions about the Lightfoot. It was a lot of fun, I wouldn’t take it offshore , but it was trailerable and a good bay boat.

I was also consulting, doing odd designs, but I really wanted to be an independent designer and builder. I was making a living but knew I had complete knowledge of how to build production boats. I had an opportunity to buy molds for a relatively new boat from Bombay Yachts, a local company that was being liquidated. It was founded by two guys who left Irwin: Ross James and Chris Petty. One was production manager and one was sales manager. I bought the molds for the Bombay Express which Walt Scott had designed for them as a beamy cat sloop. Chris Petty had always liked that kind of boat and was the prime mover behind its creation.

That concept (a little history here), in ’74 or ’75 generated the Irwin 10-4 while Chris was Sales Manager at Irwin. A cat sloop is beamy for her length and rigged like a catboat but with a bowsprit and a small jib. With a jib you get rid of some of the difficulties of a big cat. In my opinion, once you get over 22- to 23-feet catboats don’t make a lot sense. If Mark Ellis (Nonsuch) were sitting here he might feel differently, and his 26, particularly with the wishbone boom, seemed to work OK, but the 30, in my estimation, was pushing the limits for a variety of reasons. That’s the art part of naval architecture, the subjectivity of boat design. Everybody liked beamy boats, they’re roomy below, have lots of initial stability, are easy to sail, and to some eyes they look right. Chris Petty convinced Ted to build this boat because he initially didn’t want to do it. It was 25 feet long 10 feet 4′ inches wide, and we called her 10-4, it was the days of citizen’s band radio, and we decided to have a little fun with that. The design got modified, Ted’s idea. He wanted to make her into a sleeper IOR rules racer/cruiser. It made her not quite the same boat; she was initially tender and it made her a little harder for the average sailor to handle. Having said that, hundreds were built. She was roomy, inexpensive, and they’re probably all still floating around.

Chris and Ross left Irwin to start Bombay Yachts, they did a 31-foot Bombay Clipper designed by Walt Scott from scratch then bought a Canadian mold and converted a 44-footer. Their last boat before they went out of business was the Bombay Express, they built 16 or 17, and some were sold as unfinished boats because they were winding down. They didn’t go bankrupt, but they had sold out to an investor who passed away, and the business was liquidated. I realized an opportunity was before me and it was a boat I related to, a centerboarder with a barndoor rudder, looking like a Cape Cod catboat with 5-foot 9-inch headroom. This was the parent boat for the IP line, the Island Packet 26.

Alden in the ’30s started designing these cat sloops, and Irwin did the 10-4 in the mid 70s. Petty left Irwin for Bombay, and they built the Bombay Express. It was in production for 9 months before Bombay was liquidated. I came on the scene and made an offer to buy the molds, and they sold them. I was still operating out of my house but I had two friends, Pete Pastor and Bob Folks, who owned a company called Marine Innovators. They were building the Sandpiper 32 and the Beachcomber 25, but they also were a tooling company and they had made the plugs and molds for the Bombay Express so they were familiar with it. I redesigned the interior and rig, left the rudder as is, put in a different centerboard, and introduced it as the Island Packet. I incorporated formally as Traditional Watercraft, Inc. in the fall of ’79. We built 16 boats over a year and a half; we were able to estimate the pricing fairly well and sold the boats with classified ads in magazines. Our pricing guesses were spot on, and we sold the first three sight unseen, staged payments, owners never seeing them until they were delivered to their doorsteps.

GOB: That’s remarkable, what motivated them to take a chance and buy the boat?

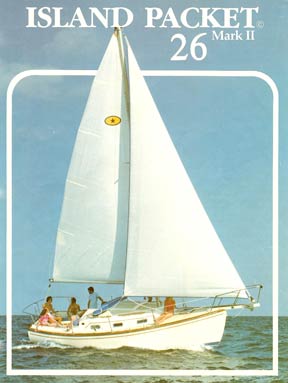

Island Packet 26 Mark I Brochure

RKJ: I did a very thorough brochure, talked to them a lot on the phone, and I knew the boat backward and forward so I could answer their questions. I guess they were comfortable with who I was although they had no reason to be, God love ’em, I couldn’t have gotten started without them and their confidence in me. Their payments financed the construction. Dick Watts of Massachusetts bought the first boat, I built it for a year and a half under contract with Marine Innovators. At that point, the Beachcomber 25 was becoming a pretty popular boat for them, and they couldn’t produce enough of them. I was selling more and more so I realized it was time to take the big step. I rented 4000 square feet, hired five people and started building in-house. I had the glass parts built by one company, the wood parts by another, everything came in ready to put in the boat. Spars, hardware, the same. I built up to about hull 30 then came out with the Mark II, with more headroom, the first Full Foil keel (the original 26 was centerboard and only drafted 2 feet 4 inches with an outboard rudder). The first Island Packet Mark II (not the 26 Mark II yet) was introduced at the Miami boat show in February of ’82 and was bought and called Bubbles. Everyone around Dinner Key seems to know Bubbles; she’s still going strong. (She won the Miami-Key Largo race earlier this year). This doubled our market interest with keel and centerboard options although our business was 90% keel, the rest shoal draft. We built that boat through ’82 and ’83. Then we developed the 31 through the spring of ’83 and in the fall introduced it at Annapolis. I was going to call the 31 the Bermuda Packet or something similar, the company name being Traditional Watercraft, but we went with the name Island Packet 31 because of the name recognition we had achieved. Retroactively, the first two boats became the 26 and 26 Mark II in the fall of ’83. In ’84 we released the 27, which was actually a Mark III 26. The 27 eventually wound up with 6-foot 1-inch headroom by increasing the freeboard. The 31 was the “do or die boat,” I bet everything on it, financially and emotionally, and it was a completely new boat, from the ground up, not an evolution of an earlier design. We sold a lot of 31s right off the bat, it must have hit a nerve in the market. It had an aft cabin with a foldaway door and an articulating chart table, she was a good boat that was both roomy and a good sailer.

GOB: Was this a coastal cruiser?

Island Packet 27

RKJ: There was a battle in the early years: are these or are they not bluewater boats? They weren’t designed as rigorously as they are today, but nothing was done casually: scantlings, laminates, stability calculations – what constitutes a safe stability range – they were as good as anything in the industry at the time. In the ’90s I wound up working on an international stability standard for sailboats when the European Union decided on CE standards for all products, cars, film, cigarettes, everything. They created an International Standards Organization (ISO) effort and the National Marine Manufacturers Association asked me to participate. It took 8 years to hammer one out. It meant going back to the roots and fundamentals of naval architecture and marine engineering, what do we know, think we know, what don’t we know, what do we really know. We came up with, I think, the first holistic approach to a stability assessment for a boat. Our 27’s performance and history is well documented and was one of the validations of this assessment. We studied boats that had gone through “stability events,” one 27 free-fell off a wave on a passage to Bermuda and then rolled over; it took the rig right off of her, (not good) but it righted, even without the rig.

You need to have some weight aloft for resistance to capsize, galleons used to hoist cannon into the rigging in bad weather and beam seas, so light-weight rigs aren’t necessarily a good thing for cruising although they’re certainly useful for racing. The 27 was right on the cusp between Category A (the most seaworthy) and B and today only a few tweaks would be necessary to make it Category A.

All designers have their own standards, particularly for stability, but people couldn’t agree, especially the French, because they design extreme boats; and that is not a criticism of them, it’s a compliment. You also have to factor in that often it’s the mariner’s skill that helps keep a marginal boat afloat, so we had to quantify stability empirically, from actual histories and records. There’s a lot of science involved, but a lot of interpretation, too. When assessing something as complex as a motion of a yacht in a seaway you have to rely on real world experience to develop a numerical rating. This number is the result of a formula, a composite of 7 factors or variables, and we compare this number with documented events. Actual incidents are used to adjust these variables and assign a category based on that number and actual stability statistics. All of my boats now rate as Category A, certified for ocean use.

Competent designers usually find their boats already meet these requirements but in Europe you have to certify that your boats meet these requirements and you must publish them. It was an international work group and the numbers that came up already correlated with boats of known good performance. Island Packet meets these considerations. But you don’t work backward from the rule, to a design. You evaluate the design according to the rule. After all, you can create abberations just to beat a rule, IOR did that, and they have been disparaged for it. All my design work wound up as Category A, and I wouldn’t be surprised if most reputable designers specifically designing for real ocean use would meet the standard already without deliberately trying. We’re known as “America’s cruising yacht leader,” and our boats have nicely complied with those standards.

GOB: What is it about Island Packet that makes them an expressly offshore boat and that makes them different, that defines the niche in the market that you feel you fill competitively?

Island Packet 26

RKJ: In a word, cruising. Quality, safe, dependable cruising. A good turn of speed but not built with that focus. All boats are compromises, and that’s what we favor. Our motto is “First in cruising.” We improved the cutter rig, employ roller furling on all sails, a Hoyt Boom staysail, and a full keel in profile only, that is, a long fin keel, not a wineglass section. All the ballast is in the bottom of the keel — very low and elongated and internal with a low center of gravity. It acts as a backbone to the yacht and adds strength. One fell off a jacknifed trailer at highway speeds and skidded along an Interstate highway and survived with only minor damage. It was essentialy intact; you could have sailed it away.

The keel is something that’s at the heart of an Island Packet, it’s something I’ve never wavered from. It’s been noted that we’re the only full-keel manufacturer although I prefer to think of it as a fin keel that’s morphed to a long fin keel, not a full keel morphed down to what we have. I call it a Full Foil Keel. It’s a 6 1/2 to 7 percent thickness airfoil, which is relatively thin with a modest amount of frontal area for its size. It’s thick because it’s so long, but water doesn’t care; it’s going around a relatively slim blade. We have all the ballast down low and a nice sump for any bilge water to collect in. One of the major advantages to it is that the keel is not fastened to the boat, it is part of the hull, everything is internal and the ballast is capped so we have a double bottom. You could take a chain saw and remove all the glass around the keel and nothing would happen; you’d still have full watertight integrity. You don’t have to have access to keel bolts so tankage can be placed under the sole, below the waterline in the middle of the boat, adding to stability. The tanks are heavy when they’re full. And whether they’re full or empty it doesn’t change the trim much. With no keel bolts you don’t need to have access to them; they don’t need to be periodically tightened. In the event of a hard grounding you don’t have to worry about all the shock being absorbed by a handful of steel bolts, leading to leaks or even structural failure.

The ballast fits inside the keel, and keel and hull are molded in one piece with the ballast ingots — lead or iron in past boats — but mostly lead now, secured in place with cement and resin. The keel is part of the hull, molded in one piece, the angle between the hull and keel is actually a radius, not a right angle, reinforced inside with a series of floor timbers (the garboard on a wooden boat, this is a highly stressed part of the hull) and we have double overlaps and local reinforcement there. One of the things that’s hard to quantify, but easy, I think, to appreciate, is that a hull in a seaway is subject to a variety of motions and forces as the turbulence of this heavy, viscous fluid (water) acts on it. These confused motions reach way below the surface, and a long keel tends to average out and damp these loads in a way a fin keel and a separated rudder cannot. Fin keels give you a much livelier boat, and if you want to go racing, engage in tacking duels and such, that’s exactly what you design for, but you pay a price for that attribute. There are ways to mitigate this but, in general, every effort to shorten the length of that keel is going to require either more draft or more control. You want a boat that’s easy to steer for long periods of time so your autopilot doesn’t have to work its lungs out to steer a straight course. And a cruising boat wants to be able to sail itself without a lot of work. And you certainly don’t want it to broach. Cruising sailors like the wind over their shoulders, and that’s when you have quartering or following seas. You don’t want a cruising boat to get easily knocked off course or broach and roll over.

GOB: Every boat is a compromise. What’s the price you pay for these cruising virtues?

Island Packet 26

RKJ: More wetted surface, and slightly slower response to the helm. It’s like comparing a Corvette to a Chevy Surburban. If you want a hot rod that surfs off the waves and does 15 knots, that comes with a price. But in your more conservative cruising boats with a large capacity for stores and fuel, the price you pay for stowage, accommodations and so forth will impact performance but still in a pretty minor way. The proof of this can be measured by numerous Island Packet offshore race victories often competing against “performance-oriented designs.”

GOB: I imagine that one of the factors you consider in design is accessibility, that is, how easy is it to get to critical points for maintenance and inspection, providing room to maneuver tools and for replacing parts and moving things around. Could you comment on this?

Island Packet 31

RKJ: Having built boats, owned boats, and sailed boats my whole life, I do give this a lot of thought. Also, being a guy who’s over 6 feet tall, I design around my own stature. Most people who walk around in an Island Packet are pretty comfortable no matter what compartment they go into because I’m comfortable when I go there. People who are a lot bigger than I am are probably already resigned to the fact that the world is too small for them anyway. There is an important ergonomic element of getting to things, sleeping in a bed that’s comfortable, room to turn a wrench, and so forth. Of course, if different people designed a boat, a fiberglass laminator, a woodworker, a mechanic, each would get a caricature of a design that reflected their priorities. Every designer has to balance these extremes as best he can. You’re going to have to get the engine out of the boat someday, you’re going to have to change the oil much more often, and so on. But sometimes making it real easy to replace the water pump means you can’t have a nice nav station next to the engine because it’s in the way. Those are choices you have to make on every boat, but we do try in every case to make everything as accessible as possible. It’s for safety too. If you have a clogged fuel filter it has to be readily accessible. Ours is mounted right on the engine compartment door where you can’t miss it.

GOB: What are the basic similarities all IP yachts have in common, in other words, what market niche are you aimed at, what is your mission statement, if you like? And how do the different models differ within that mission design?

Island Packet 26 Mark II Brochure

RKJ: In a phrase, safe cruising boats. It’s hard to quantify or reduce to a sentence, but they all have an identical philosophy. Full Foil keel, cutter rig, geared steering system, laminates, chain plate installations, and spar geometries that are suitable for the same uses. The old 26 and the MK II today might be called a Category B boat, but with only minor modifications, such as to the companionway opening, they could easily be Category A. If you were contemplating a trip to Ireland, I would suggest the bigger the boat the better, all other things being equal, size DOES matter. But our 29 made it just fine, 150-mile days under bare poles, they took the northern route. There is no fundamental philosophical difference in anything we build other than size and cockpit location.

GOB: I’ve noticed that you currently have four models in production, all roughly the same size, in spite of the fact that your firm has had a history of manufacturing yachts of a wide range of sizes. Is there a particular reason for this?

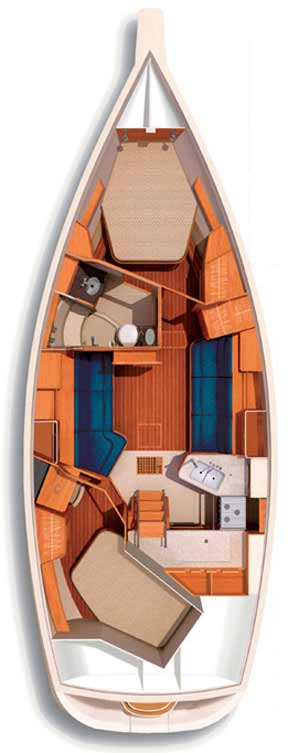

Island Packet 370 Floor Plan

RKJ: That’s true, but most buyers would realize that there is a quite a distinct difference between those yachts besides their size. In the house vernacular, you’re looking at two bedroom, one bath, two bedroom, two bath, etc. Our 370 is a two-stateroom, one-head boat. The 420 has an additional head. The 445, which has just been introduced, is similar, but it’s a mid-cockpit boat which alters the entire interior layout. There are those who love it and those who don’t . . . who prefer the traditional aft cockpit. We build them both, and we don’t care which you prefer, we have one of each. The 485 is a three-stateroom, two-head arrangement. Those are the division points. Could we build a 42-footer with three staterooms and two heads? Sure, but as in building a house, it comes down to how many bedrooms and baths, how many square feet. It determines whether each stateroom is going to be small or big, and we have ideas on how big a stateroom should be, plus we have to factor in a saloon, a navigation station, a galley, and so on. The French, not too many years ago, would build a boat with four staterooms and one head, and that was OK with them, but that’s not the American style. I’ll grant you our sizes don’t sound very far apart but from a marketing standpoint they fall into very distinct niches.

GOB: As far as their overall mission and design characteristics, do they all follow the same philosophy? You’re not specializing in a specific performance market, for example, one isn’t a cruiser/racer while another is an Arctic explorer?

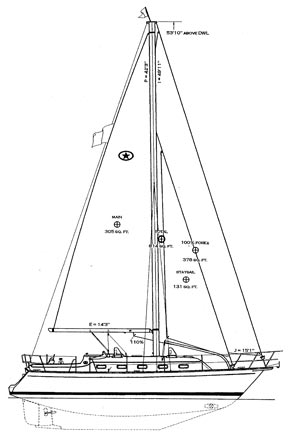

Island Packet 370 Sail Plan

RKJ: No, they’re all offshore cruisers, but they’re equally suitable for just sailing on the bay. They’re comfortable, fun to sail, and easily handled by just a couple, which is an important consideration for us. We want Mom and Pop to be able to go sailing together without needing anyone else. Everything is set up for that and it’s getting easier and easier. We have roller furling, main and foresails roll right up like window shades. Bow thrusters are available on all models, and they’re wonderful. Almost everybody puts one on, it’s like having power steering. It’s powered by a little 7-horsepower electric motor. The ease of handling for a couple, the ability to handle pretty much anything that might come up, safety, quality, and manufacturer’s reputation are all a high priority. Performance is on the list, too, but it’s never Number One. Having said that, we’ve had a number of owners who have gone racing. I’ve done two Annapolis-Bermuda races in Island Packets. In the second we took first in class and second overall. One of our more recent ads list a lot of the Island Packet victories, and just recently, our 420 won the Isla Mujeres race. Most of our owners are not avid racers, they’re eminently qualified to take their boats anywhere they want to go, but they’re not looking for that last 2 percent of performance you need to race successfully or the two-tenths of a percent you need to win consistently. To me, sailing has always been a wonderful escape and release from everyday life and racing, especially if you’re on a keenly campaigned yacht, can sometimes take the fun out of it. I build boats for my philosophy, an Island Packet is first and foremost a cruiser. I like boats that are fun to sail, and it sails very well. If people like to sail and want to go cruising, Island Packet will be a great boat for them.

This performance thing has been beaten to death. People are being sold carbon fiber, they’re being sold epoxy, Kevlar, you name it. First of all, your local boatyard may not have access to these materials, and if they do, they probably don’t know how to work with them. Our boats are literally all over the world, we have a host of circumnavigations, and we make practical choices in design and construction based on the fact that our boat may have to be repaired somewhere very far away where materials, facilities, and skills may be hard to come by. We don’t go overboard with this, but we try to keep it in mind.

GOB: You currently offer four successful models, all with roughly the same mission. On the other hand, your literature lists many different production lines, now discontinued, all with an average build cycle of about five years. Are these evolutionary steps, have you gotten everything out of them you can and you’ve moved on to something else? Or are they driven by market conditions and reacting to them?

Island Packet 445 nav station

RKJ: Both. It’s like any other consumer product. Some builders will build the same boat for 20 years. We have a dealer network that goes from Seattle to San Diego, Maine to Florida, Great Lakes to Gulf Coast, 20 in the U.S., and we have dealers in Europe and Australia. They need — for their and our business to be viable — a continuously evolving product. People want the latest improvements, and we see the need for hidden changes in construction materials and techniques. We’ve just introduced a new model, the 445, and it’s exactly how I want it. Five years from now I’ll have a list of changes two pages long I’ll want to make or that the customers have asked for. A lot of these things get incorporated into the boat during its production cycle. Our Island Packet 35 was introduced in ’88 or ’89, and I remember being asked back then what would I change on it. That boat was everything I thought a cruising boat should be, but in five years we evolved that boat considerably. We put platforms on the stern, we made changes inside that people had expressed an interest in and construction technology changed: we’ve gone from woven rovings to knitted fabrics, amongst other things. After five years, and one or two hundred boats, the first owners start thinking about moving to another yacht and they may have informed ideas now on exactly what it is they want in a new boat. We start to get impacted by our own success when we find a used Island Packet current model on the market. Five years down the road, those same models, maybe with a few evolutionary changes, start competing with our new boats for sales. Five years is a good run for a boat, could we go 10? Sure, but we factor in the effect of the used boats on the market, and in five years we learn a lot about what the customer wants and about what we can do.

Fifteen years ago we were having discussions about whether roller furler jibs were appropriate for cruising. But we’ve made it standard over the years, first the jib, then the staysail, and now the main. The main furls right into the mast, not the boom (we don’t think all the bugs are out of that yet). You pay a small price in performance but no battens, no reef points, no problems. We gave it a lot of thought and told our spar manufacturer that if there were any problems he would have to replace them, but we’re still doing business with him. An occasional buyer wants a standard rig, so we sell it to him. We have a Hoyt boom on our staysail (so named because it was designed by Garry Hoyt), it’s sort of a club-footed boom except it pivots at the forward end, it is self-vanging and self-tacking and adds a lot of power and simplifies control for the staysail. We have 2,000 boats out there today and a very active and vocal group of owners, we have a newsletter, there are internet news groups, numerous rendezvous. People keep in touch with us and help us evolve the boat. We know what our customers want.

GOB: What parts of your boats do you sub out to contractors?

Island Packet 485

RKJ: Spars, sails, cushions. We do all the glass and woodwork here. In the early days everything was subbed out, we just assembled the components here. Glasswork and woodwork were done by separate firms. We brought the mill in-house and the same firm that worked for Hutchins, Arjay Industries, did glass work for us. I wound up buying the assets of that company, it was right across the street, and I brought it all over, people, equipment, everything . . . and he got out of the lamination business. Our glasswork was overdue to be brought in-house, from the standpoint of the type of control we wanted to exercise over it. Bob Cottrell, owner of Arjay Industries, was not your basic glass business owner, he was a Harvard MBA and a chemical engineer, and he took a very methodical approach to fiberglass construction. One of the things he developed was a spray core decking material that eliminates foam or balsa or plywood. You get the Oreo cookie concept of glass, lightweight filler and more glass. We won’t use it on the hull because it reduces puncture and impact resistance, but it makes for a very stiff, lightweight deck. On the hull we use fiberglass, one laminate after another. We bought that technology also and brought it over as well. So we have a 10-year warranty on our deck against rot or delamination. No one else can do that, balsa and plywood core decks will eventually deteriorate. Some other companies do spray core also, but I don’t know who they are; but there is a company out there that sells a similar process (ours is a home-built process, internally developed). If you buy a 15-year old Island Packet, you will not have that core material rot. It can’t. It’s microspheres in resin. It will be just as good as the glass around it.

GOB: Your boats are built in a traditional way, a hull and a liner and a deck. Are there variations or fundamental construction differences in the different models?

Island Packet 35

RKJ: No. They’re pretty much the same. We have a big commitment to tooling, we have a fiberglass liner on the deck, nothing to rot, no fabrics or plywood. That’s why our boats hold their value so well, you can find a 1991 35 for $120,000 or so and that’s what it cost brand-new. It’s one of the reasons we’ve gotten two Best Value awards from Cruising World because when you go to resell it’s going to sell for about what you paid for it. We also have a three-year warranty; no one else does. The cost of ownership, especially in that three-year period, is probably as low as anything out there. You can’t buy a new Island Packet for under $250,000-$300,000, and there’s a lot of good used ones out there more reasonably priced. But keep in mind, if you’re going to do anything more than just run around the bay in it you need to know that boat’s history and inventory it carefully. A 10-year-old boat is probably going to need some work on the engine, sails, rigging, the electronics, it will need extensive refitting for cruising. You aren’t going to be able to match the retailer’s ability to purchase materials and parts, and it’s going to cost you time and money. In the long run, it may wind up cheaper to just invest the money in a new boat, get that peace of mind and warranty and when you’re done sell it and get part or all of your money back. It’s like buying a house, it’s a good investment because you can enjoy it everyday, as long as you’re not house-poor and can’t afford a pair of socks. So a used boat may end up costing more than you think. We’re in the new boat business, I had to put that pitch in there.

Island Packet 35 interior

If you really want to understand something as complex and multifaceted as our company, you really need to talk to Island Packet owners. There’s an Internet chat room. It’s been a very positive thing for us because our owners are so supportive and enthusiastic. We sell more boats through word-of-mouth than anything else we do, and we spend a lot of money on advertising and boat shows every year. Our used boats and our owners say more for us than anything we could say for ourselves. We have rendezvous where we get together, and they’re great! They’re not just polite, they genuinely enjoy their boats. It’s not a hammer-the-factory session, they’re out having fun. They’re a fabulous array of people, company presidents, corporation executives, retired schoolteachers . . . and they have a fabulous history. The boats are cruised widely, and they have a background to them that they share on these rendezvous, the newsletter, and the chat room. The British have embraced our boats . . . after 12 years of getting our foot in the door in the UK through boat shows and so on. And now we’re a household name in the marketplace there, and we’re doing very well. A declining dollar helps, but a lot of other things have gone our way as well. We have a great dealer there, and their economy is doing well. They were our largest dealer in 2004.

GOB: A final question, one I hesitate to ask but which I would be remiss if I didn’t. It’s my understanding that you were involved in a legal controversy with Cruising World concerning some reviews of one of your boats. Could you elaborate on this?

Island Packet 611

RKJ: That’s ancient history now and has long since been resolved. That had to do with a disparaging remark by a Boat of the Year judge about our stability, an unqualified and incorrect assessment, a broad brush, “I think this boat may not be suitable . . .” comment. I paraphrase, of course, that’s not exactly what he said. It was so unfounded and misinformed, I sued them. I’ve got my entire blood, soul, and financial future wrapped up in this business. You can’t make incorrect, flip comments like that without consequences. I thought long and hard about that because I was good friends with the editors in those days, Bernadette Bernon and Patience Wales of Sail magazine, (both retired now) and still am, but I took the magazine to task, and we resolved the issue and I made my point. It’s been a long-term campaign of mine that the magazines be more technically competent, more sensitive to the power of the printed word, and more communicative with the boat building industry, not a self-appointed boat police. I’ve written the magazines as many letters about reviews of other companies’ boats as I have about ours. It’s almost as if the sailing press has a mission to find critical comments to validate some of their reviews. There seems to be an adversarial position often taken in boat reviews. I think they’ve improved a lot now, but I still am a bit of an activist in this area. I returned one Boat of the Year award that we won because the review was so unflattering, and we had won! It’s strange, in powerboat magazines it’s all flowers and candy; you read sailing magazines and they question your competence.

GOB: Bob, we’ve been talking for two hours now and I’ve collected an enormous amount of material, and I know you have other commitments. I would like to thank you very much for your hospitality and your time.

RKJ: It’s been a pleasure, Henry.

Island Packet Yachts 1979 Wild Acres Road Largo, FL 33771 727-535-6431 info@ipy.com

IP Home Port Devoted to Island Packet owners and owner wannabes

Island Packet Yachts 1979 Wild Acres Road Largo, FL 33771 727-535-6431 info@ipy.com

IP Home Port Devoted to Island Packet owners and owner wannabes