Fill your water tanks the natural way

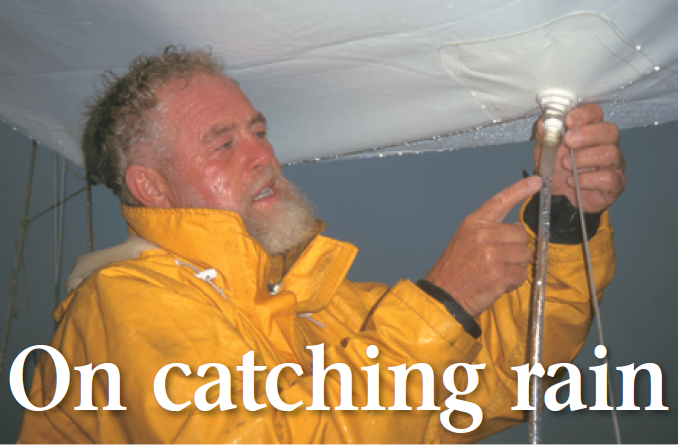

Larry Pardey secures hoses to the small through- hull fittings he and Lin have inserted into the four low points of their sun cover. He leads these to their water tank fill ports. At sea, they invert their mainsail cover under the boom and use it to collect rainwater as it runs down the mainsail.

Larry woke me during the morning off-watch with a shout: “It’s raining!” He struggled into his foulweather gear, and I soon heard the sounds of the raincatcher being tied in place. I looked out the companion- way and saw only a slight drizzle. But when I awoke three hours later, Larry told me he’d caught 3 to 4 gallons of fresh water. Once again we laughed about the eight years we’d spent experimenting with all sorts of ideas for raincatchers, until the day Larry came up with the obvious solution.

He tied our mainsail boom cover under the main boom where it acted like a rain gutter, catching almost every drop that ran off the mainsail. Larry sewed a rope grommet into the part nearest the mast, and we insert a short hose into the grommet (see Figure 1 on Page 31). During a tropical squall lasting 15 minutes we’ve caught more than 35 gallons of water. The raincatcher is also handy because it can be left in place on any point of sail, as long as the winds don’t surpass 25 or 30 knots.

It has been almost 26 years since I wrote the above paragraphs as we reached along between Japan and Canada on board 24-foot 4-inch Seraffyn. I had spent many pleasant hours during that often-stormy passage keeping a log that eventually turned into the first edition of The Care and Feeding of Sailing Crew. The same raincatcher system now works for us on board 29- foot Taleisin. We’ve seen several others that could work for your boat.

During our cruising years we’ve seen and tried several different rain- catchers and found they all fall into three categories: deck collection systems, sun-cover systems, and sail or mast systems. As you look over your boat for potential rain collection ideas, keep the following ideas in mind. First, a well-thought-out system can augment your regular tankage. If you have a watermaker, it can help conserve fuel and engine running time. It can cut down on the number of trips you need to take to the fuel dock for fresh water. It can let your crew shower more often, wash clothes on board, and generally be more relaxed about one of the irksome aspects of life afloat: control of water usage.

Since the system will only be used when there is a chance of rain, it should be unobtrusive, yet easy to set up quickly. At sea, an efficient rain-catcher should work while the boat is heeling, tossing spray. If the sails can be incorporated into the at-sea system, even the condensation of fog or mist can add a bit to your water supply.

In port, any system you design should be workable in fresh winds. Rainsqualls around tropical islands are often preceded by Force 8 or 9 gusts. If you have to lower and reset your collection system for each squall, chances are you’ll say, “The heck with it.” So the best solution would be a catcher that can be set in place and left unattended for much of the time or a combination of systems which work in varying conditions.

Finally, only if I were on board and able to taste the water running out of the collection hoses, would I feel good about letting it drain directly into our main water tanks.

Cabintop collector

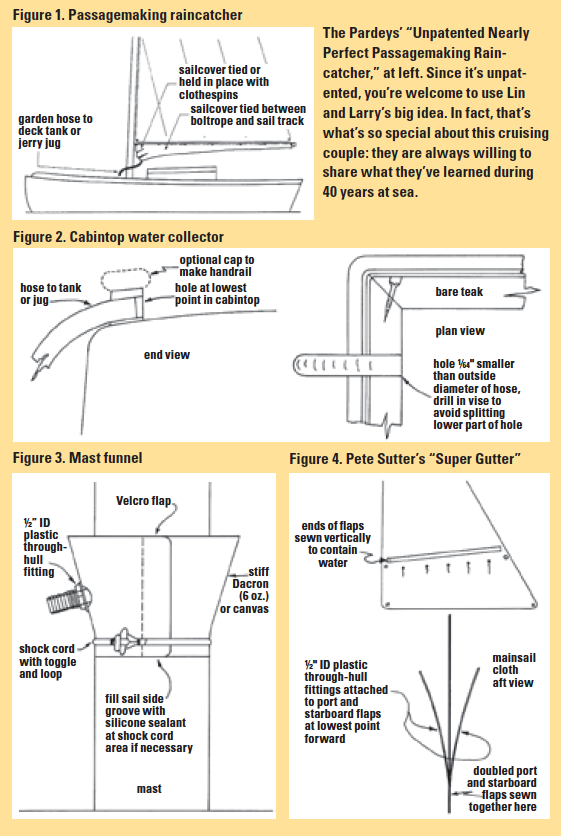

One of the simplest systems we’ve seen is a cabintop collector (see Fig- ure 2 on Page 31). On some English cruising boats, the grabrails or cabin trim are modified to act as a rain gutter along the whole length of the cabin. At the lowest point on port and starboard sides, a hose is jammed or screwed tightly into the wood. At sea, a length of hose can then be led from either side to a plastic jug to collect water on calmer sailing days.

In port, hoses can be inserted in both sides and, once the water is tasted, it can be safely fed directly into your water tanks during heavier rainfalls. A few cruisers we’ve met propound what sounds like an even simpler system, blocking off the scuppers in the boats’ toerails or bulwarks and letting the water that gathers on deck flow directly into the open deck fill plates. With this system, there is a real risk of contaminating your water supply with bacteria and dirt carried on board by guests and crew. The thought of the bacteria that cause athlete’s foot, plus the shore dirt carried on by even bare feet, makes this system seem less than tasty.

Mast funnel

Another very simple, easy-to-con- struct system is a mast funnel (see Figure 3 on Page 31). As the funnel skirt can be unobtrusive and not affected by wind, it can be left in place whenever you wish. To collect the amazingly strong stream of water that runs down your mast once the rain sets in, you need only a semicircular skirt of stiff canvas and a piece of shock cord plus hose to reach either a jug or your water tanks. As a temporary or trial mast collector, you can wrap a short piece of half-inch-diameter line around the mast just above the gooseneck, secure it together lightly with a lashing of twine, and then let the end dangle into a funnel. The funnel will guide enough water into your waiting jug to encourage you to build a more efficient mast catchment system.

Sail-based systems

Sail-based water collection systems can be the most efficient choice at sea. But they only work in port if there is little wind or if the sail used is a riding sail. We’ve seen several different methods of catching the water that runs down a mainsail. Pete Sutter, a veteran San Francisco racer/sailmaker turned offshore cruiser, showed us the simplest sail-based system we’ve seen, one he used on his Wylie 37, Wild Spirit (see Figure 4 below). He stitched a double layer of fabric along both sides of a mainsail seam, just above the first reef. The flap was tacked in place along the upper edge to produce a water trap that funneled rainwater forward to a small, half-inch inside-diameter, plastic, through-hull fitting. This system worked well even during fairly brisk sailing conditions as salt spray rarely reached the area above the first reef. For boats with high booms, it might be best to secure the flap below the reef points to take advantage of as much area of the sail as possible.

Sailcover works too

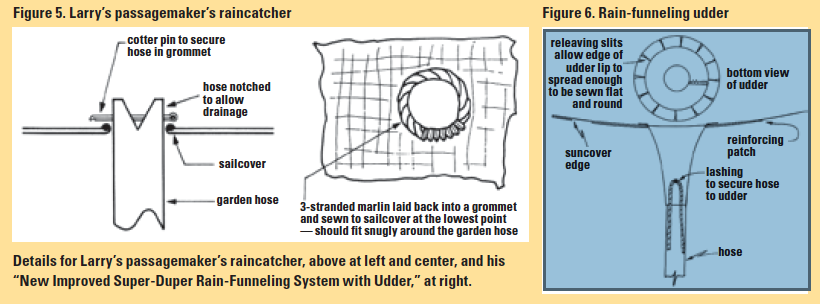

Only slightly less simple is the system Larry invented during our 49- day voyage from Japan to Canada on board Seraffyn. He turned our mainsail cover upside down and secured it to form a trough under the boom. His trough caught almost every bit of water that rolled down the sail and then funneled it forward to a reservoir area he created by lacing the head of the mainsail cover securely.

As we sailed closer to Canada, he added one simple modification that helped us arrive in port with full water tanks. He stitched a grommet to act as a hose holder at the low point of the reservoir (see Figure 5 on Page 32). What amazed us most was that during days when fog obscured the horizon, we caught up to 3 gallons of condensation during each 24-hour period. We liked this system and had the people who made our new mainsail cover for Taleisin sew a fabric udder into the head area. The udder folds out of sight inside the cover, except when we need it as part of the rain catchment system. Then a hose slips inside and is held by a lashing (see Figure 6 on Page 32).

Andy Peterson, a Chicago sail- maker who is now cruising on his floating sail loft, a 57-foot ex-off- shore racer, Jakaranda, originally showed us the cloth rain-funneling udders on his sun covers. We had him sew similar udders in four plac- es near the edge of our sun cover, once we determined the best collec- tion spots. We found they contributed to an excellent in-port rain collection system. But for any sun cover to be part of a collection system, it must be strong enough to hold up in winds of up to 25 knots. We had to reinforce our cover battens and batten pockets to make this workable. In stronger winds, the cover must be taken down and a smaller cover set in place.

For those with a soft-top Bimini, either udders or a cloth gutter similar to the one Pete sewed onto his mainsail can be secured along the outer edges of the top. This will work in port or at sea.

Spare jugs

Whatever rain collection system you try, it pays to have spare jugs to hold the water you catch. Even though the first runoff from a rain shower will probably produce water that is slightly brackish as accumulated dust and salt is flushed off sails and rigging, in areas where rain is in short supply, this could still be useful for bathing and rinsing clothes. Without spare jugs you’d have to let it run off into the sea.

As you enjoy your first months of cruising, look around and consider these raincatcher ideas. Put on your foulweather gear and spend some time watching the rain flow off your boat the next time a shower or squall comes by. Follow the track of the heaviest flows and think of ways to form a dam or entrapment area. Try rigging a small cover to see how much extra water this will catch. We were amazed to find a 4- x 6-foot sun cover caught 5 gallons of rainwater for us during a 15-minute squall, so the catchment area need not cover your whole boat to be a helpful addition to your supply.

Some people will say, “Why not just add a mechanical watermaker?” But those on small budgets will find a water-augmenting system that works at almost no cost, uses no electricity, and requires little maintenance, means that your budget can be stretched to cover a few more months of cruising. Even those who do have watermakers on board should consider collecting the free rain that falls on board, especially in a tranquil harbor.

These simple devices could take the concern out of any electrical or mechanical failure that shuts down your watermaker. According to the Seven Seas Cruising Association equipment survey done in 2005, of the 156 sailors who had watermakers on board, 16 percent said they had required repairs during the preceding year.

Rainwater catchers could also give your generator a break. This will mean you are doing your small bit for the environment by using less fossil fuel and minimizing noise pollution.

Water jugs afloat

It is difficult to imagine the importance that water jugs assume in a cruising life. If you have spent the majority of your sailing life along the coast of Europe or the United States, chances are you have rarely had to cart every gallon of water you use from shore to ship in a dinghy. But once you set off for long-distance exploring, there will be few dock hoses accessible to deep-draft vessels, and fuel docks where you can lie along- side for top-ups will be rare except for major charterboat areas. So a careful look at jugs before you set sail will have more beneficial effects than you’d first imagine.

For years we used clear hard plastic jugs; we secured them on deck near the shrouds when they were full and under the dinghy once they were empty. Full or empty, they always seemed to be underfoot, taking up far too much deck space, scratching the paintwork if they slid across it, stubbing toes at night, and breaking open if one of us accidentally dropped a full one against something hard.

All the solid jugs we tried, both the cheapest and most expensive varieties, began to crack and deteriorate after a year in the tropics, and no matter how securely we tied them, one always seemed to slip loose of its lashings during a rough beat to windward to bang against the bul- wark and drag one of us forward into the leeward scuppers just when we didn’t particularly want to be there.

Next we tried the clear soft plastic folding jugs we found in a fishing shop. These had definite advantages. We could carry half a dozen folded away in a locker until we needed them. Since they took up little space, we could leave two in the dinghy and grab a bit of water each time we went ashore instead of making a major foray of topping up our tanks.

Additional tankage

The soft jugs conformed to the shape of the bilges and so gave us instant additional internal water tankage separate from our main tanks for passagemaking.

Their ability to conform to different shapes meant we could fill and secure one inside the dinghy where it is stored at sea, so if ever we had to abandon ship in a hurry, we’d have an extra water supply to augment that provided by our reverse-osmosis, hand-pump watermaker. Though these soft jugs didn’t burst or crack if they accidentally hit a cleat or metal fitting, they were susceptible to chafe and cuts where they lay against hose clamps or threaded bolt ends in the bilge. So we took care to store them clear of sharp objects. As with the solid jugs, the ultraviolet rays of the sun turned these jugs brittle if we left them on deck for more than two months in the tropics. But as they folded and stowed below, we could cut sun exposure to a minimum.

We finally found a way to improve on this aspect of jug performance after a chat with a plastics engineer. In his words, “Carbon black inhibits the transmission of UV rays into plas-tics and slows the breakdown of the plastic molecules.” He recommended black plastic jugs such as those used by photochemical companies. We used hard, black plastic chemical jugs for water storage during our last three years of voyaging on Seraffyn. Not one broke down due to UV exposure.

Then, during a shopping trip to a camper-supply store in California, we found a fine compromise solution that has made our tussle with water jugs a far fairer one. Reliance Products Ltd., of Winnipeg, Canada, produces tough black plastic folding jugs, which they fit out to be used as solar showers for backpackers and campers. They are available in two sizes: 5 gallons and 2½ gallons. We carry both sizes on board. The small- er one is easy for a lightweight crew- member to carry, so we can both transport water. This smaller size also takes less space on deck, so we don’t mind leaving one under a rain collection hose even if there is no immediate sign of rain. These jugs seem impervious to the sun and have lasted six years at a time, in spite of hard use both on deck and below as we cruised on Taleisin. And as a bonus, we find we often used them as they were originally intended, for on-deck solar-heated showers after a day of skin diving near the coral reefs of tropical cruising grounds.

The Pardeys’ “Unpatented Nearly Perfect Passagemaking Rain-catcher.” Since it’s unpatented, you’re welcome to use Lin and Larry’s big idea. In fact, that’s what’s so special about this cruising couple: they are always willing to share what they’ve learned during 40 years at sea.

Details for Larry’s passagemaker’s raincatcher, above at left and center, and his “New Improved Super-Duper Rain-Funneling System with Udder.”

This article was excerpted from Lin Pardey’s book, The Care and Feeding of Sailing Crew, which has just been up-dated and released as a third edition.