The world’s most famous physicist was a devoted, if unconventional, yachtsman.

What name would you give an amateur sailor who capsized, hit rocks, and ignored bad weather? Who nearly collided with other boats, refused to wear a life jacket although he couldn’t swim, frightened passengers with his recklessness, and neglected his vessel’s upkeep?

The name would be Albert Einstein. Yes, that Albert Einstein.

Sailing was a passion for the lovable, spaniel-eyed genius with the wild white hair that floated in the wind. He learned to sail on the Zurichsee (Lake Zurich) in Switzerland in 1896 when he was an 18-year-old student. And he continued sailing until old age forced him to give it up on the East Coast of the United States more than 50 years later, at the conclusion of World War II, long after he had become the world’s most famous physicist.

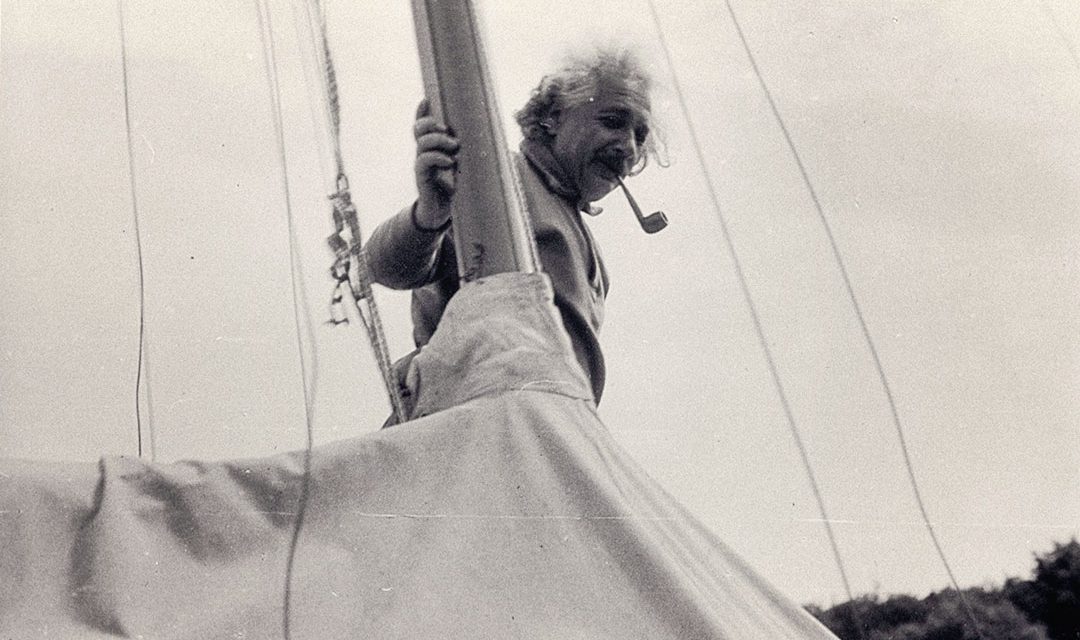

Einstein sailed as he lived his life—absentmindedly. He was a dreamy kind of sailor, a man who was bemused and delighted by sailing. His was a true passion, undiluted by caution and unburdened by technical knowledge. Einstein was an instinctive sailor. A sailor, it is safe to say, the Coast Guard would have hated to see coming.

His mast fell down regularly. He often had to be towed home. He almost managed to drown himself and had to be rescued by a motorboat. He wouldn’t carry an outboard motor himself, though. He despised machines. He’d rather drown, he declared, than permit a motor on one of his beloved sailboats.

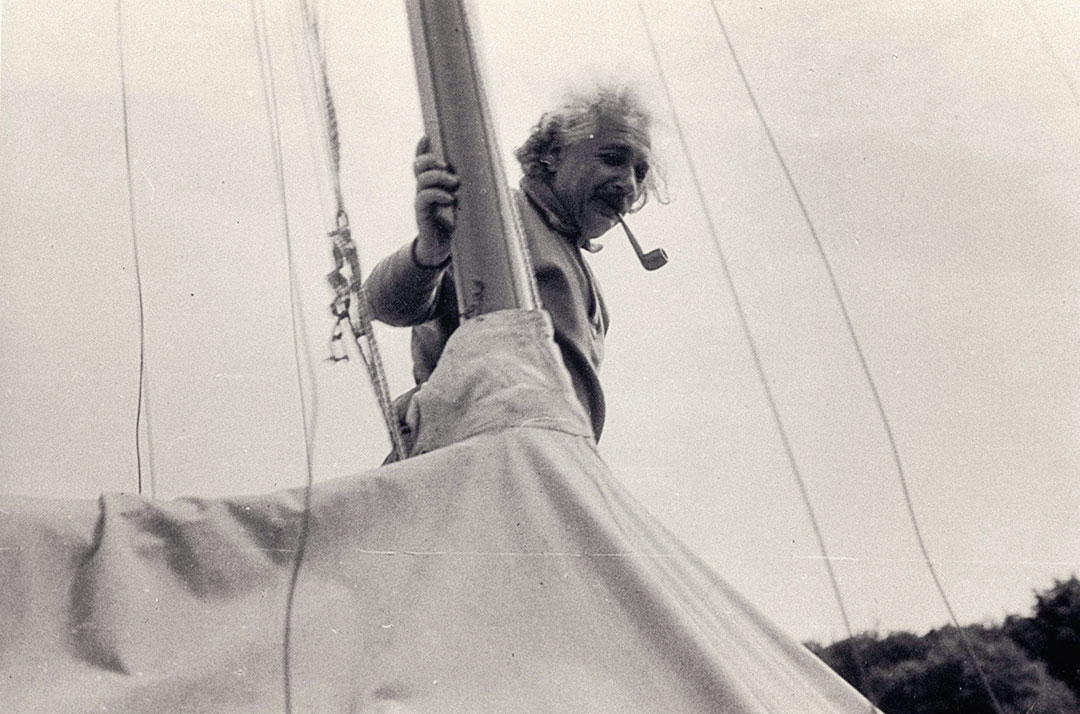

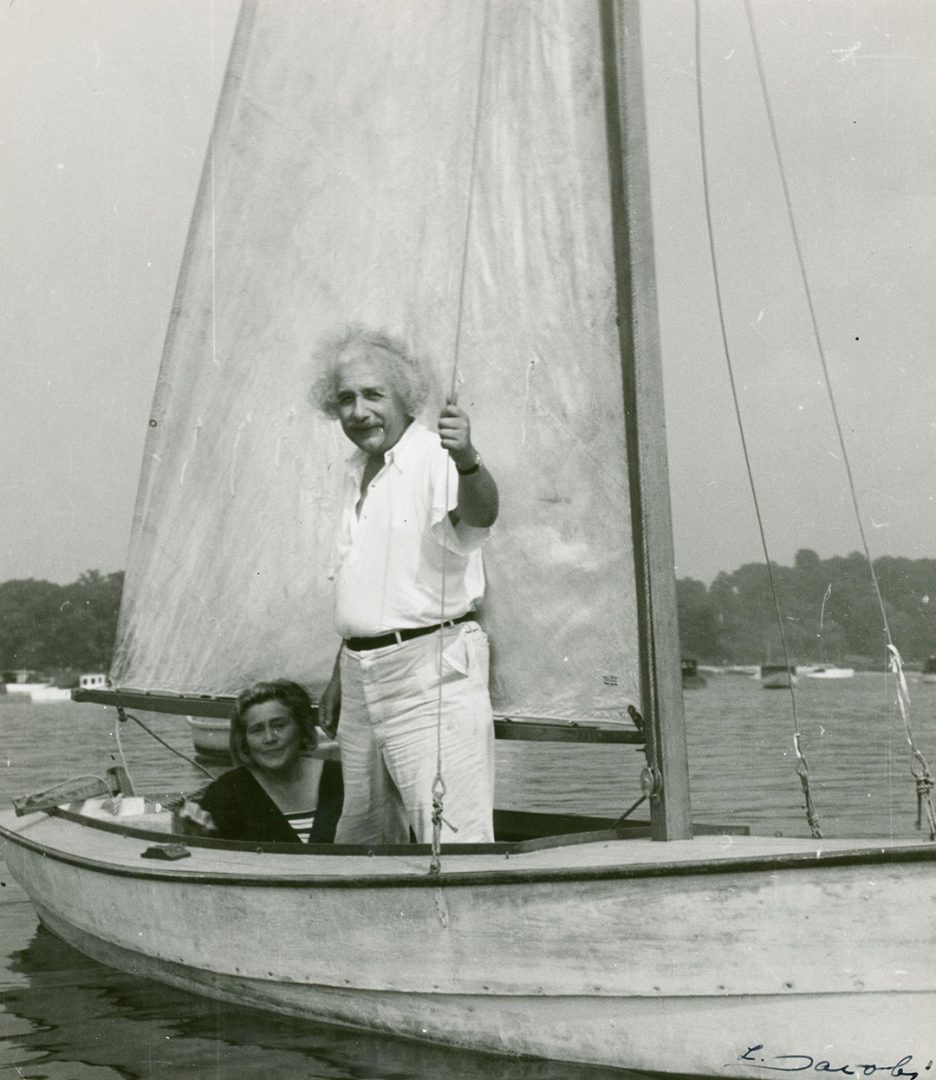

The sailboat in question, one of many he owned or borrowed, was a battered 17-foot daysailer called Tinef—meaning worthless, or of no intrinsic value. He sailed her extensively in New England, though it is difficult to classify, in conventional terms, the type of sailing he did.

He never strayed too far from shore. He certainly didn’t race. His friend Dr. Gustav Bucky, who sailed with him often, said: “The natural counterplay of wind and water delighted him most.”

One might conclude, then, that Einstein was a cruising yachtsman. Of sorts. And relatively speaking, of course. He wasn’t a conventional gunkholer.

When Einstein settled in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1933, he had long been the most famous scientist alive. In 1905, while working as a probationary technical expert (third class) at the Swiss patent office in Bern, he wrote five scientific papers in his spare time. Among them was his first on special relativity. It was a dissertation of 9,000 words, entirely devoid of footnotes or references. It was an extraordinary document from an extraordinary man.

Einstein was recognized as the most brilliant physicist the world had seen in three centuries, perhaps of all time. His great strength was his ability to make intuitive leaps of the mind and then find the scientific facts to fit them. His theory upset classical concepts of physics and laid down a blueprint for the way the physical world was built. And, paradoxically, although the vast majority of people would never understand it, it excited their interest and fascination to the extent that he was mobbed when he appeared in public.

His famous equation, E=mc2, in which energy equals mass times the speed of light squared, became a household phrase the world over.

It is impossible not to speculate on how much of the theory of relativity may have come to Einstein while he was sailing. From the very beginning, he carried a notebook with him on the water. When he was 18, he often sailed on the Zurichsee with Fraulein Markwalder, the daughter of his landlady. It was a lasting friendship, for he was still writing to her 50 years and two marriages afterwards. She remembered that when the breeze died and the sails drooped, out would come the notebook and he would be scribbling away. “But as soon as there was a breath of wind, he was immediately ready to start sailing again,” she said.

Naturally, Einstein would have been as aware as any other yachtsman of the effect of the kinetic energy stored by a moving boat. That formula is described simply as: mass, times the square of its speed, divided by two.

In practical terms, it’s an early form of relativity. It means that hitting the jetty (or another boat) at 2 knots is relatively less damaging than hitting it at 4 knots or 8 knots. If the damage at 2 knots equals $200, then the damage at 4 knots will be $800 and at 8 knots it will be $3,200. (Of course, these fast-escalating figures will neither surprise nor shock latter-day sailors long rendered numb by the prices of everything to do with yachting.)

Soon after he settled in Princeton with a lifetime appointment to the Institute for Advanced Study, Einstein, who was as much of a recluse as a Nobel Prize winner can ever hope to be, taught his secretary-housekeeper, Helen Dukas, how to deal with members of the public who wanted a simple explanation of relativity.

“Tell them,” he advised her, “that an hour sitting with a pretty girl on a park bench passes like a minute, but a minute sitting on a hot stove seems like an hour.”

Despite his grasp of some of the universe’s most profound complexities, Einstein worshipped simplicity and harmony. He loved fields and forests, lakes and mountains, the earth, the sky, and the sea. And when he was sailing, he found simplicity, harmony, and, undoubtedly, inspiration in the rhythms of the wind and the waves.

He also always found his way back home from the sea or the lake, which is more than can be said of his attempts at navigation on land. In his book Einstein in America, biographer Jamie Sayen relates the story of a Princeton undergraduate during Einstein’s first year there:

“Twice I heard from two different girls who lived in Princeton about his [Einstein’s] sense of direction. Each said that Einstein had approached her on a side street several blocks off Nassau Street and asked for directions to Nassau Hall. In each case Einstein explained that the only reason he wanted to get to Nassau Hall was that he knew his way home from there.”

But perhaps the difference between his navigational skills on land and on the water is not so paradoxical after all. As he pointed out so elegantly, nothing is absolute, not even navigation. For instance, during the summer of 1934 spent in Watch Hill, Rhode Island, Einstein on more than one occasion ran aground while sailing with his friend Gustav Bucky. The man who understood better than any other in the world the physical forces that caused the tides never managed to master them. Stuck on the bottom, “While Bucky fidgeted, the schoolboy at the tiller would laugh and say: ‘Don’t look so tragic, Bucky. They’ll wait for me at home—my wife is used to this,’ ” Sayen writes.

The following summer he sailed from Old Lyme, Connecticut. He seemed to enjoy the sense of control sailing gave him. He never mastered any other kind of machinery. He never learned to drive a car, for instance. “It is too complicated,” his wife, Elsa, explained to a visitor. He was well over 50 before he learned to handle a camera. He used a typewriter with great difficulty and mostly wrote in longhand.

In 1939, he passed the summer at a remote spot on Long Island, sailing daily. According to Sayen, Einstein “loved it when the sea was calm and quiet, and he could sit in Tinef thinking or listening to the gentle waves endlessly lapping against the side of the boat.”

But he was just as happy when it was rough. His friend Eva Kayser described one time when she sailed on Long Island Sound with Einstein: “It was a rough sea; I’d rather have bitten off my tongue than to say, ‘Look, this is a little bit rough, let’s turn around.’ He was sailing away, bending down under the boom, and I said, ‘I bet this is one of the few things under which you bend.’ He laughed and said ‘Yes.’ Finally, he said, ‘Well, maybe we’d better turn back,’ and enthusiastically I said, ‘Yes!’ ’’

On another occasion during the summer of 1944 when he was 65 years old, Einstein was sailing on Saranac Lake, high in the Adirondacks, with three companions in choppy conditions. When he hit a rock, the boat quickly filled with water and capsized. Einstein was trapped beneath the water under the sail and his leg had become tangled in a rope. Without knowing how to swim, he managed to free his leg and claw his way to the surface, where he was rescued. Had he panicked he undoubtedly would have drowned.

Ronald W. Clark, in his book Einstein: the Life and Times, comments on two sailing traits Einstein displayed regularly. One was his indifference to danger or death—reflected in such fearlessness of rough weather “that more than once he had to be towed in after his mast had fallen down.”

Another was his perverse delight in doing the unexpected. His friend Leon Watters was once out sailing with him “and while we were engaged in an interesting conversation I suddenly cried out ‘Achtung!’ for we were almost upon another boat. He veered away with excellent control and when I remarked what a close call we had had, he started to laugh and sailed directly toward one boat after another, much to my horror; but he always veered off in time and then laughed like a naughty boy.”

Clark also relates that on another occasion, Watters pointed out that they had sailed close to a group of projecting rocks. Einstein replied by skimming the boat across a barely submerged shelf.

“In his boat, as in physics, he sailed close to the wind,” Clark comments.

Unexpectedly, it was sailing that had given him most concern for his health. When he was 49 and still living in Berlin, he suddenly collapsed one day and had to consult a doctor. He was normally skeptical of physicians, but this one impressed him. Dr. Janos Pletsch diagnosed inflammation of the walls of the heart. Einstein confessed that he often rowed home his heavy yacht when there wasn’t a breath of air to ruffle the waters of the Havelsee, a lake only a few miles from the center of Berlin.

Pletsch put Einstein on a salt-free diet and packed him off to a small seaside resort on the Baltic coast north of Hamburg. Einstein recovered there, but not as rapidly as expected. Finally, Pletsch discovered that Einstein the addict was still secretly sailing and ordered him to put a stop to it.

That didn’t last long, though. On his 50th birthday, his friends presented him with a new sailboat called Tümmler (German for porpoise), which he kept on the Havelsee. He loved her dearly.

“He sails the boat with the skill and fearlessness of a child…The joy with this hobby can be seen in his face, it echoes in his words and in his happy smile,” wrote his son-in-law, Rudolf Kayser, in his 1930 Einstein biography under the pseudonym Anton Reiser. That joy was dimmed, though, when his property was confiscated as part of the national socialists’ seizure of power in 1933, and he lost Tümmler forever, in spite of trying to convince a friend to spirit the boat to a Netherlands boatyard for safety. Tümmler was “perhaps the one thing it hurt him to leave behind when the time came to shake the dust of Germany off his feet,” said Pletsch.

With the spread of fascism in Europe, Einstein became the world’s best-known refugee. He was an instinctive pacifist and a committed Zionist who eventually and reluctantly concluded that force, and even the sacrifice of human life, was necessary to defend the ultimate ethical values on which all human existence is based. During World War II, he worked for the U.S. Navy as a research consultant in the field of conventional explosives. But he continued to indulge his passion for sailing at Saranac Lake and on Princeton’s Carnegie Lake.

He was at Saranac Lake on August 6, 1945, when he heard the radio announcement of the bombing of Hiroshima. He was devastated. Here, in the most tragic manner possible, was demonstrated the proof that E=mc². That formula forecast the release of formidable quantities of energy if the atom were ever split. Now the nucleus of the uranium atom had indeed been split, and the resulting energy had been used to kill thousands of human beings.

“Almost overnight,” says Clark, “Einstein became the conscience of the world.” And as such, he wrote, spoke, and broadcast throughout the 10 years of life that remained to him. He became an internationally respected spokesman for ethical humanism and a symbol of the scientist as the world’s conscience. There was no time for sailing now. And besides, he was getting frail. His wife, Elsa, had died in 1936, and nearly 20 years later he was to follow her. In April 1955, Einstein, the gentle, lovable genius who had forever changed mankind’s perspective of the universe, began another voyage, into the unknown. And a grieving world wished him fair winds and safe landfalls.

In Search of Einstein’s Boat—David Allen

In 2011, a sophomore at State University of New York’s Maritime College in the Bronx jumped into his car and drove 300 miles north to the Adirondacks to join a landscaping crew charged with sprucing up the grounds of The Knollwood Club. The club maybe held a secret, and getting past the locked gate by conventional means to investigate that secret had already failed.

The Knollwood Club was created in the late 19th century on the banks of Lower Saranac Lake to serve as vacation haven for Jewish people, then “restricted” from many hotels and country clubs. In the late 1930s and into the 1940s, The Knollwood Club was a summer retreat of Princeton Professor Albert Einstein—cabin number 6.

Now with the access he needed, the student peeked into the windows of the shed behind cabin 6—empty. He explored the wooded area nearby, he searched under the porch. Nothing. He was looking for Tinef—or possibly the remains of Tinef—Einstein’s boat for many years.

The sleuthing was part of a semester-long school project to research the provenance of an artifact and deliver a publishable paper on the findings. The prospect of learning more about this artifact had just dimmed, and the student returned to Maritime College empty-handed.

But the story wasn’t over. On the final day of classes in the fall of 2014, another student who was working on the “Einstein boat” project received a cryptic message from Rob Furnette, a boatbuilder and river guide with a shop in Tupper Lake, New York.

“I have the boat you are looking for. Here is a photo.” The photo showed a boat on a trailer, parked in the weeds alongside a dirt road.

Could it be?

Earlier that year, Furnette had been contacted by an old friend who told him, “I have Albert Einstein’s old sailboat. I bought it from a long-time tenant at Knollwood. It was old when I acquired it, and if you don’t come get it in two weeks, well… let’s just say I’m going to turn it into kindling. My chainsaw should be back from the shop by then.” Furnette says he quickly bought a trailer and went and picked up the boat.

Though Furnette was helpful and cooperative with the student researchers, they were unable to conclude anything definitive about the boat’s provenance. The design is common, but particular elements, like the bollard and the coaming shape and rake, don’t match known photos of Tinef.

Could Furnette’s boat be a boat Einstein sailed on Lower Saranac Lake? Sure, but nothing confirms that, or that it’s a boat he owned. Other than the number 3 on a moldering sail, there were no markings anywhere on the hull.

More recently, students have uncovered evidence that Tinef was on Princeton’s Lake Carnegie in the late 1950s, right around the time of Einstein’s death, and acquired by the captain of Princeton’s sailing team. After he graduated, he moved to the Seattle area and took little Tinef with him.

And so, the sleuthing continues. This fall semester, a new group of Maritime College students will begin tracking down that part of the story.