Lessons learned while sailing down the East Coast to warmer weather

Issue 151: July/Aug 2023

It’s a long trip south, but beautiful anchorages make it all worthwhile.

You’re ready. You have the boat of your dreams and you’ve spent enough time sailing your home waters to be prepared for the leap south for a winter in the sun. To be sure, it’s a monumental coastal cruising journey that will certainly be a definitive time in your life. But what are the realities and logistics that go into such an endeavor?

My wife, Ellen, and I took our first trip south down the East Coast of the U.S. in 1981 on our newly launched Nor’Sea 27, Entr’acte. We had several years of sailing experience on Long Island Sound, but from the very beginning of our voyage we recognized a fundamental difference between vacation sailing and cruising long distances. Making a boat go and getting it to take you to a faraway destination are two entirely different things: The farther the destination, the trickier things become. The cruising guides cover almost everything. We had them and thought we understood them, but there was much we missed or misunderstood, and as a result, we paid the price.

Most of our cruising buddies from the “Class of 1981” made it to Florida, and many well beyond, but sadly, some dropped out along the way, frightened and disillusioned after an accumulation of bad experiences. Most of these missteps could have been avoided with a better understanding of what they would encounter.

Ellen enjoying a glorious wing and wing run southbound.

I am not about to recap the guides; they do a great job. Instead, I would like to isolate some subjects, misunderstandings, and attitudes that caused the most grief and explain our solutions as our experiences grew over the years. My goal is to help you stack the cards in your favor.

Getting Started

The biggest question is: What’s your destination? “South” is a pretty nebulous place. From the East Coast there are three main destinations: Florida, the Bahamas, and the Caribbean. Each one presents different challenges and each requires the proper strategy. And if you’re on the West Coast, you’re pretty much going to be aiming for Mexico. Much can and has been written about the various routes south, and an article could be devoted to each. For this exercise, though, I’ll stick to the route down the East Coast.

Most first-timers get underway too late in the season. Like playing chess, your opening move determines the game. If you are still on the Great Lakes in September, you are late. If you are one of the last boats to transit the Oswego Canal Locks before they close for the winter, you are in for some very cold and unpleasant runs. That’s one mistake we did not make. We did however, make others.

It’s best to view this voyage as a collection of smaller, more manageable trips. The experience you gain will prepare you for the next run. A reasonable plan would be: In June/July, cross the Great Lakes and head down the Hudson River or depart from the Canadian Maritimes or Maine bound for Long Island Sound. In August/ September, explore the Chesapeake Bay, and in October/November, cruise the Intracoastal Waterway (ICW) to Florida. Then it’s off to the Florida Keys or possibly Bahamas, or if you prefer, just sit somewhere in the sun and watch the pelicans.

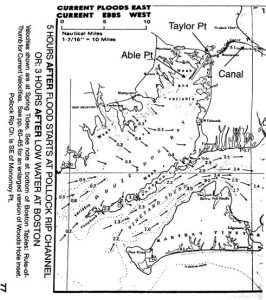

Consult the Eldridge Tide and Pilot Book and plan your transit to arrive at Taylor Point at slack current before the ebb. This will minimize the effect of wind against current. Courtesy of Eldridge Tide & Pilot Book.

Your voyage is going to take time. Until you have made this trip, it is difficult to comprehend the distances involved and the time required to move a boat at 6 knots or less. Accept this and be patient. Don’t rush. Relax and enjoy the adventure. Remember, you’re not driving a floating car; you are taking a boat to sea. All plans and destinations must be made according to the laws and demands of the sea, the seasons, and the weather. To fight the sea and nature is to invite misery, stress, and possibly failure.

One thing you must cure is the “we gotta go” syndrome. Start late and you begin to push it in order to make up time because winter is chasing you and you have to move. The faster you move, though, the more experiences you will miss. Don’t turn your dream into a daily chore, but don’t dawdle. You need to strike a balance, with the goal being to have an adventure, enjoy the journey, and avoid the nightmares. A key to this is: Travel in good weather; stay put when it’s bad. Fortunately, bad weather is quite predictable once you understand what to look for.

Weather

Nearly every destination and decision you make should be based on weather. When we were newbies, our biggest disasters were due to misunderstanding the weather. We learned the hard way that there are two kinds of forecasts — the one we hear and the one we want to hear. Regardless of what the forecast said, we went anyway because “we gotta go!” Of all the gear you have on board, you absolutely must have some way of receiving regular, reliable weather information. During our earlier voyages south we would have sold our souls for internet-based smartphones, tablets, and the profusion of weather apps we have today. But be careful. They are only useful when internet access is available.

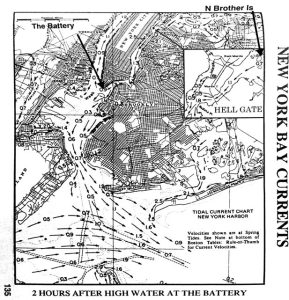

The New York Harbor current chart contains a special inset specifically for Hell Gate. Note the all-important Battery if eastbound and N Brother Island if westbound. Courtesy of Eldridge Tide & Pilot Book.

There is one serious caution regarding weather apps. When you scroll across the time of day to see three-, six-, or 12-hour periods, be extremely observant and make certain that the screen has, in fact, updated. If you scroll too fast, the app might not keep up and can freeze for a few moments. If you notice the freeze, shut off the app, restart it, then make your decision.

At certain points along the coastal route south, you’re bound to lose cell coverage. You need a backup. NOAA’s VHF radio broadcasts will be adequate, but VHF range is limited too. Having a shortwave receiver, single sidebar radio, satellite phone, or other satellite communication device to obtain forecasts and GRIB files are all good options.

Once your weather forecasting is set, now comes two operative words: Cold Front. The guides that go into complex detail to explain them don’t do justice to what this actually means to us on our plastic boats. “A passing cold front” means a strong, very cold wind becoming northwest, shifting north, and increasing in velocity. These fronts don’t appear out of nowhere. If you follow the 24-, 48-, and 72-hour weather charts, frontal passages should come as no surprise.

When traveling south on the Hudson River or sailing Long Island Sound, north winds will provide a great reach in sheltered water. That same wind on the creeks of the Chesapeake Bay is a blast, but being out in the center of the bay in a northerly tempest can be dangerous. You can certainly travel the ICW during or after a frontal passage, but do not cross North Carolina’s Albemarle or Pamlico sounds in those conditions. Follow and track the cold fronts carefully, and figure them into your planning. If any forecast predicts the passage of a cold front, continue inside or stay put. If you go outside, plan short hops to arrive at the next inlet before a frontal passage occurs. If you are outside and hear that a cold front is due to pass, get inside as soon as possible. Again, resist that “we gotta go!” urge.

Atlantic Ocean

Now onto the actual route itself. From Maine to Buzzards Bay in Massachusetts and Long Island Sound, you are in the Atlantic Ocean in every respect. You get it all — islands, wind, calm, swell, waves, fog, rocks, ferries, you name it. Monitor the weather and plan your moves carefully. The sailing experience you gain in this area will prepare you to sail elsewhere in the world.

Once you are on Long Island Sound the ocean swell disappears, but remember that you are still at sea, and under certain conditions the mild sound can become nasty. If you are near Block Island, just south of mainland Rhode Island, and are lucky enough to get a solid forecast for two days of a light northeast wind, you can test your offshore ability on the 160-mile passage to Atlantic City or Cape May in New Jersey. A northeasterly wind in this area is usually a precursor to bad weather.

It can be a delightful trip, but look carefully at the prognosis and pick your entrance inlet accordingly. Cape May is a good inlet to stage for Delaware Bay. We had a delightful two-day run to Atlantic City and transit through the inlet. Then, the day we arrived, a gale began at midnight that rendered the inlet impassible for several days.

Inlets, anywhere in the world, are not to be taken lightly. They are mostly all open to the sea and because they are affected by so many factors, they are not all created equal. The cruising guides cover inlets along the East Coast in great detail. Some are safe; others are dangerous and should be avoided unless you know them well. Inlets tend to break in strong onshore winds. These breaking seas cannot be seen from seaward and you only realize the danger when it’s too late to turn around. Study the guides and take their admonishments seriously.

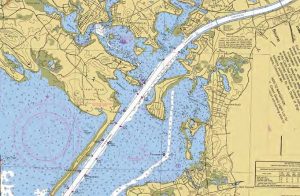

The Cape Cod Canal, a sea level land cut without locks, is easy to transit and well sheltered from the prevailing southwesterly winds in Buzzards Bay. Go westbound only with the current.

Cape Cod Canal

If you’re coming from Maine or points east, you might have been sailing on the ocean for years and not passed through the Cape Cod Canal. From west to east it is actually pretty simple. From Cape Cod Bay going west, however, can be a bit tricky.

The Cape Cod Canal is an 8-mile sea level channel without locks, followed by a 4-mile exit channel into Buzzards Bay. Going with the current, these 8 miles are easy; it’s the next four miles that can be a challenge. When the prevailing southwesterly wind blows more than 10 knots, the water of Buzzards Bay funnels into the narrow entrance channel that runs from Able Point to Taylor Point. On the ebb, the southwesterly wind collides with the west-flowing current to generate a steep, short chop that, even with full power from your engine, can stop you cold. Those last 4 miles can be a wet, hard go until you can leave the channel.

An old-timer gave us this advice: “Arrive, or wait at the canal entrance, until one hour before the slack current before the ebb at Taylor Point. While you wait, put on your foul weather gear, secure everything below, and clear your foredeck of anything that might wash overboard. You want as little current with you (opposing the wind) as possible.”

This might seem ridiculous as you motor along in flat water on a sunny day, but once you turn the corner at Taylor Point, you will be thankful. Of all our westward transits of this canal, there was only one time we had a flat sea in that channel.

The Hudson River and New York Harbor

When departing the Great Lakes, the trip down the Hudson River is delightful. Pay close attention to and travel with the current. While not formidable, it will have a definite impact on your progress.

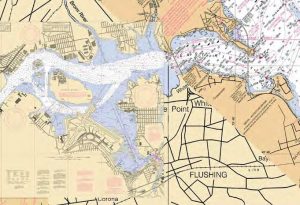

If you’re coming from Long Island Sound, refer to the current chart for New York Harbor and the inset specifically for Hell Gate and N Brother Island. It is 4.5 nm from Throg’s Neck Bridge to N Brother. If the current is more than 1 knot against you, wait. Time your arrival at N Brother for slack current before the ebb and you will have no current problems.

If you’re coming from the east down Long Island Sound, you will ultimately have to transit the notorious Hell Gate of New York Harbor. You won’t have horrific seas, but the current is formidable. Don’t go against it; you will lose. It is 4.5 miles from Throgs Neck Bridge to North Brother Island, adjacent to Hell Gate. If you can time your run to arrive at slack current before the ebb at North Brother Island, Hell Gate will be a piece of cake. Keep looking astern for commercial traffic and prepare to get out of their way.

If you arrive at the Throgs Neck Bridge and the flood current is running more than 1 knot against you, it is futile to go farther as it will only get worse. Stand off or anchor in Little Bay until the current slacks off. If it’s late in the day and you must stay overnight, directly across from Little Bay is the Harlem Yacht Club, which has the best clam chowder in the universe. Once past the tip of Manhattan, cross the Hudson River, anchor behind the Statue of Liberty at Liberty State Park, and plan your next move south.

Chesapeake Bay

When sailing south from the Northeast, don’t miss the Chesapeake Bay. It is unique. There are more gunkholes and creeks than you can explore in a lifetime. Creeks tend to silt up over time, so charted depths can sometimes be inaccurate. Strong, prolonged northerly winds tend to blow the water out of the bay, resulting in a low tide that can last for days. If you run badly aground in these conditions, you might wait a long time to float off. You can sail the creeks in almost any conditions but beware of the bay itself. It can be very nasty in strong northerly winds.

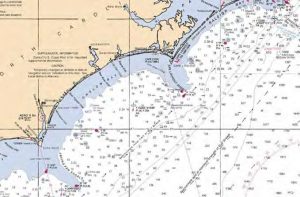

It’s easy to think that once you are south of Cape

Hatteras, you can go offshore. Remember, Cape Lookout Shoals extend 20 miles offshore and Frying Pan Shoals extend 30 miles. The Gulf Stream runs right up to these shoals. If you guess wrong with the weather you will not be happy!

To get a real feeling for the bay, I recommend two books: Chesapeake by James A. Michener is an extremely accurate dynastic novel that chronicles the history of the bay and those who settled it. Beautiful Swimmers by William W. Warner, a Pulitzer Prize winner, is specifically about the local blue crab — to understand the crab is to understand the bay.

The Intracoastal Waterway

While the cruising guides for “The Ditch” are good, there are a few things to add. The actual entry into mile 1 of the ICW is rather obscure. As you cross Norfolk Harbor you pass through Norfolk Shipbuilding & Drydock Corporation (NORSHIPCO), which will make you think you are in the wrong place as you dodge aircraft carriers, destroyers, and tankers in various stages of construction. But carry on and stay out of the way. Mile 1 is just up ahead.

As on the Chesapeake Bay, do not trust the soundings outside the channel that are on your chart. The main channel will always have adequate depth, but as you trundle on day after day, your attention may wander, and in some areas, if you drift outside a channel marker by as much as a foot, you could find yourself hard aground. What looks like an unmarked 8-foot-deep channel to a good anchor spot may only have 5 feet or less.

Going south, the red buoys will be on your starboard side. If you concentrate on staying on the starboard (red) side of the channel and steer directly from red to red, you will certainly go aground. We were advised that it is better to steer in an elongated zigzag pattern. As you pass a red buoy, look for the next green and steer toward, but not to, it, still favoring the starboard side of the channel. As you steer toward the green, when the next red becomes prominent, steer back toward, but not to, red. Red, green, red, green. Don’t overdo it and hog the channel, but the method works. Remember to always look behind you for approaching powerboats. They travel at a rather high speed and will show no mercy. AIS is a great predictor of approaching traffic.

There is very little you can do about the current on the ICW. On runs between inlets, the current will be with you, then against. What you gain you lose, and vice versa. When you pass an inlet, keep track of the buoys, know if you are sliding sideways or not, and don’t run onto a sandbar.

On an offshore passage from St. Augustine to Ft. Pierce, Florida, we were overtaken by an approaching cold front. With the Gulf Stream immediately to our left, we were trapped and had no choice but to cross the shoal water

off Cape Canaveral in 8-foot breaking seas.

The Gulf Stream

If you are taking the outside route from the Chesapeake Bay, you’re going to encounter the Gulf Stream. This river in the ocean flows north at an average speed of 3.5 knots. I have seen it as high as 6 knots. When a cold front passes and the wind blows from the north, it can result in catastrophic seas.

You might want to go offshore either to gain experience or to save time. More distance can be covered in a two-day coastal passage than you would in a week on the ICW, but be careful and pay attention to the weather. In late November we wanted to go outside from Charleston, South Carolina, and the forecast clearly said: “A cold front will pass off the Carolinas later tonight …” We read it, left anyway, and we got pasted big time! Lesson learned.

A weak front can last from a few hours to a day or more before it blows out. Without any warning, it can also develop into a depression, with storm-force winds that could last for a week or more and turn into a serious survival situation. The Gulf Stream comes closer to shore the farther south you go. In such conditions an inlet might not be passable, leaving you trapped outside. With the stream so close to shore, you have no sea room to run off, and if you heave to, you will drift into the stream, which will be a nightmare.

Dealing with the Capes

For decades, cruisers heading south have been under the impression that once south of the dreaded Cape Hatteras, they could go safely offshore at Morehead City, North Carolina, and skip the drudgery of “driving down the ditch.” That’s the theory. The reality is that many things conspire to make this potentially dangerous. Immediately outside Hatteras Inlet you run smack into the west wall of the Gulf Stream. Sixty-five miles farther south, you run into Cape Lookout and its shoals, which extend 20 miles seaward, again right up against the Gulf Stream. Eighty miles farther on are Frying Pan Shoals, which extend seaward 30 miles up against the wall of the stream. In good weather you might pull this off, but due to “Cape Effect,” the weather here is notoriously unstable. If you get caught out there, you’re in big trouble. On our first trip south we thought better of it, stayed inside and avoided a front that turned into a major winter storm. Farther south we were not so lucky.

The author and his wife, Ellen, enjoy the warmer weather down south.

In Florida, wanting to save time, we made the gigantic mistake of going outside at St. Augustine. As we approached Cape Canaveral, we found ourselves in shoal water with a front approaching. We could not get safely into deep water without running into the Gulf Stream, so we continued south with the north wind astern but just inside the stream. What we failed to understand was the effect the strong north wind would have on the shoal water off Cape Canaveral. The front passed just after midnight. As the wind howled over the shallow water, the seas built to over 8 feet and began to break regularly over the stern and over us. Within minutes we were very wet and cold. Trading places in the cockpit every 20 minutes, we watched in awe as our newly installed windvane handled the helm like someone possessed. Lesson learned once again.

You’ve Done It

With all the beauty, adventure, and obstacles of the southbound journey in your wake, you’ve become a better sailor. In the process, you have also probably learned a lot more about your boat, weather systems, tides and currents, and so much more. Now you can settle in and enjoy the warmer weather and water. Congratulations — you’ve made it south.

Good Old Boat Contributing Editor Ed Zacko, a drummer, and his wife, Ellen, a violinist, met in the orchestra pit of a Broadway musical. They built their Nor’Sea 27, Entr’acte, from a bare hull, and since 1980 have made one transpacific and four transatlantic crossings. After spending a couple of summers in southern Spain, Ed and Ellen shipped themselves and Entr’acte to Phoenix, Arizona, where they have refitted her while also keeping up a busy concert schedule in the Southwest. They recently completed their latest project, a children’s book, The Adventures of Mike the Moose: The Boys Find the World.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com