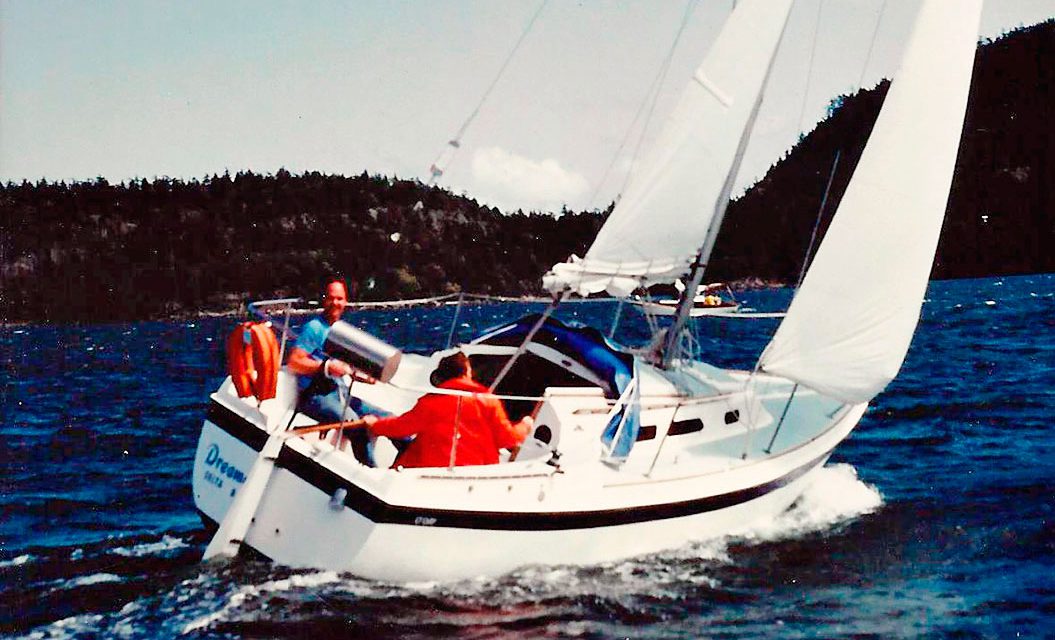

Years ago I owned an O’Day 25 on which my family and I explored the coast of British Columbia. Our travels took us from the far reaches of the Salish Sea all the way up to Desolation Sound and beyond, including the remote inlets of the west coast of Vancouver Island.

Often, when the rest of my family was otherwise engaged, I’d sail Dreamer singlehanded or invite buddies along. One such friend, Tony, had recently been hired by the police department where I worked, and we shared a watch. Over coffee I learned that he had owned a Bayfield 25 in Ontario, where he sailed Lake of the Woods—a decent-sized lake on both sides of the U.S./Canada border—with his young family before moving west. He had an irresistible urge to explore the Gulf Islands, the smaller islands in and around Vancouver Island, and was actively searching for boats to buy. In short order it was decided that Tony would join me on a spring sailing weekend to the Gulf Islands.

Sailing out of our winter moorage on the Fraser River, just south of Vancouver, we crossed the Salish Sea and enjoyed three glorious days of sunny skies and moderate winds. Each evening in the Gulf Islands saw us in a quiet anchorage devoid of the summer crowds. Tony was full of questions and observations. I got to see my usual haunts through new eyes.

Our last day in the Islands included the return passage across the Salish Sea to our summer moorage at Tsawwassen, which is near Vancouver and just north of the U.S./Canada border. The trip would begin with the transit of a narrow, dredged channel separating the Gulf Islands of Thetis and Kuper, from where we’d eventually make our way to Porlier Pass and open water beyond. One of four major passages separating the tranquil waters of the Gulf Islands from the more boisterous Salish Sea, the currents in Porlier Pass can run up to nine knots. In a five-knot boat, this had to be accounted for. We calculated distance and currents and decided on an early morning departure.

The next day we enjoyed cool, clear skies with a rising sun that was warm on our faces as I carefully powered between Thetis and Kuper Islands. Even when other experienced sailors are aboard, I tend to take the helm of boats I own when making a difficult passage. That is, if there’s any risk of something bad happening, I want to be the one driving.

After clearing the channel we powered toward another gap, this one between Hall and Reid Islands. We were now in the relatively open waters of Trincomalee Channel, and visibility was only somewhat limited by morning mist. I handed the tiller to Tony, telling him that I was going below to chart a compass course from Porlier Passage to Tsawwassen (no electronics back then!). I confirmed my intentions with Tony: We’d power between Hall and Reid Islands, then turn slightly to port and aim for Porlier Passage a mile further east. The islands were clearly visible less than a mile ahead. The detailed chart of local waters was face-up on the cockpit seat. I didn’t reference it, but simply pointed to where we had to go. I did mention that we had to make the best time possible toward the pass, since the flood tide there would soon change to ebb, and we had to get through before then. Long a lake sailor, Tony had been intrigued over the weekend by how quickly the water changed direction in the narrow passages we had already encountered. “Don’t be going on a sight-seeing expedition this morning!” I warned jokingly as I stepped below.

I had no qualms about leaving Tony at the helm; we’d been sharing that duty over the last two days, and I was comfortable with going below. And I was only a few feet away, within easy reach if a question arose. I focused on the large-scale chart and rudimentary math.

In an O’Day 25, the galley faces aft from its position against the cockpit bulkhead. The stove was to starboard next to a small sink, and the icebox lid was beneath the companionway. With the paper chart spread out on the icebox lid, I pushed a drink glass and a table knife—items that had been left unsecured in our haste to leave–out of the way to make room. I could see Tony was standing in the cockpit facing me, hands in his pockets with the tiller between his legs, calmly enjoying the spectacular scenery. I felt no need to hurry charting our course as we were still about 30 minutes from reaching Porlier Passage. We were in relatively open water. All was calm and under control.

Suddenly, a huge explosion of sound and motion shattered my world. I was face down on the cabin sole, not knowing how I got there. Tony was flailing away on top of me. I could hear the outboard screaming at full throttle on the transom. After a few frantic moments of thrashing legs and elbows I made my way up to the cockpit and shut off the outboard motor, which was tilted up on its bracket. Blissful silence. Hall Island—and it was far too close—loomed just to port. I peeked over the side of the boat. Beneath us, there was a huge green rock. Damn! How had we gotten this close!

In the cabin, Tony was examining the bilge. He reported that it was still dry. For the moment we were good . . . and we weren’t even aground. The current was slowly drifting us into deeper water. Despite the recent chaos in our little world, all was now serenely calm. The sun still shone warmly, the water was glassy smooth, and there wasn’t another boat in sight. With still-pounding hearts we sat in the cockpit and discussed what had just happened.

It was obvious that Tony had been cutting the corner. We were nowhere near the center of the gap that I had pointed out between Hall and Reid Islands. An examination of the chart showed two rocks, one that was visible about 100 feet off the end of the island, and the other lurking just below the surface soon after and slightly to seaward. Tony had not seen the submerged rock on the chart. Tony was in unfamiliar waters; I wasn’t. At a minimum, I should have reviewed the chart with him as we approached the gap. Short of that, by simply sticking my head out the companionway every now and again to keep an eye on where we were going, it’s likely we could have skirted any trouble. All that said, we were still afloat and there were no bodily injuries. It was time to determine our next step.

Further examination of the bilge confirmed that no water was coming in, and that there were no visible cracks in the fiberglass. The mast was still up, and the outboard was still attached to the stern. The trailing edge of the dodger had been pulled off its snaps and pushed forward, with just one errant snap that had been pulled out of the deck.

The inside of the cabin was a bit more chaotic. Anything that hadn’t been secured was now on the floor, and the Force 10 cabin heater, mounted low on the forward bulkhead, had a round dent in its convex front. Next to it, impaled in the teak plywood, was the table knife that I had shoved aside on the icebox lid. Shards of glass littered the sole. On the icebox lid was the heavy base of the drinking glass, with the top half of the glass missing.

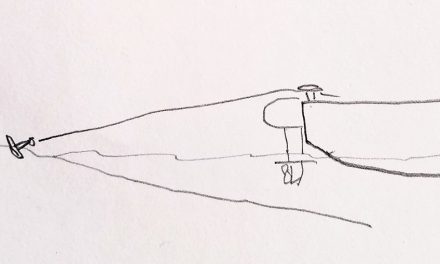

As serving police officers, and having investigated many traffic collisions over the years, we did a quick review of what had transpired. Traveling at approximately five knots, the bottom edge of Dreamer’s keel—many O’Day 25s had lifting keels, but this one had a full, lead keel–had impacted the face of the big green rock I’d seen. The sudden stop launched Tony, hands in pockets, forward into the cabin, and on his way in he struck the trailing edge of the dodger. Then, airborne all the way to the Force 10 cabin heater mounted on the forward bulkhead, he dented that with his head before landing on me. While all this was in motion my feet had been kicked out from under me and I went facedown onto the cabin sole. The table knife, which had been left on the icebox lid behind the drinking glass, had been hurled forward, taking the top of the glass off as it flew through the cabin to impale the bulkhead. The heavy glass bottom remained in place.

But how did the knife not strike me on its way to the forward bulkhead? It must have whistled over my head as I went down. All this mayhem stemming from a five-knot impact. Other than Tony having a bit of a sore head, there were no other injuries.

We lowered the outboard back into the water where it started on the first pull. Options at that point were to stay within the Gulf Islands and search for somewhere to haul-out, or to carry on home. We both had to work the next day, and the wind forecast was minimal. Home was the more appealing option. Boat speed was cautiously brought back up to five knots with no apparent vibrations from the hull or keel. The 12-mile crossing to Tsawwassen was anticlimactic.

Examination of the hull and keel after a haul-out revealed damage at the lower leading edge of the lead keel. We had struck the rock full on, tilted forward, and then skipped over. Amazingly, there were no cracks at the hull/keel joint. A strongly built little boat! Hammering the lead back into shape and applying a bit of epoxy fixed the damage without major expense. We sailed the O’Day for many years afterward without issue and managed to keep well clear of submerged rocks. Tony subsequently purchased a Columbia 26 and we both enjoyed cruising the coast of British Columbia for many more years.