New engine or rebuild? And should you install it yourself?

On a cold February day, Don studies his engine replacement information. Delphinus rests outside awaiting her new engine.

Chances are your boat is like a member of the family. You could no more dispose of it than sell your only child. But, inevitably, the day arrives when you realize that your power plant is on its last legs, and there are some important decisions to be made.

Some boatowners go to the boatyard, write a check, and say effortlessly, “Call me when it’s ready.” For most of us, however, it’s a traumatic moment. After all, repowering an inboard auxiliary sailboat is a lot more involved than simply dropping a new outboard onto the transom.

For diesel engines, the symptoms begin to develop years before things become critical. Whereas your brand-new diesel would start within the first turn, now the cranking takes longer — and, if the weather is cold, much longer.

When Rudolf Diesel first patented his engine in 1892, it was a revolutionary idea. His engine used the principle of auto-ignition of the fuel. This idea, based on the work of English scientist Robert Boyle (1627-91), was that you could ignite the fuel from the heat produced by compressing the air in the cylinder. If this compression were great enough, the temperature in the cylinder could be raised enough to ignite the fuel-and-air mixture. In modern diesel engines, this compression ratio is between 14:1 and 25:1, which raises the temperature of the air in the cylinder to well above the burning point of the diesel oil that is injected into the cylinder (about 1,000 degrees F).

Compression, then, is the key to a successfully operating diesel. But when a diesel is up in years, cylinder walls and piston rings are worn and fouled with deposits, so they no longer make a good seal. Valves and valve-seats have also become pitted and fouled and don’t seal properly. Thus, it becomes much more difficult to get the compression necessary for ignition, especially when the engine block is very cold and rapidly saps away the heat of compression.

Biting the bullet

Discussing the proposed engine replacement with Tom Dittamo of Harbor Marine Engines.

When the day finally arrives for you to bite the bullet, there are two options: get the engine rebuilt or buy a new one. If the horsepower of the old engine was perfect, if it pushed you through heavy winds and waves when they were right on the nose, and if that engine has always been freshwater-cooled and has not had other serious problems, rebuilding that old engine might be more compelling. Certainly it would be less expensive.

But if your present engine is very old and has had raw saltwater cooling, chances are that having it rebuilt will not be practical. There will be rust, frozen bolts, parts to replace, and probably great difficulty in getting those parts. Even though the cost of rebuilding an old engine is typically about half that of a new engine, you may very well be throwing money away on a rebuilding venture. And if you have always felt that you could use just a few more horsepower to get you through those nasty conditions, now is a good time to upgrade.

Remember that when you decide to go with a new engine there are many more costs involved than just the price of the engine itself. Engines today, which provide the same horsepower as your old engine, are usually lighter and smaller and rotate at higher speeds.

These smaller dimensions in width, height, and length make it almost certain that your engine bed will have to be rebuilt to accommodate the smaller engine, since its mounts will probably be closer together.

It’s also important to know the type of transmission on your new engine. Basically, there are three different types:

- Parallel is a transmission whose propeller-shaft coupler is in line with, or parallel to, the engine’s crankshaft.

- Angle-Drive is a transmission whose coupler is at a downward angle to the crankshaft.

- V-Drive is a version in which the transmission is forward of the engine and makes a V-turn to drive a propeller shaft leading aft.

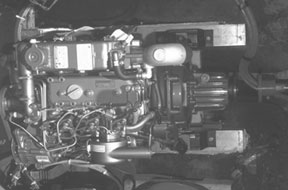

The new Yanmar 3GM30F is delivered early, which gives Don adequate time in which to measure it and familiarize himself with it.

Each of these configurations presents its own problems when rebuilding the engine bed. The smaller fore-and-aft dimensions will probably also mean that you’ll need a new and longer prop shaft unless you can set the new engine farther aft on the beds. Having a new shaft is probably a good idea anyway. After the old engine has been removed and the old shaft has been slid out of its stuffing box, you’ll probably see rings of wear in the shaft where the stuffing box (and sediment) have created grooves. If your old shaft is more than a decade old, you’ll probably find that the flange coupling is so frozen onto the shaft with rust that it’s impossible to free it without further ruining the shaft.

Also, if you didn’t previously have a flexible coupling or Drivesaver, now is a good time to add this item, which will help protect your new transmission in the event of the propeller picking up a piece of wood or a heavy line. If you’re already using a flexible coupling between the engine and the shaft, chances are that the bolt holes in this flexible coupling or Drivesaver will not match your new engine’s coupler, and a new, matching, flexible coupling will have to be purchased.

As for the propeller, there’s a 50-50 chance that the new engine may rotate in the opposite direction from the old engine. (If your present engine turns the prop shaft counterclockwise in forward gear, as seen from the stern, you now have a left-hand prop. If the new engine has a clockwise rotation, you need a new prop.)

Even if the direction of rotation of the new and old engines is the same, chances are that the engine speed, the horsepower, and the transmission gear ratio of the new engine will be different from the old. This will probably mean a new propeller of different pitch, diameter, or number of blades, making your old prop obsolete.

Free consultation

Before and after: preparations for the installation of a smaller Beta Marine engine in a C&C 30 required a new engine bed and oil drip pan to be constructed. This boat began life with an Atomic 4 which was later replaced by a Bukh and finally the Beta.

Most engine installation manuals give charts showing the recommended prop for your particular displacement and hull configuration, and most propeller manufacturers provide a free consultation service to determine the type of new prop you’ll need when repowering. Michigan Propellers, for instance, has a Pleasure Boat Prop-it-Right Analysis Form, which will suggest the correct propeller for your new engine.

On some boats, the engine and propeller shaft are deliberately installed at a slight angle off the fore-and-aft centerline of the boat. This may have been done to offset the tendency of a single engine to push the stern to one side or the other or to allow the shaft and prop to be removed without removing the rudder. If your boat has an offset driveshaft, repowering with an engine whose shaft rotates in the same direction as the old engine may be preferable. (We have an offset shaft on our C&C 30. We repowered with opposite rotation and are satisfied with the outcome. It seems like this should have mattered more than it did. —Ed.)

The smaller proportions of a new engine and the rebuilding of the engine bed will also mean that your present oil drip pan beneath the engine will no longer fit, and a new pan will have to be fabricated and installed.

There is one complication of a physically smaller engine that may be overlooked. If you’ll be using your engine to supply hot water through a heat exchanger, the water connections on the new engine might well be lower than on the previous engine. If the heat-exchanger water lines from the engine to the hot water tank slope upward, an air-lock can develop in the heat-exchanger coil in the hot water tank that will prevent water flow and, consequently, heat exchange. One way to overcome this problem is by installing an expansion tank at the highest point in the water lines at the hot water tank. The pressure cap on this tank should match that of the one on the engine, and filling the water system can be done through the filler cap of the new tank.

Fuel-return line

With diesel engines there’s another thing to consider. Some diesels had just one fuel line going from the tank to the engine. Most modern diesels, however, also require a fuel-return line from the engine to the tank (often called the overflow fuel line). Depending on an engine’s design, the amount of fuel returned to the tank via this line can vary greatly.

If you had an engine with a single fuel line, the chances are that you don’t have a fitting on top of the fuel tank(s) for this new fuel-return line. This problem can usually be solved by removing the current air-vent fitting at the top of the fuel tank and substituting a T-fitting. One side of this T can then still be used for the air vent while the other side can be used for the fuel-return line. This problem also will be encountered when changing from a gasoline engine to diesel.

It’s also likely that with a new engine, the water, fuel, and exhaust systems may have to be rebuilt or re-sized. Even if this isn’t the case, when the old engine is removed is a good time to replace those old hoses.

If you are considering selling your boat within the next few years, it might be tempting to believe the value will increase enough to offset the money you have put into a new engine and its installation. But although a boat will be worth more with a new engine, the increase in value will probably not equal your investment when you sell your boat. The same caveat is true if you convert from gas to diesel. But here we are discussing repowering your boat because you want to use it for many more years, not with the idea of selling it.

Do it yourself?

Most owners will hand over the repowering project to a knowledgeable, qualified, and reputable installer. Still, it’s valuable to know the potential problems along the way. If you have decided to have the job done professionally, there are several preliminary steps to take:

- Only accept bids from installers who have actually examined your boat.

- Consider the reputation of the installer and the yard.

- Ask whether they have installed this type of engine before.

- Ask for references from owners of boats similar to yours who have had the same job done.

- Make sure that all associated work is specified on the proposal.

- Be sure that the final installation will conform to American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) standards.

Some boatowners will want to tackle the job themselves. If you do your own installation, there are much greater benefits than saving money. You will end up with an intimate knowledge of your new installation. This, alone, is a great incentive.

If you decide to do the job yourself, it’s still a good idea to have a professional in your corner, someone who is a dealer for your new engine or who has done engine installations, and whom you can trust, talk to, and order parts from. If you’re doing your own work, the closer the yard is to your home, the better. And if you don’t want to tackle the whole job yourself, you may elect to do just the engine rewiring, the exhaust system, the water system, or the fuel system, after the new engine has been installed on its bed and aligned.

Whether you do it yourself or have the engine installed by a professional, the job requires engineering judgment and good mechanical skills.

We were fortunate that for years there was an engine mechanic near us who would give us excellent and detailed advice whenever we had a do-it-yourself engine job to tackle. Tom Dittamo, owner of Harbor Marine Engines, in Lanoka Harbor, N.J., has his business in a marina less than 15 minutes from our home. Tom is also a Yanmar dealer, so we chose that yard, Laurel Harbor Marina, in Lanoka Harbor, for our haulout and engine replacement.

We bought our new engine from Tom six months before beginning our project. He stored it in his shop at the marina during this time, which allowed me to go in for all the necessary measurements whenever I needed to. This enabled us to plan well ahead for our project and purchase all the ancillary gear necessary. (This early engine purchase, which was suggested by Tom, also saved us 5 percent on the manufacturer’s price increase that went into effect shortly after we ordered the engine).

Start early

Replacing an engine often means replacing the propeller as well. The C&C 30 gets a new right-hand Michigan Wheel 15 x 9 2-blade propeller. Later this was replaced by an Autoprop.

Changing inboard engines is not a simple project. If you are very adept at major projects, if you are a good mechanic, if you have lots of time and patience, and most of all if you enjoy working on boats and this type of challenge, then you should start doing your homework and putting together a loose-leaf notebook.

Begin buying the necessary parts months in advance. I started buying my conversion gear six months before the start of my project, and that was not too soon. I discovered that the delivery of a new prop would take six weeks and the longer prop shaft would take almost as long, even though it was always: “I’ll have it for you next week.”

It’s important to learn as much about your new engine as possible before you start the project. There are many engine distributors who offer one- or two-day seminars specifically targeted at owners of auxiliary engines. Mack Boring & Parts Company, which sells Yanmar engines and parts, has one- and two-day owner seminars on Yanmar engines that are invaluable. These classes are given at Mack Boring locations in Union, N.J., Wilmington, N.C., Middleborough, Mass., and Buffalo Grove, Ill. The classes cover the theory of operation, explain all the parts of your new engine, cover routine maintenance, and include a hands-on session that gives participants the opportunity to do routine maintenance on the engine they will actually own, including adjusting and bleeding it.

Incidentally, one item that is invaluable in setting up the placement of a new engine on the rebuilt bed is an engine jig, which can usually be rented from the engine distributor. The jig consists of light-weight metal framework that locates the proper position of the engine mounts and shaft alignment. It copies the exact size and angle of the real engine and can be aligned with the prop-shaft coupling, revealing whether there has to be any change made in the engine bed or mounts long before the engine is swung into position.

The alternative to the engine jig uses another type of alignment method that will be discussed further in Part 2 of this series, which will run in the November/December issue of Good Old Boat.

Installation manuals

Nearly all engine manufacturers have comprehensive installation manuals that are essential for the do-it-yourselfer. These manuals, which should be part of your repowering notebook, have step-by-step installation instructions, including alignment procedure; wiring diagrams; engine specifications, dimensions, shaft and prop recommendations; and fuel, water, and exhaust-hose requirements. It’s also a good idea to purchase a service manual for your engine. It will be a handy reference for the future, and it gives some installation information that isn’t necessarily shown in the installation manual.

New engines come with their own instrument panels. If you have an instrument panel recess in your cockpit, especially one that is molded into a fiberglass boat, make sure that the new engine’s instrument panel will fit into the old recess. If it won’t, it might be tempting to try to use the old panel with the new engine, but this usually is asking for a lot of headaches, including replacing the tachometer, oil and temperature gauges, and wiring. Some manufacturers have several panel options of different sizes. Yanmar, in their GM series for auxiliaries, have three control panels of varying sizes and options.

Repowering a boat from a gasoline engine to diesel power needs extra consideration. Diesel engines of equivalent horsepower are usually physically larger than their gasoline counterparts. You may find, however, that the Atomic 4 in your boat has much more horsepower than the diesel you will replace it with. Many smaller boats were powered with an A4 and a direct-drive transmission. Only half the engine speed range, and thus roughly half the horsepower, was used. These direct-drive boats were equipped with very small props.

Bed modification

Out with the old (Volvo)

Even if you’re sure an appropriate diesel will fit in the engine compartment, you’ll probably need to rebuild or modify the engine bed. Consider the maximum-diameter prop that can be fitted to your boat and still have the required tip clearance. Match this against the prop that the new engine will need. Not all gasoline tanks and fuel lines are compatible with diesel fuel and, as mentioned previously, a fuel-return line will also have to be added. The primary water-separator/ fuel filter will also need to be replaced. In some cases, the prop shaft may have to be increased in size which, in turn, means a new stuffing box.

In with the new (Yanmar)

Most of us have a pretty good idea how much power we need, based on the performance of our previous engine. The old rule-of-thumb for auxiliaries of 2 hp for every 1,000 pounds of displacement is usually pretty good. If you really want to get into the calculations, then consult Dave Gerr’s Propeller Handbook or Francis Kinney’s Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design. Another source of information is at http://www.boat diesel.com on the web. This site, which provides a wealth of information on diesels, charges a $25 membership fee. If you click on Propeller/Power/ Shaft Calculations, you can find the proper shaft size, the power required for a given hull, and the recommended propeller specifications.

Be sure to check the alternator options available for your new engine. If your electrical consumption is high, as is the case with a refrigeration system or a watermaker, be sure to specify the appropriate alternator when you order the new power plant.

Engines for an auxiliary must, above all else, be reliable. When selecting the manufacturer of your new engine, do your homework. Talk to other sailors who have had an engine replacement recently and get their opinions. Get information from various engine companies and local marine mechanics, check out these engines at boat shows, and talk to the manufacturers’ reps.

When you’re finally back in the water with a new engine, you’ll feel much more inclined to take that long cruise you’ve been delaying for years, safe in the knowledge that you have a new power plant of high reliability for which parts are readily available.

Article taken from Good Old Boat magazine: Volume 5, Number 5, September/October 2002.

Part 2 of Don’s repowering series, with a focus on installation, will appear in the November/December 2002 issue of Good Old Boat.

American Boat and Yacht Council (ABYC) 410-956-1050 http://www.abycinc.org

Beta Marine 252-249-2473

Harbor Marine Engines Laurel Harbor Marina 609-971-5797

Mack Boring 908-964-0700 http://www.mackboring.com

Michigan Wheel Corporation 616-452-6941 http://www.miwheel.com

Perkins-Sabre 253-854-0505

Vetus 410-712-0740 https://www.vetus.com

Volvo Penta of the Americas Inc. 757-436-2800 https://www.volvopenta.com/en-us/

Westerbeke Corporation / Universal 508-823-7677 http://www.westerbeke.com

Yanmar America Corp. 847-541-1900 http://www.yanmar.com

Propeller Handbook, by Dave Gerr Ask BookMark 763-420-8923