The rig Americans made their own is still “scooning” after 300 years

The rig Americans made their own is still “scooning” after 300 years

It’s not discreet to say this, but I’ve been having an affair, and I’m not ashamed to admit it. It’s been a lifetime love affair with schooners. There are still some, and I suspect many, of us who believe that no sailboat ever built can compare in beauty with the schooner. But why are people still drawn to this rig when the schooner as a recreational boat has all but faded into oblivion? I think it’s because the schooner rig has a symmetrical rightness about it. With a gollywobbler, fore gaff topsail, spinnoa, flying jib, forestaysail, fisherman – what other rig can carry such a mixed bag of sails and (instead of looking ridiculous) become breathtaking?

From the deck, as you look above, a cloud of white is overhead – but aesthetics aside, no other cruising rig has more flexibility than the schooner. It can be adjusted to suit almost any condition of wind or sea. OK, so it doesn’t go to windward quite as well as that high-aspect-ratio racing sloop, a characteristic common to all split rigs, but if you’re searching for a love affair – if, as you sail by, you appreciate it when people turn to look and take pictures – then maybe, just maybe, you too are a schooner nut. If you are, you’re in good company, since to judge by their designs and writings, John Alden, Uffa Fox, and Joseph Conrad were also schooner enthusiasts. In Mirror of the Sea, Conrad rhapsodized: “They are birds of the sea, whose swimming is like flying . . . the manifestation of a living creature’s quick wit and graceful precision.”

From Holland

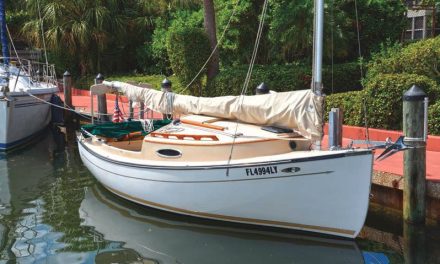

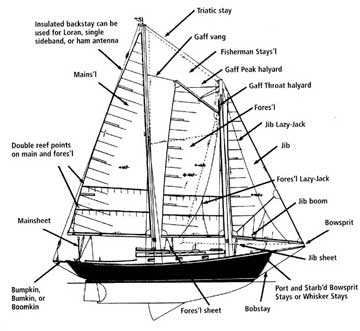

Don Launer’s Lazy Jack 32 designed by Ted Brewer, above, and flying its fisherman staysail, at left. This sail is hoisted by halyards on the foremast and mainmast. The sheets are led to aft turning blocks and forward to cleats. It is tended like a jib when tacking.

Although most people consider the schooner to be as American as apple pie, the popular idea that it originated in New England is probably incorrect. It seems likely that they were developed in Holland in the early part of the 17th century as they are depicted in paintings of that period. There’s no doubt, however, that Americans adopted the schooner as their own. The American coastal schooners were not deliberately designed to look beautiful, they were designed as vehicles of commerce with good carrying capacity, able to haul lumber, fish, coal, ice, stone, bricks, fertilizer, and the like, in all possible weather and at good speed. Thus a perfection of hull form was developed, and something completely functional as well as aesthetically beautiful was the result.

They were as vital to American commerce as are the highways, railroads, and airlines of today. In those days before railroads, when overland routes were not much more than muddy paths in the warm months and snow-covered ruts during the winter, schooners moved people and supplies between the coastal cities.

Waterborne commerce along the East Coast of the United States was a natural result of its topography. Our eastern shoreline is replete with estuaries, rivers, bays, and sounds, which allowed the windward ability of the schooner to carry them far inland where square-riggers dared not venture. By the late 18th century, the schooner had become the national sailboat of the United States and replaced the square-rigger as the ship of choice for coastal commerce.

Camden’s schooners

On the interior, Don fiberglassed vertical furring strips 16 inches apart. He glued foil-covered polyurethane insulation between the furring strips and placed mahogany planks on top. This insulation sandwich prevents hull sweating, makes the cabin easier to heat and cool, and acts as a radar reflector.

During the schooners’ heyday, boatbuilders all up and down the coast were trying to keep up with the demand and turning out large coastal schooners in record numbers. The small town of Camden, Maine, alone sent more than 200 down the ways, and schooners can still be seen in Camden’s harbor.

Even though the coastal schooner was a boon to commerce, by today’s standards, travel in those days was still primitive. A trip from New York to Philadelphia, which now takes about two hours by car, would take two days by coastal schooner if the wind was exactly right, or it could take two weeks under adverse conditions. And there was always the possibility of never arriving at all if a nor’easter reared up offshore.

But what constitutes this rig that transformed the early days of our nation? The schooner is characterized by fore-and-aft sails, set on two or more masts, the foremast(s) being equal in height to, or shorter than, the mainmast, which is the farthest aft. Some early schooners were rigged with square topsails on the forward mast and were known as topsail schooners.

But what constitutes this rig that transformed the early days of our nation? The schooner is characterized by fore-and-aft sails, set on two or more masts, the foremast(s) being equal in height to, or shorter than, the mainmast, which is the farthest aft. Some early schooners were rigged with square topsails on the forward mast and were known as topsail schooners.

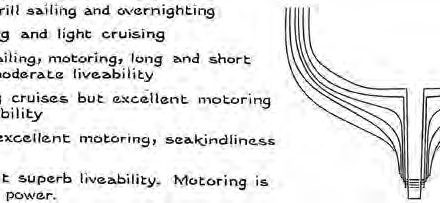

The schooner rig has three basic types of sailplans: The old-time gaff main and gaff foresail, the Marconi main and gaff foresail (which allows a permanent backstay on the mainmast, by use of a boomkin), and the Marconi main with a staysail in place of the foresail. The fishing schooners of the 19th and early 20th centuries usually carried three headsails: jib, jib staysail, and jib topsail, but most small schooners of today opt for a single headsail for ease in handling. When this headsail is on a boom it doesn’t even have to be tended when coming about. (See the club-footed jib article in the November 2000 issue of Good Old Boat).

Seldom seen today

The gollywobbler is the schooner’s version of a spinnaker. It’s a huge staysail, usually bigger than the mainsail and foresail combined, and is set in place of them for downwind running. It does, however, require a large crew to handle it and is seldom seen today. The fisherman staysail, still frequently used on even the smallest of schooners, is a trapezoidal sail, hoisted by halyards to the tops of the mainmast and foremast. Although seemingly archaic, it’s even more efficient than a genoa when going to windward, according to designer Ted Brewer.

The flexibility of the schooner rig to meet a variety of conditions is its greatest asset. When the wind starts to blow a gale, the schooner can begin by dropping one of its auxiliary sails, such as the fisherman. This can be followed by putting in reefs in the mainsail and/or foresail. Higher winds can be countered by dropping the foresail and maintaining a balance under jib and mainsail alone. Under really severe conditions, the schooner can continue under double-reefed foresail alone, or heave to under foresail. The feeling of proceeding under reefed foresail or heaving to under reefed foresail was so confidence-inspiring that when weathering a storm out on the Grand Banks under reefed foresail the Gloucester fishermen called it being “in foresail harbor.

“When a modern-day sailor first goes aboard a schooner, it is daunting to say the least – there seem to be lines everywhere. On our modest-sized schooner, the running rigging, proceeding from bow to stern, consists of: jib halyard, jib downhaul, jib sheet, jib-boom lazyjacks, fisherman-staysail halyard (and, when hoisted, the fisherman staysail tack downhaul), gaff foresail throat halyard, gaff foresail peak halyard, foresail boom vang, foresail gaff vang, foresail lazy-jacks, fisherman staysail peak halyard (and, when hoisted, the fisherman port and starboard sheets), main boom topping lift, main halyard, main-boom vang, mast-top flag halyard, spreader flag halyard, main lazyjacks and mainsheet.

Easier than a sloop

This is an intimidating array for the newcomer on board, but those lines are there to make the job easier, and once you “learn the ropes” sailing a schooner short-handed or single-handed can be easier than sailing a sloop of comparable sail area, since, with this split rig, each of the sails is smaller and easier to manage. I singlehand my schooner most of the time, even when there are guests aboard and find it easier to sail than a sloop of comparable size.

Unfortunately, anyone looking for a schooner today has limited choices. In the used-boat market there are always some wooden hulls available, and occasionally ones of steel or aluminum, but fiberglass-hulled schooners are harder to come by. For about 25 years, the Lazy Jack 32 was available to the small-boat sailor. This schooner, designed by Ted Brewer and made in fiberglass by Ted Hermann Boats, of Southold, N.Y., is 32 feet on deck and 39 feet overall, including the bowsprit and boomkin. It was available as either a bare hull, kit, or completed boat, but in 1987, with Ted Hermann’s retirement, production ceased.

One of the few fiberglass schooners now being produced is the Cherubini 48. Cherubini has been building its semi-custom 48-foot schooner for decades in a plant in New Jersey. This is a gorgeous boat, built with Cherubini’s renowned craftsmanship. It has traditional lines, a saucy sheer, tumblehome, and varnished teak, along with the beautiful schooner sailplan. The company is now known as the Independence Cherubini Co. They manufacture both trawlers and sailboats. This is the only company I know of now building fiberglass schooners.

Bare fiberglass hull

A little more than 20 years ago, the lodestone force of the schooner finally became irresistible, and we bought one of Ted Hermann’s 32-foot fiberglass bare hulls right out of the mold, doing the building and fitting-out ourselves on a spare-time basis. This consisted of fastening the deck mold to the hull mold, installing the engine, fuel system, exhaust system, and installing the masts, standing and running rigging, water system, head, electric wiring and electronics, stove, cabin heat, cabin insulation, and interior woodwork. Our schooner, Delphinus, is still our pride and joy. It turned out just as we hoped and has been a family member for two decades now.

I don’t advocate the schooner design for everyone, but for us it has been perfect. Since we are now in our 70s, ease of single-handing our boat is a prime requisite. Except for when the fisherman-staysail is flying, tacking requires no more work than turning the wheel and watching, as first the club-footed jib, then the foresail, and finally the main, move over to the new tack.

Another peripheral advantage of our schooner rig is evident when anchoring under sail. We can approach a crowded anchorage with everything up, select our spot, come up into the wind and sheet the mainsail in tight amidships. Since the mainsail is so far aft, this keeps us neatly weather-vaned into the wind while we leisurely drop the jib and lower the anchor as we begin to fall back. Then the fisherman, foresail, and finally the mainsail can be dropped in a relaxed manner while at anchor.

Traditional lines

We feel quite content with our cruising schooner. We have an able, comfortable and manageable boat with the beautiful and traditional lines of the schooner era, but our boat is ours in more than the ordinary sense of ownership. It is ours because built into it are small parts of ourselves; the planning, work, sweat, skinned knuckles, and bruised knees, along with our love of the schooner rig. All are hidden in the dark crevices of the hull, as much a part of our schooner as the bowsprit and boomkin. Possession like that is hard to come by; it can’t be bought, it must be earned.

In choosing a sailboat, its ultimate windward ability is not the only thing to consider. The owners must also take pride in their craft. Beauty and practicality can coexist. In our advanced years, it’s satisfying to know that there are some things that do improve with age: old wine to drink, old friends to talk to, old authors to read, and old sailboat designs to admire and enjoy.

More on schooners http://www.schoonerman.com and http://www.seadragon.com

This article first appeared in Good Old Boat magazine, January/February 2001.